William “Bill” P. Ramey III was being dressed down by a very unhappy judge, and attorneys who came to see him squirm were enjoying it.

US Magistrate Judge Peter Kang, threatening bar disciplinary referrals, had ordered Ramey to his San Francisco courtroom in September to explain why his Houston-based law firm handled patent infringement lawsuits in California for seven years without being licensed to practice there.

Even as he told the judge he’d practiced intellectual property law for years, he fumbled through books and papers, stammered, and struggled to cite relevant case law and attorney conduct rules. Kang pressed for answers. “I don’t see any way you can kind of stumble accidentally into practicing law,” he said.

Attorneys who’ve locked horns with Ramey, and came to Kang’s court to see how he’d react to being lectured by a judge, looked on in curiosity. Court employees and other observers snickered.

“You’ve been aware of the court’s local rules since 2017, right?” Kang asked.

Kang went on. Did you conduct a pre-suit investigation before filing? Why did you think your client can sue someone multiple times over the same patent?

“I knew the law,” Ramey said. “And then later, and when we, when this court, brought it up, we researched it again.”

''You’re always free to take the California bar exam,” Kang said.

Ramey LLP is among the most prolific filers of patent infringement lawsuits—about 260 in 2024 across the country. His five-lawyer firm handled at least 25% of patent suits filed in 2024 in the US District Court for the Western District of Texas, one of the busiest US patent courts.

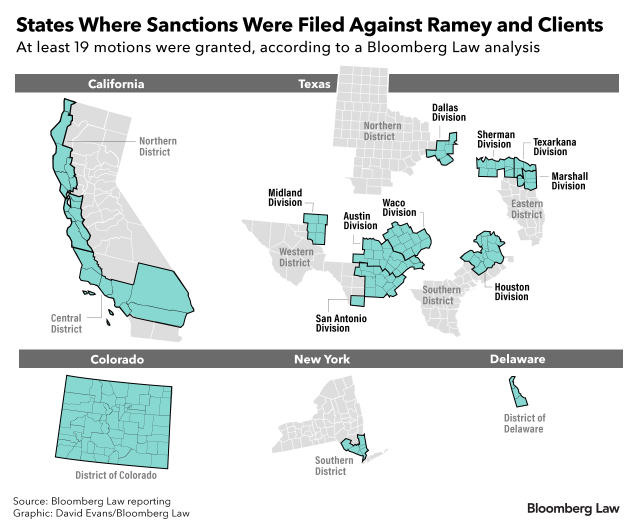

Along the way, he’s been admonished by judges for filing frivolous lawsuits and motions, submitting sloppy documents, missing court appearances, and violating court and attorney conduct rules. Judges have granted, fully or partially, at least 19 requests for sanctions and attorney’s fees against Ramey, his firm and/or clients, totaling about $2 million, according to a Bloomberg Law analysis. While facing criminal charges of attempted sexual assault, Ramey answered “no” to a question on a Covid-era Paycheck Protection Program application asking whether the firm’s owner was “subject to an indictment, criminal information, arraignment” or other proceeding.

Despite the sanctions history and a judge’s ruling that he was deceptive on the PPP application, Ramey has never faced action from a state bar, federal court disciplinary committees, or the US Patent and Trademark Office. The criminal charges were dropped after lingering for two years, and a related civil suit was settled. The PPP loan led to years of litigation, which Ramey lost, but he’s faced no further action.

“He’s a cat. He’s got nine lives,” said Jonathan Stroud, general counsel for the advocacy group Unified Patents LLC, which has challenged patents owned by the firm’s clients.

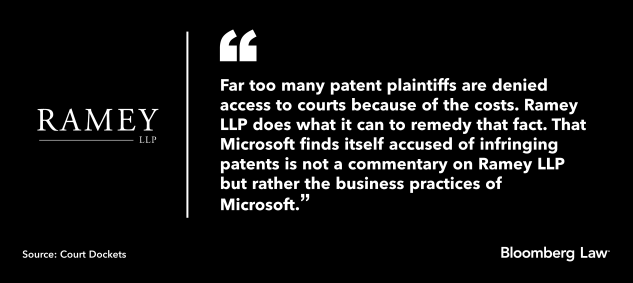

In a video interview with Bloomberg Law, Ramey described his practice as a “crusade” against corporations willing to do anything to stop patent plaintiffs of modest means.

“We wear it with a badge of honor,” Ramey said. “We’re doing everything we can. And we’ll get up tomorrow and stand up again.”

In a Feb. 11 blog post, he lashed out at tech companies, bloggers and attorneys for allegedly conspiring on “hit pieces” and personal attacks against him and even his wife. Part of the strategy, he wrote, is to label attorneys like him as extortionists. Ramey told Bloomberg Law in an email he was referring to

Upbringing, Early Career

The son of an Air Force veteran, Ramey moved to Bedford, Texas, as a youth and graduated from his parents’ alma mater, Texas A&M University, in 1995 with a degree in chemistry. He was in the school’s Corps of Cadets military-style program.

While working at industrial-gas distributor Air Liquide SA, Ramey said he frequently saw emails referring to patents and remembered a Texas A&M professor urging him to consider law. He enrolled in night classes at the South Texas College of Law Houston, graduating in 2000, according to his profile on the State Bar of Texas website.

After several career moves, Ramey returned to Houston as co-chair of the life sciences practice at what was then Novak Druce & Quigg LLP before he and colleague Matt Browning broke off on their own in 2011. They were later joined by Melissa Schwaller, who would end up succeeding Browning as a named partner.

The new firm didn’t start out as a volume producer of patent suits. That changed in 2015, not long after Browning left, when it began representing Australia-based Global Equity Management (SA) Pty., whose owners met Ramey through a mutual friend. After years of filing less than 10 patent suits annually for clients, Ramey filed more than 30 in 2016 alone on behalf of Global Equity, which owns computer operating-system patents. Global Equity officials couldn’t be reached for comment.

Many of his clients now are patent owners who don’t use them in their businesses—known as non-practicing entities or, to their detractors, patent trolls.

New Mexico inventor/attorney Luis Ortiz, a Ramey client, calls patent litigation a “David and Goliath” battle and said there’s a need for contingency-based firms like Ramey’s.

“So to even have a guy like Bill that’s willing to look at the smaller clients and their problem and help them through it to assert the IP is a big deal,” Ortiz said.

‘Recipe for Mistakes’

Ramey was dogged by accusations of doing shoddy work and flouting rules almost from the firm’s inception.

The firm “publicly prides itself on filing extraordinary amount of patent infringement lawsuits while employing very few attorneys—a recipe for mistakes and corner-cutting,” dating app companies eHarmony Inc. and The Meet Group Inc. contended in a 2023 court filing.

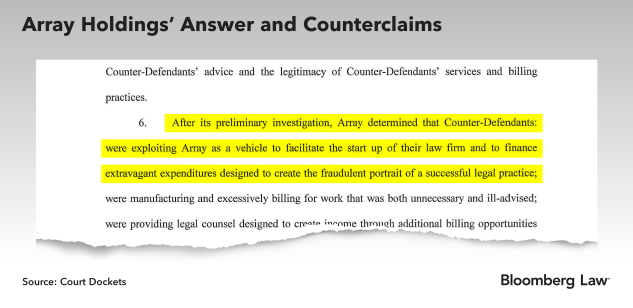

One early client, oil and gas machinery company Array Holdings Inc., described witnessing Ramey’s “gross ineptitude” during a settlement conference. The allegations in Ramey client Traxcell Technologies LLC ‘s lawsuit against

In September 2022, Chief Judge Colm Connolly for the US District Court for the District of Delaware demanded to know why Ramey didn’t comply with his order to show up for a hearing. The judge noticed that after his order went out, Ramey requested an in-person hearing for the following day in a different case before Judge Alan Albright of the Western District of Texas in Waco —1,500 miles away.

Ramey said that from reading Connolly’s order “it was not appreciated that the hearing was in person.”

“The order literally says that you are to appear,” Connolly shot back. “I don’t know how you don’t appreciate that.”

“I know for a fact Judge Albright would never have required you to appear September 2nd,” Connolly stated, according to the transcript. “I know that because I spoke with him.”

Albright and his staff didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Connolly said Ramey’s no-show “has to be sanctioned in some form.” An order is still pending.

It wasn’t the only time Ramey or his associates have failed to show up for hearings. In the Western District of Texas, the Ramey firm missed two of four scheduled hearings in a case involving

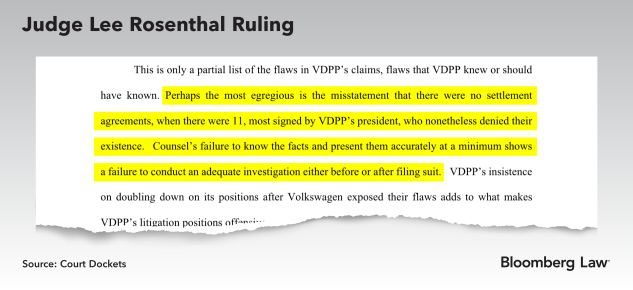

Ramey and his firm sued without adequately investigating whether clients were properly asserting patent allegations, if the accused product pre-dated the protected invention, or if clients had the right to sue, according to at least 30 defendants’ motions and judges’ orders combined.

Albright verbally awarded attorney’s fees to Blackberry after the company contended that Ramey and his client submitted allegedly forged patent ownership documents. The law firm argued it corrected “deficiencies” after a pre-filing investigation into the patent’s ownership. The written order is pending.

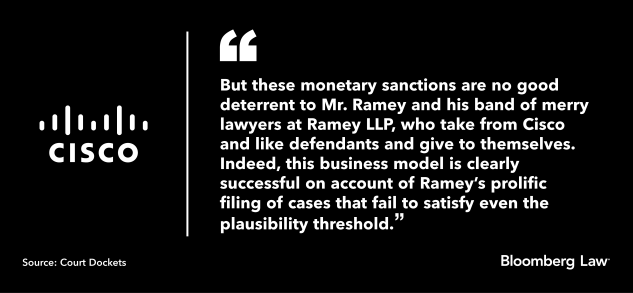

Cisco, after tangling with Ramey numerous times, asked Albright in October 2023 to block Ramey and his law firm from filing any more lawsuits against Cisco without advance clearance from the court. Its request is still pending.

Sanctions “are no good deterrent to Mr. Ramey and his band of merry lawyers at Ramey LLP, who take from Cisco and like defendants and give to themselves,” the company’s attorneys wrote. “Indeed, this business model is clearly successful on account of Ramey’s prolific filing of cases that fail to satisfy even the plausibility threshold.”

Business Model

Part of that model, opponents contend, is filing repetitive lawsuits for different corporate entities against the same defendants. Google, in one court filing, contended that Ramey clients, including entities affiliated with patent monetization firm Dynamic IP Deals LLC , also known as Dyna IP Deals, and its president Carlos Gorrichategui, had sued it more than 30 times in just over a year. EscapeX IP LLC, a Ramey client managed by Dyna IP Deals, argued prior litigation was irrelevant and Google’s allegations were “baseless.”

“Filing these sort of meritless lawsuits benefits no one, hurts innovation, and wastes the judiciary’s time,” José Castañeda, Google’s spokesperson, said in an email.

Ramey said the firm takes pleasure in being “one of the more prolific NPE firms.” “We’re very fortunate that we’re able to settle out for the clients earlier and be able to monetize IP,” Ramey said in the interview.

Microsoft alleged in a June 2024 filing that one of Ramey’s own attorneys said the financial arrangements for their cases are “leaving nothing for the client itself.” Ramey himself told Chief Judge Connolly in 2022 that its model is to cover its litigation costs with settlements or other types of recovery by patent monetization companies.

Opponents say that helps explain why Ramey files in volume and rarely pursues cases beyond their initial stages.

Two attorneys who have opposed Ramey say he can be friendly, even likable, in the initial stages of cases. He “comes across as a common sense good ole boy,” one of them said.

The behavior can change, they said, when a case reaches the discovery phase or when he is otherwise challenged. They and other legal professionals familiar with Ramey’s litigation tactics asked not to be named, citing fear of retaliation against them or their clients, or declined to comment.

Opposing attorneys have complained to judges about being subjected to verbal and emailed abuse. In one July 2022 meeting over a patent dispute involving a Ramey client and VMware Inc., “Mr. Ramey responded with an expletive-filled tirade accusing VMware of ‘threatening him,” an attorney representing the company told a judge.

Ramey, in an email, the firm disagrees with the “characterizations” of his conduct and said opposing counsel make accusations to further their cases.

Fighting Sanctions

During the September hearing in Kang’s court, Ramey said his firm didn’t seek permission to practice in certain courts if the plaintiff was managed by Gorrichategui, in order to save money for the client. Gorrichategui said in an email that Dyna IP helps around 50 patent owners enforce their rights and another 50 with brokering and marketing services.

Ramey promised the practice would stop.

“We weren’t trying to misrepresent anything,” Ramey told Kang.

His firm has received notices about not having permission to practice in the Middle District of North Carolina and the Northern District of Georgia, as well as in California, according to a Bloomberg Law analysis of court records. A judge in the Southern District of New York is considering Google’s $124,000 sanction bid that argues Ramey didn’t request permission to practice in that court.

Ramey told Bloomberg Law that the firm works to change its practices if a judge says it needs to act differently.

“We really respect the court system because there’s no other way to do it,” Ramey said.

But records show that Ramey and his clients frequently fight court-ordered sanctions and attorney fees, going as far as to call orders “void.”

‘Classic Bad Faith’

When Traxcell was ordered in March 2022 to pay attorneys’ fees to

Verizon then won a Texas state court order to stop the sale and place the patents in receivership. A judge dismissed Traxcell’s bankruptcy, calling it a “classic bad faith” move and saying that Ramey, Traxcell’s largest creditor at the time, “has a vested interest in continuing that litigation at all costs and regardless of the risks to other creditors.”

Traxcell then sued Verizon again, unsuccessfully, in federal court to void the original award—which remains unpaid. The receivership order is under appeal before the Supreme Court of Texas.

Ramey, in the interview, characterized sanctions as part of companies’ strategy to increase litigation costs and set the bar as high as possible for what an inventor must do to bring a case to court.

Defendant companies “just have a lot more money, they’ve got a lot more power,” Mark “Jeff” Reed, Traxcell ‘s owner, said in an interview. “They’ve got endless resources.”

Gorrichategui told Bloomberg Law in an interview that some inventors are scared off by sanctions.

“If you are an inventor in the US, you have two options: to assert your patent or die,” he said.

Ramey’s strategy of contesting sanctions is effective, Stroud said, because most defendants conclude the expense of fighting through appeals is more than amounts they’re trying to collect and it won’t lead to bar discipline.

“He’s financially incentivized to not look into his complaints, to file cases against the wrong party, to be sloppy, because he’s making more money doing that than being sanctioned,” Stroud, the patent advocate, said.

Sexual Assault Charge

Paralegal Elizabeth Williams followed Ramey and Browning when they broke away from Novak Druce. She became, in Ramey’s words, his right hand.

But the friendship took a turn in September 2018 that would occupy courts and lawyers for almost five years and threaten to end Ramey’s career.

As an evening work session turned to stories about childhood traumas, Williams alleged, Ramey exposed himself, pinned her to a chair and tried to force her to perform oral sex. She later told police she blacked out and woke up on the restroom floor at 1:15 a.m. with a bloody face, bruises, and second-degree burns.

“I have never heard of him acting violent like this,” Williams told police. “I trusted him.”

Ramey’s recollection was different. In a counterclaim to a civil lawsuit by Williams, he said they were both “inebriated,” that he fell asleep, and that he woke up two hours later to find Williams lying in the hallway. He alleged her injuries were caused by a fall, though Williams produced a text message from two days after the incident in which Ramey asked, “What happened. I have no memory.”

Police charged Ramey with attempted sexual assault about a year later, according to court records. The arrest was reported in the media, and the damage was immediate.

The University of Texas System and the University of Houston took their patent matters elsewhere, according to a letter and emails submitted as court exhibits. Ramey in court papers blamed Williams, though he told Bloomberg Law that the university clients didn’t fit the firm’s evolving business model.

“It did not help that I was falsely accused,” Ramey said in an email.

PPP Loan

Ramey’s arraignment was reset twice, then Covid-19 caused more delays. Then, with the criminal case still active, Ramey applied for a PPP loan in April 2020, checking “no” to the criminal history question, according to a court exhibit.

The firm, which listed 14 employees and $3.6 million in annual revenue, was approved for a loan of about $250,000 to help cover payroll and rent at the height of the Covid-19 shutdown.

Three months later, Ramey separately applied for a home equity line of credit. His bank discovered the criminal charge in a background check. Contending Ramey had lied on the application and was ineligible for PPP assistance, the bank froze the firm’s accounts—though by that point the loan money had been spent.

Ramey’s firm sued, arguing he didn’t lie because he hadn’t been indicted and therefore hadn’t been formally charged with a felony. Judge Vanessa Gilmore ruled for the bank, noting that dates for an arraignment were scheduled at the time of the application. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the ruling in June 2023, and the Supreme Court declined to hear Ramey’s appeal.

More than 160 people were criminally charged with PPP loan fraud from May 2020 through December 2021, according to a Justice Department report, but Ramey wasn’t.

Finally, more than two years after he was charged, a Harris County grand jury declined to indict Ramey, and prosecutors dropped the charges.

“This is a victory for the real victims of sexual assault struggling to find justice in the legal system,” Ramey said in a press release. Williams and her attorneys didn’t respond to requests for an interview. Officials in the district attorney’s office declined to discuss the case.

Schwaller then left the firm, leaving Ramey as the sole named partner. She had confided that Ramey sexually harassed her, Williams said in a filing in her civil case, though Schwaller filed a legal declaration backing Ramey’s statements that Williams talked about sexual misconduct allegations against then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and expressed hopes of retiring early.

Ramey said he considered Schwaller’s departure a “private business matter” but losing her was “really hard.” Schwaller, now a senior patent attorney at Hogan Lovells, didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

Williams and Ramey settled her civil lawsuit in April 2023.

Clear With Bar

Ramey hasn’t faced a public formal disciplinary proceeding from a state bar.

Ramey won’t say whether he is being, or ever has been, investigated by the bar, though in his latest blog post, he said part of Big Tech’s strategy against people like him is “complaints are filed at bar associations.” The PTO and State Bar of Texas declined to say if they have received complaints.

Given how many Texas judges have sanctioned or issued fee awards against Ramey, “it’s unbelievable that Texas has not openly admonished him or warned him or sanctioned him,” Stroud said.

Ramey’s loyal clients, like Andy Ling of AML IP LLC, say they remain confident in him.

“Patent rights are property rights,” said Ling, who is also an attorney. “All we’re simply trying to do is just assert our own property rights because there’s nowhere else to go.”

Ramey said a plaintiff-side patent attorney needs “thick skin” because big corporations are going to attack.

“It makes no sense to me that these big companies can say that we clog up the court system and that we prevent things from moving forward and raise everyone’s costs by filing one of these lawsuits,” Ramey said. “These lawsuits protect people’s rights.”

To contact the reporter on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.