- More than 20 bills introduced among at least 12 states

- Fears, farm damage vie with waste control practicalities

The stench from the sewage sludge Bob Guenther’s neighbor used to fertilize crops was so strong that a county commissioner called out to look at the property ran to a nearby ditch to vomit.

What started as annoyance for the Washington state tree farmer became alarming when Guenther’s wife developed chronic bronchitis. It’s like clockwork, he says: Every time the sludge is spread, his wife’s health goes downhill.

“I have now a permanent raspy throat” from years of off-and-on illness, said his wife, Judy. The bronchitis’s full effect takes a few days to hit, but when she’s down, she can’t get out of bed.

Now, Guenther wants the treated sewage sludge, or “biosolids,” banned from agricultural land. They’re a nuisance, and using them risks contaminating water, crops, and livestock with “forever chemicals,” he said in a recent interview.

Guenther’s concerns, shared by other farmers and landowners, spurred Washington lawmakers to pass legislation, which is awaiting action from Gov. Bob Ferguson (D). It would require regulators to establish testing requirements for the chemicals, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), in biosolids by 2028.

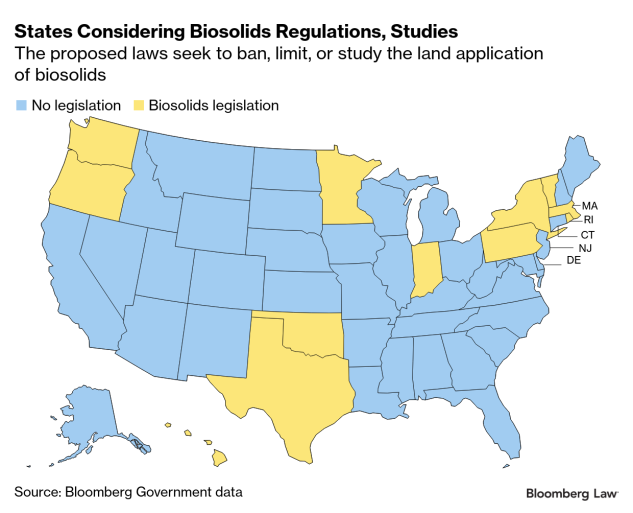

Similar worries prompted lawmakers in at least 11 other states to collectively introduce this year nearly two dozen bills tackling PFAS in sewage sludge. The measures include bans, testing, disposal guidelines, liability exemptions for water utilities and farmers, and aid for contaminated farms.

Yet, wastewater treatment plant officials warn about unintended consequences. Utilities or states could be left without viable options to manage the millions of tons of waste from homes, businesses, and stormwater drains.

Plants treat that muck to remove or reduce everything from condoms and keys to grit, metals, and disease-causing pathogens, transforming it into nutrient- and carbon-rich material that nourishes plants. Utilities manage biosolids by selling or offering them as fertilizer to farms, golf courses, and other properties. Incinerating or disposing them in landfills are used less frequently.

None of those methods destroy PFAS.

Nor are immediate solutions coming from the federal government, although Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin, announced plans on April 28 to address and control PFAS, including finishing an analysis of risks PFAS in biosolids may pose.

The public fears are driven by wreckage some PFAS have caused, the decades-long persistence of certain “forever chemicals,” and their association with a host of diseases.

There are thousands of PFAS and the risks of many aren’t clear, nor does detection alone mean all are dangerous since labs can measure them at vanishingly low levels. They’re also in thousands of products, and proven destruction technologies are scarce and expensive.

Pending State Legislation

Amidst this uncertainty, New York, Oklahoma, Indiana, and Vermont are among the states where lawmakers have introduced bills to either pause, limit, or ban spreading biosolids on land.

A Texas state representative offered legislation to ban sales and distribution of biosolids containing more than a certain amount of PFAS.

Other states, including Oregon and Pennsylvania, are weighing legislation to require biosolids testing or studies.

Wisconsin’s billwould exempt parties that spread biosolids from state requirements to clean up hazardous substances and report spills to regulators.

Existing State Policies

This year’s legislative proposals come on top of actions 10 states already took, according to an Environmental Council of the States report.

Utilities most frequently point to Maine’s and Michigan’s laws as more problematic and more practical, respectively.

Maine in 2022 became the first state to completely ban biosolids’ land application, triggering challenges the state’s still wrestling with, said Scott Firmin, director of wastewater services for Maine’s Portland Water District.

In 2018, Michigan started identifying industries releasing PFAS into wastewater and restricting effluents with excessive amounts of the chemicals.

Michigan later developed three management strategies for biosolids based on their concentrations of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctyl sulfonate (PFOS)—two long-lived PFAS often found in wastes and linked with illnesses including cancer.

The 2024 update to those strategies allows land application when concentrations of both chemicals are below 20 micrograms per kilogram and both the state and property owner receiving the biosolids are notified.

“Michigan took a smart, successful approach,” said Chris Peot, resource recovery director for the District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority, or DC Water.

Industrial effluent and other source control laws that place financial responsibility on industry and corporate entities—rather than on state or local government funding, utilities, or end users—are attractive and likely effective state strategies, said Catherina Narigon, an associate with Bergeson & Campbell PC, who coauthored a recent blog post on state effluent controls.

“The public generally wants to avoid PFAS entering into drinking water, crops, etc., in the first place,” and industrial effluent controls can help, she said.

But states must be careful, lest they shield an upstream source from liability, said Jean Zhuang, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center.

A company’s permit may require monitoring, so the business submits data to the state, she said. If the state doesn’t do anything, the company can be shielded from future liability, because it complied with its permit, Zhuang said.

Plus, controlling upstream sources alone won’t eliminate PFAS from biosolids, said Peot.

Laws and regulations barring PFAS from products where feasible are another essential source control, he said. “If we don’t do that, the chemicals will always be in biosolids.”

Continued research on technologies to reduce PFAS use and destroy them is essential, said Firmin.

Conundrum

When it comes to PFAS, “we don’t have the technology to treat wastewater in any practical or cost-effective manner,” said Kristina Surfus, managing director of government affairs at the National Association of Clean Water Agencies. “We’re just moving it around the environment, and that’s not solving the problem.”

Wastewater utilities are “stuck in between a rock and a hard place,” said Ana Schwab, a Best Best & Krieger LLP partner whose clients include treatment plants.

Utilities can’t comply with regulations without having cleanup standards and technologies, which they lack, she said.

The EPA had published neither final technology-based effluent limits for PFAS nor requirements to manage them in biosolids, according to the Congressional Research Service’s Jan. 15 update to lawmakers.

In his announcement, however, Zeldin said EPA will develop effluent limitations guidelines for PFAS manufacturers and metal finishers; evaluate other needed guidance to reduce discharges of the chemicals; and issue annual updates on how to dispose of and destroy them—a quicker turnaround than the current update every three years.

Superfund Liability

While work on standards and destruction technologies continues, Schwab said, Congress must protect wastewater utilities from the potential liability they face due to an EPA rule issued last year. It designated PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), or Superfund law.

Federal lawmakers are working on legislation to protect groups such as water utilities and farmers from Superfund liability and the burden of PFAS cleanups.

But Guenther, the tree grower in Washington, said parties spreading biosolids with PFAS should be liable. The risk to human health outweighs their benefits as a cheap, effective fertilizer, he said.

If biosolids’ use continues spreading, Guenther said, “eventually you’re going to have PFAS in every bit of drinking water in the United States.”

To contact the reporters on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.