Columnist David Lat interviews authors of a new academic study on the performance of Trump-appointed judges by measures of opinions, influence, and independence.

What makes a judge a “superstar” of the federal bench? And how do appointees of former President Donald Trump fare in terms of achieving superstar status?

With Trump running for president anew and four out of nine US Supreme Court justices in their seventies next year, these questions take on added importance. Justices tend to come from the ranks of lower-court superstars—so if Trump returns to the White House and gets to fill a seat (or seats) on the high court, he’d likely elevate one of his prior picks.

More than 20 years ago, New York University law professor Stephen Choi and University of Virginia law professor Mitu Gulati developed a methodology for evaluating judges that focused on three metrics: productivity, influence, and independence. They dubbed the judges with the highest overall scores “superstars” (with Judges Richard Posner and Frank Easterbrook of the Seventh Circuit as the top two back in 2003).

For a new paper, Choi and Gulati applied their framework to the 77 federal appellate judges who were 55 or younger in 2020—43 Trump appointees and 34 non-Trump appointees, roughly a 55%-45% split. The professors chose this group based on the reasoning that these jurists have the right combination of youth and judicial experience to be considered for the US Supreme Court in the near future. They referred to this judicial cohort as “auditioners,” since some of them appear to be “auditioning” for a spot on the high court.

After reading their paper and finding it intriguing, I interviewed Choi and Gulati earlier this week. I began by asking them why they decided to undertake this project—and why now.

“There was so much hot air in the media about Trump judges being unqualified buffoons,” Gulati explained. “I’m no Trump fan, so I was inclined to believe a lot of it. But Steve and I thought we should look at some data.”

“There’s always a lot of subjective, anecdotal information out there, like ‘this judge is precise’ or ‘this judge is good,’” Choi added. “We wanted to use objective measures. If you want to say Trump judges are bad or biased or don’t get cited, let’s look at the numbers.”

One possible prediction was that Trump judges would underperform. Based on Trump’s public pronouncements about how “his” judges would act and his own conduct in other spheres, some observers expected him to select judges based on their ability to deliver conservative outcomes or their personal loyalty to him—a “deviation from traditional norms of picking ‘good’ judges,” as explained in the study abstract.

But instead, according to Choi and Gulati, “Trump judges outperform other judges, with the very top rankings of judges predominantly filled by Trump judges.” This was, as Gulati told me, “not what we expected.”

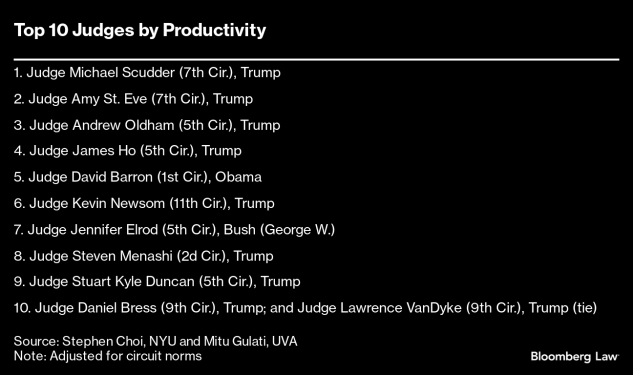

The professors prepared top-10 lists for various metrics. In terms of productivity (adjusted for circuit norms to reflect how much judges on a given circuit tend to publish), Trump appointees took nine out of the top 11 spots (11 because of a tie). Four of the top 11—Judges Andrew Oldham, James Ho, Kevin Newsom, and Stuart Kyle Duncan—have been mentioned by various publications as possible Supreme Court nominees in a second Trump presidency.

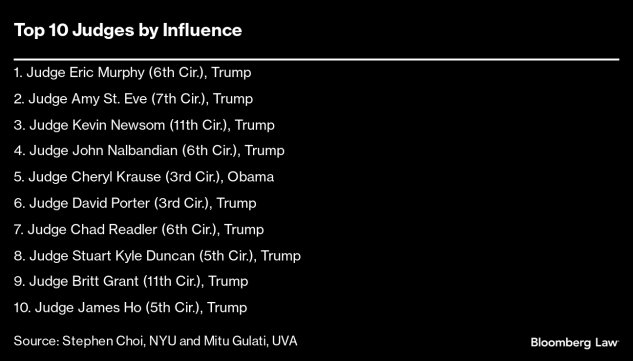

For influence, based on citations to a judge’s opinions by federal and state courts outside that judge’s home circuit, nine of the top 10 were Trump judges. Four of the 10—Judges Kevin Newsom, Stuart Kyle Duncan, Britt Grant, and James Ho—have been cited by news outlets as potential high-court picks in a new Trump administration.

Finally, the professors looked at judicial independence—which they also labeled “maverick” status, defined as “a judge who is willing to deviate from other judges, and particularly so those closest to them in terms of political ideology.”

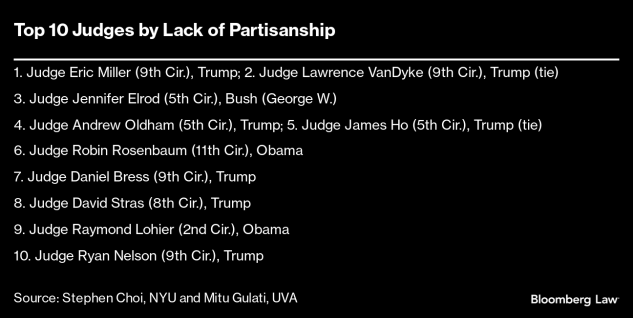

Their most interesting measure of independence was “partisanship” (or lack of), calculated based on how often a judge dissented against a majority opinion written by a colleague appointed by the same political party—e.g., how often a Republican appointee dissented from an opinion written by a fellow Republican appointee.

Of the least partisan judges, seven out of 10 were Trump appointees. Four of the 10—Judges Lawrence VanDyke, Andrew Oldham, James Ho, and David Stras—have been talked about in the media as Supreme Court contenders if Trump regains the White House.

To Choi, the dominance of Trump judges on the list of most independent jurists came as the biggest surprise: “I thought we would have found more bias—and it pointed out to me the value of having objective data.”

I was surprised as well. When I looked at the complete ranking of judges by partisanship in Choi and Gulati’s paper, the 10 judges who scored the lowest on partisanship—i.e., the judges who are supposedly the most partisan—seemed to me, based on my anecdotal sense of various judges, to be less partisan than Choi and Gulati’s top 10.

I asked the professors whether perhaps some of the Trump appointees might be scoring as “mavericks” because they are dissenting against fellow Republican appointees in a more conservative direction. They acknowledged this as a possibility and identified it as a subject for additional research.

Choi also suggested, however, that our anecdotal senses of judges might reflect cognitive biases, perhaps in favor of more recent cases or cases about hot-button issues that receive extensive news coverage. Their methodology gives equal weight to all cases, whether they concern abortion or ERISA. While Choi and Gulati have received some criticism for this, attempting to weight cases based on a subjective assessment of “importance” runs the risk of introducing the professors’ own biases into the mix.

It might be possible to evaluate the significance of cases based on a more objective measure—for example, the number of amicus briefs filed, which other professors have used to compare the salience of Supreme Court cases. This could be a fruitful follow-up inquiry.

And speaking of avenues for additional research, there are many other ways federal appellate judges could be ranked. One metric that sprang to my mind, given my (perhaps excessive) focus on credentials, would be a “prestige” ranking. It could include how often circuit judges are affirmed or reversed by the Supreme Court, how often they are cited with approval by the high court, and how often they send their own clerks into highly prestigious Supreme Court clerkships—i.e., so-called feeder judge status.

For now, Choi and Gulati should be commended for a valuable contribution to our understanding of federal judges and the federal judiciary. While specific rulings and opinions by individual Trump appointees are open to question and criticism, attempts to paint them with a broad brush as lazy, uninfluential, or partisan will need to engage with this research in a serious and sustained way.

David Lat, a lawyer turned writer, publishes Original Jurisdiction. He founded Above the Law and Underneath Their Robes, and is author of the novel “Supreme Ambitions.”

Read More Exclusive Jurisdiction

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.