In her column, Emory Law’s Tonja Jacobi writes about the US Supreme Court and legal ethics. Here, she shows the Chief Justice has more actively guided oral argument, even while his role in court decisions diminishes.

The power of Chief Justice John Roberts is being questioned, as court commentators talk about the “Thomas Court”—because of the ideological influence of Justice Clarence Thomas—or the “Kavanaugh Court” because Justice Brett Kavanaugh is now a powerful median.

As the new court term approaches, it’s important to understand that although Roberts may no longer be the court’s ideological center, he still has institutional power as chief justice of the US. And over the years he’s honed that power.

Five years ago, I co-authored a much-discussed study showing that female Supreme Court justices are interrupted disproportionately more than male justices. Male justices and male advocates were both especially prone to disproportionately interrupt the female justices.

Combating gender bias at the Supreme Court is important for its own sake—to ensure that every justice gets a chance to speak and ask questions of the justices. But at a time when the Supreme Court is struggling with historically negative public opinion, appearing to be fair is more important than ever.

The Supreme Court seems to agree. According to Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in its 2021-2022 term, the court changed the rules of oral argument to try to combat this gender disparity. In a recent study I co-authored with Matthew Sag of Emory Law School, we show something else has changed at the court, though less abruptly: Chief Justice Roberts has been increasingly stepping in to allow female justices’ voices to be heard as much as male justices.

The power of the chief justice is largely one of tradition. The only mention of the chief in the Constitution is in relation to impeachment of the president. But over time, chief justices have leveraged power—to assign opinions to the other justices, to preside over the justices’ voting and discussion at conferences, and to run oral argument.

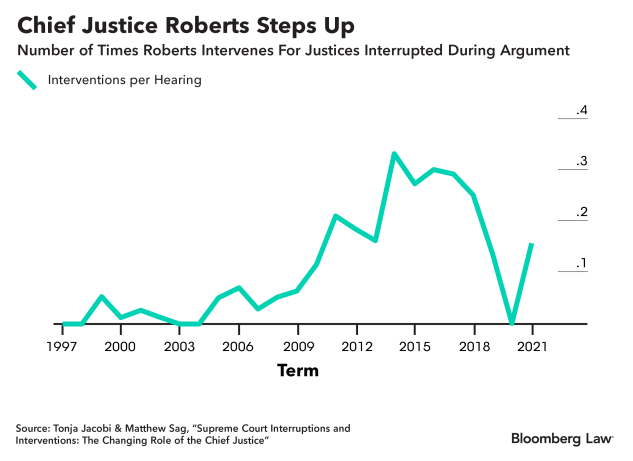

In our initial study on gendered interruptions, my co-author Dylan Schweers and I called for the chief to run oral argument better, by stepping in to give the floor back to a justice who is interrupted. The figure below from the newest study shows this is just what Chief Justice Roberts has been doing.

In the late Rehnquist and the early Roberts eras, the chief justice intervened 2.2 times per term; however, from the term beginning October 2010 to the 2021-2022 term, Roberts intervened an average of 13.25 times per term.

Even though interventions are still rare in any given oral argument, they are much less rare than they once were. The difference between before and after October 2010 is dramatic and statistically significant.

We looked at various ways the chief can intervene to help those who are being silenced regain the floor. Sometimes the chief will simply say the name of the justice who was interrupted. In many cases, Roberts says to a justice, “Go ahead.” And sometimes he will be more explicit, saying to the advocate—and implicitly to any other justice trying to interrupt—“Justice Sotomayor had a question,” as he did in Dollar General Corporation v. Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

For instance, in County of Maui, Hawaii v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund, Roberts interrupted advocate Malcolm Stewart to say, “Mr. Stewart, Justice Breyer has been trying gamely—to question you.” Stewart interrupted Robert’s mid-phrase to apologize.

Sometimes Roberts will keep an implicit queue. For instance, in Guerrero-Lasprilla v. Barr, Justice Elena Kagan had attempted to ask a question, then stopped to let the advocate finish his point. Justice Sonia Sotomayor had jumped in with questions. Roberts had allowed Sotomayor to ask multiple questions, some quite lengthy, but then eventually stopped her saying, “Mr. Liu, I think Justice Kagan had a question on the table.”

We counted the many ways this happened over the years, looking at every oral argument since 1997. Before the mid-1990s, oral argument was very different: The justices interacted less and interrupted each other less.

We have shown in another study that after the mid-1990s, justices were taking up almost 25% or more of the airtime than previously, but not asking any more questions, instead engaging in “judicial advocacy.”

But even in this new dynamic era, we found that Chief Justice William Rehnquist hardly ever intervened in this way at oral argument. And when Roberts became chief justice in 2005, he hardly ever intervened either. But, gradually, he began stepping in to correct interruptions.

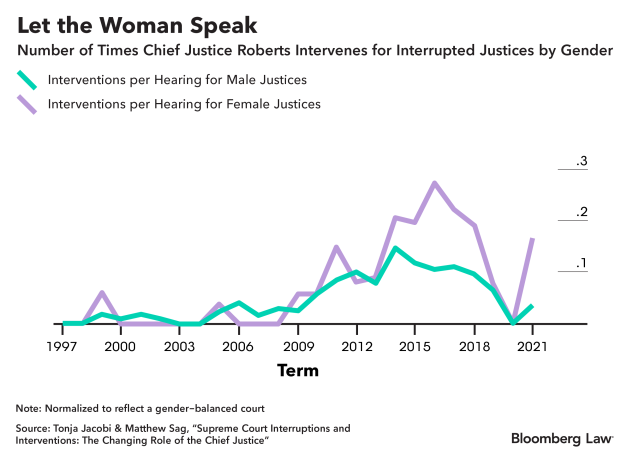

Ironically, at first, he intervened more on behalf of men than women, even while Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the only woman on the court, was being disproportionately interrupted. But over time, Roberts changed, seemingly recognizing the gender imbalance occurring before him.

Starting in the 2011–2012 term, Roberts began intervening more than twice as often, and eventually more than three times as often. And as the figure below shows, he started intervening more often when female Supreme Court justices were interrupted.

In the most recent term, Roberts intervened on behalf of female justices three times as often as for the male justices. This is appropriate since we also show the female justices are still interrupted significantly more by other justices, despite the rule change.

The attention given to the gender imbalance in interruptions and Supreme Court justices may not have reformed the behavior of the other justices, but it has changed John Roberts. And at least in that way, he has shown that he is still the leader of the court.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Author Information

Tonja Jacobi is professor of law and Sam Nunn Chair in Ethics and Professionalism at Emory University School of Law, where she specializes in Supreme Court judicial behavior and public law.

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.