Section I: Defining Shadow Banking

The term “shadow banking” has evolved considerably since economist Paul McCulley first used the phrase in 2007. At the time, McCulley was specifically referring to non-bank financial institutions in the US that had engaged in financial intermediation, such as maturity transformations, through which funding for long-term loans was being provided by short-term customer investments.

The risks posed by the banking industry’s financial activities were well-known during and after the 2008 global financial crisis. In the wake of the crisis, regulators around the world tightened oversight of the traditional banking sector. This bolstered the safety of one part of the financial sector. But lending—and risks—have since migrated to the non-bank credit industry, which has ballooned since the financial crisis, now managing over $75 trillion in assets, according to a recent report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

From global financial regulators’ perspectives, very little was understood after the 2008 crisis of how non-bank entities operated, whether they could contribute to systemic financial risks, and what could be done to regulate them. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) and other international agencies have been developing a strategy for strengthening regulation of the shadow banking system.

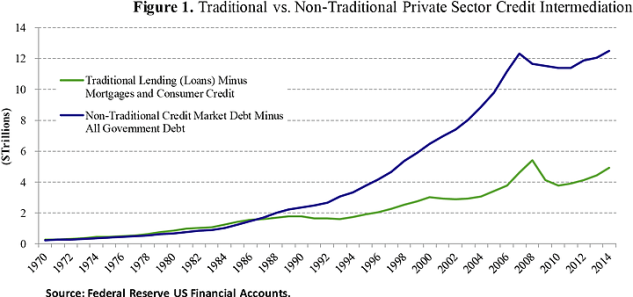

As depicted in Figure 1 below, until the late 1980s, non-consumer and non-government credit intermediation

While shadow banks do face their own set of regulatory standards and are likely to follow prudent internal risk management policies, as well as industry best practices, traditional banks face much stricter and more standardized regulations designed for minimizing risk and ensuring stability. Private equity funds and hedge funds are two types of financial institutions that generally face minimal regulatory oversight compared to the traditional banking sector. Figure 2 demonstrates the main differences in regulatory requirements faced by traditional banks and the asset management industry.

Shadow banks nonetheless have a variety of internal risk management measures that are designed to mitigate risks—specifically liquidity risk. Section II addresses funding benefits provided by wealth funds and risks facing asset managers, and how these so-called shadow banks manage such risks with relatively limited regulatory oversight.

Section II: Economic Benefits, Risks, and Risk Management

As highlighted above, the asset management sector has not been subject to the same regulatory constraints as commercial banks. Banks have relatively stringent capital standards set by the financial regulators, which are usually expressed as a capital adequacy ratio of equity that must be held as a percentage of risk-weighted assets.

Asset managers are also migrating into the credit intermediation market, (mostly through bond funds), as a result of the desire to generate greater returns, commonly known as the “reach for yield.” Since 2008, interest rates have declined to a historical low, with short-term interest rates approaching zero. This is partly due to the loose monetary policy initiated by many central banks around the world to support the economic recovery, including the “quantitative easing” programs conducted by the Federal Reserve system in the United States. Asset managers are increasingly looking for high-yield investment opportunities in order to produce higher returns for investment assets under management. Lending directly to companies is certainly one of these opportunities for fund managers, specifically for bond fund managers.

Benefits of Shadow Banking Supported by Funds

In principle, lending provided by asset managers is an important aspect of efficient capital markets, as the additional credit provision can be crucial to borrowers, especially when commercial banks are distressed. Smaller, less capitalized companies are poorly served by the official banking system. On the other hand, hedge funds, private equity funds, and other funds will often loan money to higher risk businesses, such as startup companies. The decision to lend is usually made after some due diligence, but with greater flexibility than what is provided by conventional lenders. An additional benefit of hedge fund loans is that access to funds is usually quick.

Risks Faced by Asset Managers

Fund-financed benefits of financing have their own costs, of course, as asset managers face risks arising from assets’ operational and regulatory structure. Shadow banks encounter many types of risks that may not typically affect conventional large banks. There are two main risk categories:

- Due diligence and credit risk: Do asset managers have the expertise to vet the companies they lend to? Do they know the background of packaged debt purchased by the fund?

- Liquidity risk: Banks have high capital reserves and access to an official liquidity backstop through central banks. Banks also have deposit insurance. The fund management community lacks these regulatory risk management tools. So what happens if there is a run on asset management funds, where investors withdraw money from the fund rapidly? Where can fund managers get temporary funding to cover liquidity needs?

Credit Risk

When extending a loan to a borrower, the process of accurately assessing the borrower’s credit risk requires the gathering and complete disclosure of financial information about the borrower. However, asymmetric information is constantly present, as borrowers almost never fully and voluntarily disclose all information. Incomplete and inaccurate information conveyed about the credit quality of a borrower may lead to inefficient pricing of the credit risk by lenders.

Banks have long-running and substantial experience in performing due diligence on borrowers. Shadow banks, on the other hand, may be relatively new to direct lending, and there are some concerns about their ability to perform detailed financial assessments of potential borrowers.

Liquidity Risk

Shares of open-end mutual funds and ETFs are usually redeemable or tradable daily, whereas invested assets can be much less liquid. Therefore, easy redemption options and liquidity mismatches between a fund’s assets and liabilities in theory can create run risks, when the suppliers of funds bail out en masse, leading to the threat of a fire sale of assets and further destabilization of the investment bases of funds. Adding to the risk of panic is the fact that investor funds held by asset managers are not insured by the federal government as bank deposits are under FDIC. Thus, investors faced with risk of losing uninsured funds may be less willing to stick with a struggling firm, elevating the potential for a large and rapid liquidity crunch. Large-scale asset sales made by funds to cover liabilities during a run may in turn exert significant downward pressures on asset prices, which could spread panic to other firms.

However, in practice, hedge funds, money market funds, mutual funds and ETFs very seldom experience industry-wide distress. Research by the IMF, however, shows that retail-focused mutual funds, which tend to be smaller in size, are more susceptible to runs on funds than funds tailored towards institutional investors, as retail investors tend to be more fickle with fund volatility. On the other hand, institutional investors are likely to be more sophisticated than retail investors, and they appear to be less influenced by recent past fund performance.

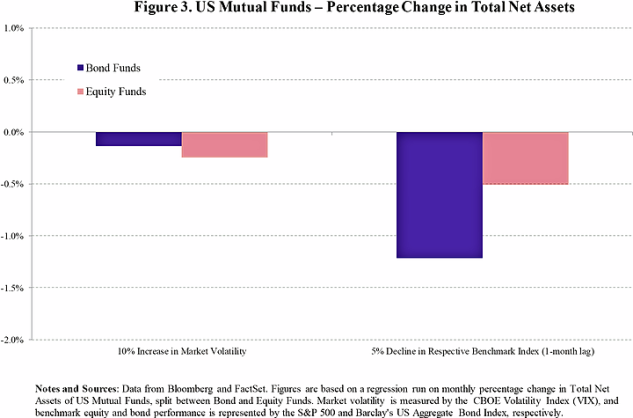

Since shadow banking is mostly facilitated through issuance of debt securities to investors, it is interesting to understand how bond funds differ from equity funds in response to market volatility and returns. NERA performed an analysis of the effects of market volatility and total returns on aggregate fund flows (see Figure 3). Our analysis shows the impact of market volatility and returns on bond funds and equity funds, respectively. If the contemporaneous market volatility, as measured by the CBOE VIX Index, rises by 10%, both aggregate bond funds and equity funds experienced a slight decline in total net asset value, with the percentage decline for equity funds nearly twice as large as the percentage decline for bond funds. As the regression model controls for market returns, we can interpret the asset value decline as a proxy for aggregate fund outflows

By contrast, aggregate bond assets experience a larger decline in value after a relevant benchmark index decline one month prior than aggregate equity assets do, though both assets experience a decline in value after the respective asset class experienced poor market performance. This indicates that investors may be pursuing momentum strategies that increase allocation to past winners and away from past losers, which in turn could exacerbate a liquidity crunch in a period of market stress. Our findings are similar to what the IMF concluded in their study.

Risk Management by Funds

When discussing risks posed by asset managers and other non-bank financial institutions, it is crucial understand how such non-bank firms implement a range of risk management strategies.

For example, hedge funds may charge high borrowing costs and impose prepayment penalties in order to offset potential credit risk posed by borrowers. While this may be subject to some pricing inefficiencies as a result of asymmetric information, as long as the hedge funds cover the hidden risks on average with cautious pricing, the likelihood of massive losses due to defaults by borrowers can be significantly reduced. Furthermore, in respect to liquidity risk, maintaining significant redemption fees for investors is one standard strategy used by asset managers to protect funds against a run. . Fees are effective to a varying extent in dampening redemption following short-term poor performance of the fund.

Additionally, non-bank financial institutions can tap into banks’ excess capital through borrowing as a type of liquidity risk management. Banks themselves have been shown to play an integral part in the shadow banking system as a whole. The latest Financial Risk Report released by the US Office of The Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) showed that US banks’ loans to non-depository financial companies have increased more than 230% in just three years.

Some credit and liquidity risks associated with intermediation activities have migrated into the shadow banking sector in recent years. As discussed above, tighter capital standards and liquidity requirements since the financial crisis will provide an increased incentive for credit intermediation activities to migrate from the banking system to the shadow banking system. However, this trend is counteracted by bank holding companies’ nimble adaptation to the new regulatory regime—vertical and horizontal integration between banks and non-bank financial institutions has accelerated since the financial crisis.

Systematic Risk and Shadow Bankers

Systemic risk, also known as aggregate risk or undiversifiable risk, can be defined as vulnerability to events which affect aggregate outcomes such as broad market returns. In the past, most of the focus for systemic risk was on the failures of large banking institutions. But there have also been recent, notable examples of collapses by wealth management funds that posed serious concern for the stability of the broader financial system.

The collapse of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) in 1998 is an example of how a large, highly leveraged non-bank financial company could potentially disrupt the stability of the wider financial system. LTCM experienced massive losses due to the Russian sovereign debt crisis in August 1998. Fearing the market fallout if LTCM was forced to rapidly liquidate its remaining positions, the Federal Reserve stepped in to organize a large bailout.

The 2006 failure of Amaranth Advisors, another large hedge fund, serves as a convenient counterpoint to the chaotic collapse of LCTM. In 2006, Amaranth reported to its investors that it had lost $5 billion in one week. The firm was then forced to liquidate its assets and close the fund, leading to concerns that the market would be destabilized.

Further concerns of systemic risk are highlighted by the recent episodes of “flash” crashes, such as the May 2010 stock market crash and the October 2014 crash in US Treasuries, where the combination of lower liquidity and flight-prone investors may have exacerbated the liquidity crunches, magnified price moves of underlying assets under management, and further destabilized asset bases.

The LTCM and Amaranth collapses show that neither size nor the mere status as a credit intermediary guarantees that a non-bank financial institution is systemically vital to the overall financial system. Both LTCM and Amaranth were large hedge funds that failed rapidly and without warning; however, in both cases the private sector showed the capacity for correcting for fund failure through emergency recapitalization.

In addition, research by the IMF confirmed that the size of a fund does not necessarily determine the systemic risk of that fund. Rather, a fund’s investment focus is more important. Furthermore, institutional investors appear to be less influenced by recent past performance and market volatility, as institutional investors are likely to be more sophisticated than retail investors. Hedge funds and private equity funds, therefore, may be less likely to experience run risks during a stress time, as they are primarily funded by institutional investors.

Section III: Regulatory and Litigation Risks

Uncertainty surrounding the shadow banking industry could have a large and sustained impact on both regulation and litigation trends in the near future. Regulators will continue to introduce stronger and possibly controversial measures of government oversight for non-bank financial institutions. At the same time, the migration of risk away from banks and into certain areas of the shadow banking sector will also pose difficult litigation challenges to non-bank credit intermediaries and government enforcers, which often operate in a regulatory gray area.

Regulatory Risks

US and international regulators have continued to push for increasing regulatory oversight of non-bank financial institutions. Specifically, regulatory agencies are considering an expanded use of the Systemically Important Financial Institution (SIFI) label to the asset management industry. Widespread use of SIFI would allow regulators to impose stricter and costlier regulations on mutual funds, hedge funds, private equity managers, and other asset management firms deemed systemically important. In the US, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) has been focusing on the systemic risks posed by the asset management industry.

y

Important Financial Institutions. Sharpe Funds Law.

The SEC’s new regulations for money market mutual funds (MMMFs) are a prime example of how the perception of systemic risk in the non-banking financial industry is leading to increased regulatory activity. Widely considered to be one of the safest investment vehicles available to investors, MMMFs typically maintain a net asset value (NAV) per share of $1, a sign of stability for their customers. The 2008 financial crisis, however, led to a series of liquidity crises for multiple MMMFs, including a large fund named Reserve Primary Fund, which was forced to lower its NAV per share to below $1, effectively “breaking the buck.” The panic that ensued forced the US Treasury to issue an emergency guarantee to investors that the value of certain money market fund shares would remain at $1 a share. As a direct consequence, the SEC imposed a long list of new compliance standards for MMMFs, including mandated stress testing and disclosure and liquidity requirements. While these regulatory requirements may enhance the level of government oversight and investor confidence in MMMFs, implementing and evaluating the effectiveness of new compliance measures will also impose significant costs on MMMFs, many of which may not present significant risk to the broader financial system.

In spite of the recent attention on regulatory oversight, a series of complex questions about the current state and future of the credit intermediation landscape remains. Are banks better equipped to provide stable and responsible credit intermediation than non-bank financial institutions? Is the capital base of a mutual fund, hedge fund, or other intermediary less stable than loans backed by traditional bank deposits, do they therefore require increased regulatory oversight? Finally, are fund managers more likely than banks to follow risky, short-term lending strategies?

Litigation Risks

In conclusion, non-bank financial institutions operate within a complex and rapidly evolving regulatory environment. Regardless of whether asset managers and other credit intermediaries legitimately pose systemic risk to the financial system, the fact remains that such institutions will face serious litigation risks as the debate over increased oversight of non-bank lending continues. Significant litigation risks include:

- 1. Redemption Disputes:Non-bank financial institutions are at significant risk for litigation dealing with fund redemption, specifically in disputes involving early redemption, redemption fees, and a wide range of other contractual obligations imposed upon both investors and asset managers.

- 2. Suitability, Investment Objective, and Disclosure Disputes:In an industry built on strategic diversity and innovation, asset management corporations are subject to considerable litigation risk involving fund valuation; investment objectives; disclosure and transparency practices; fiduciary obligations; and other matters that often fall into regulatory gray areas.

- 3. Securities Lending and Collateral Disputes:Non-bank credit intermediaries use a range of tools and strategies to collateralize lending, responsibly meet margin requirements, and maximize the returns of their portfolios. Disputes involving collateral eligibility and valuation, delays or failure to meet margin requirements, securities lending, repurchase agreements, and other complex transactions will remain an area of high risk for asset managers.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.