Introduction.

In private company mergers and acquisitions (“M&A”) transactions, the indemnification provisions of a definitive purchase agreement (whether asset purchase agreement, stock purchase agreement or merger agreement) stand out in importance for both buyers and sellers.

In addition to the general indemnities, parties to M&A agreements often also negotiate separate “stand-alone” indemnities - - indemnities which cover specific topics separate and apart from the general indemnities, and usually without reference to an underlying breach of representations, warranties or covenants.

This article examines the prevalence of stand-alone indemnities in private company M&A transactions and trends in that usage as reported in studies of the American Bar Association (“ABA”).

Stand-Alone Indemnities.

A typical indemnity section of an M&A purchase agreement could read as follows:

Indemnification by the Seller. The Seller agrees to and will defend and indemnify the Buyer Parties and save and hold each of them harmless against, and pay on behalf of or reimburse such Buyer Parties for, any Losses which any such Buyer Party may suffer, sustain or become subject to, as a result of, in connection with, relating or incidental to or arising from:

(i) any breach by the Seller of any representation or warranty made by the Seller in this Agreement or any Additional Closing Document;

(ii) any breach of any covenant or agreement by the Sellerunder this Agreement or any Additional Closing Document;

(iii) any of the matters set forth on Schedule [___];

(iv) any Taxes due or payable by the Company or its Affiliates with respect to any Pre-Closing Tax Periods; or

(v) any Company Indebtedness or Company Expenses to the extent not repaid or paid, respectively, pursuant to Section [___] and not included in the purchase price adjustment pursuant to Section [___].

Within the above provisions, clauses (i) and (ii) - - which are tied to breaches of representations, warranties and covenants - - would be considered general indemnities and clauses (iii), (iv) and (v) would be stand-alone indemnities.

In addition to the common connection between general indemnities and a breach of some type, there are often other differences in treatment with stand-alone indemnities. General indemnities are usually subject to both “baskets” (whereby the indemnitor is not liable for breaches until a specific level of indemnitee losses are reached) and caps (limiting the indemnitor’s overall liability for breaches), and the underlying representations and warranties to which the general indemnities apply often expire after a prescribed time period, usually prior to the otherwise applicable statute of limitations. Of course, there are often exceptions to this general construct - - for example, representations and warranties which are determined to be “fundamental” by the parties (such as those regarding title, authority, taxes, ERISA and the like) may be subject to the general indemnities but have no basket or cap (or a different basket or cap) and different expiration period.

By contrast, stand-alone indemnities often are not subject to baskets, caps or specific time periods (though the parties are free to negotiate specific baskets, caps and expiration dates for these indemnities, and sometimes do).

There can often be overlap (and some redundancy) between topics and matters covered by general indemnities and stand-alone indemnities. As one common example, and as reflected in the language above: a common stand-alone indemnity relates to pre-closing taxes, but the typical M&A purchase agreement also includes a tax representation (which is often not subject to a basket or cap).

Generally speaking, stand-alone indemnities tend to cover two separate types of matters:

- matters for which the buyer does not wish to assume any post-Closing responsibility, whether or not those matters constitute a breach otherwise covered in the M&A purchase agreement, and whether or not those matters arose as a particular concern during the buyer’s diligence; and

- matters arising during the buyer’s diligence that pose unusual or unexpected risk.

With respect to the first category, these matters may include tax, ERISA and environmental liabilities (or other “excluded” liabilities), and target indebtedness and transaction expenses (such as investment banking, accounting and legal fees). Using taxes as an example, a buyer may - - not unreasonably - - take the position that it should never be responsible for paying the seller’s taxes, whether or not a breach of the tax representation has occurred, and that the seller’s liability to pay its taxes - - vis a vis the buyer - - should not be subject to a basket, cap or time period shorter than that otherwise applicable.

With respect to the second category, during the M&A due diligence process, the buyer may discover certain matters that may need to be singled out and treated as a special issue covered by a stand-alone indemnity. A stand-alone indemnity reallocates the risk of losses that may have an adverse impact on the target’s business post-closing. For example, the buyer might learn during its due diligence that the target’s best-selling consumer product may contain traces of lead potentially harmful to children, something both material and presumably unexpected. The buyer will be concerned about the potential financial loss resulting from product liability lawsuits and possible damage to the product’s brand name and reputation- - potential exposure that the buyer may not have taken into account in assessing and pricing the transaction. As such, the buyer may require that seller provide a stand-alone indemnity to cover all associated losses.

Buyer’s and Seller’s Perspectives.

While most M&A agreements include representations, warranties and covenants from both the seller to the buyer, and the buyer to the seller, as a practical matter the scope of representations, warranties and covenants, and related indemnities, from the seller are usually much broader in scope and substance than those from the buyer. This is not surprising since the seller’s representations and warranties, for example, will cover a wide range of financial and operating matters relating to the target. By contrast, the buyer’s representations and warranties tend to focus on its ability to consummate the transaction and perform its obligations.

Accordingly, the seller is usually more inclined to limit the scope of indemnities overall, whether those are of the general or stand-alone varieties. The buyer, on the other hand, has a corresponding desire to expand that scope to the extent possible.

Trends in Stand-Alone Indemnity Provisions.

In 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011 and 2013 the ABA released its Private Target Mergers and Acquisitions Deal Points Studies (the “ABA studies). These studies look at certain publicly available M&A agreements for transactions that occurred in the year prior to each study. In each year, the studies reviewed 128, 143, 106, 100 and 136 private company transactions, respectively. These transactions have ranged in size from $17 million to $4.7 billion, across a broad range of industry sectors.

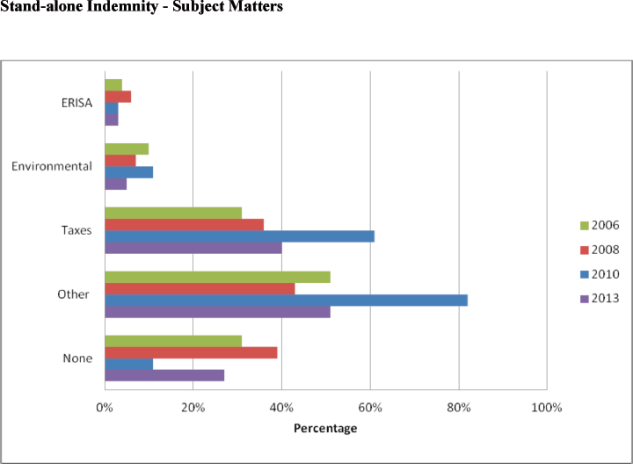

According to the 2013 study, 3% of the agreements included stand-alone indemnities on ERISA issues, 5% on environmental issues, 40% on taxes and 51% on “other” issues - - identified in the 2013 study as frequently including “inaccuracies on payment spreadsheets; excluded or retained liabilities; and dissenters’ rights/dissenting share payment claims.”

The 2011 study showed corresponding percentage levels 3%, 11%, 61% and 82%, respectively, with 11% of the agreements having no stand-alone indemnities. The 2009 study showed percentage levels amongst the various subject matters at 6%, 7%, 36% and 43%, respectively, with 39% of the agreements having no stand-alone indemnities. The 2007 study reflected percentage levels amongst these subject matters at 4%, 10%, 31% and 51%, with 31% of the agreements having no stand-alone indemnities.

The chart below illustrates the frequency that various subject maters of stand-alone indemnities appeared in private company M&A agreements (by percentage, according to the four most recent ABA studies).

Stand-Alone Indemnity - Subject Matters.

Assuming that the ABA studies reasonably reflect general practice in M&A transactions, it appears that the usage of stand-alone indemnities overall reached a peak in 2012 (as reported in the 2013 ABA study). Stand-alone indemnities for ERISA and environmental issues seem to be consistent, and relatively rare, while stand-alone indemnities for tax and “other” issues are more commonplace.

Conclusion.

Stand-alone indemnities are not typically subject to the same limitations, as to amounts and time periods, as general indemnities, nor do they depend upon an underlying breach by the indemnifying party. As such they may more readily shift risk back to the indemnitor than general indemnities, even if covering the same sets of risks. Accordingly, these provisions should be carefully considered in the overall context of the transaction and the agreed-upon risk allocation as between buyer and seller.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.