In mergers and acquisitions (“M&A”) transactions, the definitive purchase agreement (whether asset purchase agreement, stock purchase agreement, or merger agreement) typically contains provisions for post-closing purchase price adjustments.

In 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2013 the American Bar Association (ABA) released its Private Target Mergers and Acquisitions Deal Points Studies (the “ABA studies”). The ABA studies looked at the M&A agreements of publicly available transactions that occurred in the year prior to each study. In each year, the studies reviewed 128, 143, 106, 100 and 136 private company transactions, respectively. These transactions ranged in size from $17 million to $4.7 billion, across a broad range of industry sectors.

This article examines trends in the usage of purchase price adjustments in private company M&A transactions, as reflected in the ABA studies.

Purchase Price Adjustment Provisions

General Overview

As noted above, purchase price adjustment provisions are designed to reflect changes in the target’s financial condition which occur prior to the closing of the transaction. By way of example, if on January 1, a transaction is valued, or priced, at $10,000,000 when the target has inventory worth $100,000, and if, when the transaction closes (all other financial metrics being equal), the seller delivers the target with $500,000 of inventory, the seller will expect to be paid (often dollar-for-dollar) for the additional $400,000 of added, measurable value. Similarly, if at closing the target’s inventory is valued at $50,000, the buyer will look for a reduction of purchase price in that amount.

Since purchase price adjustment provisions are intended to put the parties on an equal footing, as of the closing date, to reflect pre-closing changes in financial condition, these provisions are not normally viewed as benefitting or favoring a buyer or seller. Instead, they are considered neutral as between the parties to an M&A transaction.

Once the parties to the transaction have agreed upon a purchase price for the transaction (even if that agreement is subject to satisfactory completion by the buyer of its due diligence or other conditions), the lawyers are often asked to memorialize three aspects of that purchase price agreement: (1) the particular financial metric to be used for purchase price adjustment purposes; (2) the benchmark amount of that metric against which the corresponding closing amount is to be measured; and (3) the specific procedures pursuant to which the adjustment is to be determined whether before and/or after closing.

Common Financial Metrics Used in Purchase Price Adjustments

Purchase price adjustment provisions can be based on any number of financial metrics, though most frequently these provisions are tied to changes in working capital. Working capital is normally determined under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) as the excess of the target’s current assets (cash, inventory and accounts receivable) over the target’s current liabilities (ordinary course payables and other short-term obligations payable within one year). Since working capital is the most common metric used in M&A purchase price adjustments, for simplicity, this article looks at adjustment provisions which are based on changes in working capital.

A sample purchase price adjustment provision is as follows:

The Purchase Price shall be adjusted dollar-for-dollar: (a) upward by the amount (if any) by which Working Capital as of the opening of business on the Closing Date shown on the Closing Statement (the “Closing Working Capital”) is greater than Target Working Capital; or (b) downward by the amount (if any) by which Closing Working Capital is less than Target Working Capital.

Establishing the Benchmark Amount

In the purchase price example provision above, the benchmark amount of working capital is referred to as the Target Working Capital. This will typically be a set amount agreed to by the parties. Sometimes the parties will look to determine the benchmark working capital amount as of the time the transaction was “priced.” This may be easier said than done. For example, it is not often clear when the transaction was priced by the buyer or exactly when the price had been agreed between buyer and seller. Was it the time that a letter of intent was signed? Or was it a different time, such as when the buyer completed its initial financial due diligence?

In addition, in many business sectors the working capital of the target may fluctuate seasonally or otherwise, so the selection of a certain date by which to calculate the benchmark working capital may be far from perfect. Therefore, in order to address these fluctuations the parties may seek to determine a “representative” level of working capital as the benchmark.

Purchase Price Adjustment Procedures

If the parties agree to utilize a purchase price adjustment, then that adjustment (again using working capital as the adjustment metric) would most commonly be structured along the lines of the following:

(1) Since it usually takes some time after the closing to determine with any meaningful degree of precision what the target’s working capital was as of closing, the adjustment is implemented following closing. However, if the parties believe at or prior to closing that the target’s working capital level is likely to be materially different (whether up or down) than the benchmark, they may agree to a purchase price adjustment as of closing based on best estimates of closing working capital, and then do a second post-closing adjustment off of that revised amount. For example, if the purchase price is $100 and the original target (benchmark) working capital level is $10, and the parties agree prior to closing that the closing working capital level is likely to be closer to $25, rather than do the entire adjustment post-closing, they may decide to: (i) adjust the purchase price payable at closing to $110 to reflect the likely additional $15 of working capital ($25-$10), and (ii) have a post-closing adjustment using $25 as the new benchmark for working capital.

(2) Following the closing, either the buyer or the seller would have a set period of time to submit a calculation of closing working capital to the other party, along with the submitting party’s calculation of the resulting adjustment to the purchase price.

(3) The party receiving the calculation would then have the opportunity to dispute the calculation; often if a dispute is not sent to the submitting party within a specified time period, the submitting party’s calculations are deemed to have been accepted.

(4) If there is a dispute, often the agreement will require the parties to seek to resolve their disagreements to the extent possible. Any disputes that cannot be resolved within the specified time period would typically be resolved by a third party in a non-judicial setting (often by a nationally recognized accounting firm or other professional expert with knowledge of the relevant industry). The third party arbitrator may be selected in advance by the parties, or the purchase agreement may instead set forth the procedures by which the arbitrator (or arbitrators, as there may be more than one) is selected.

Trends in Purchase Price Adjustment Provisions

According to the ABA studies:

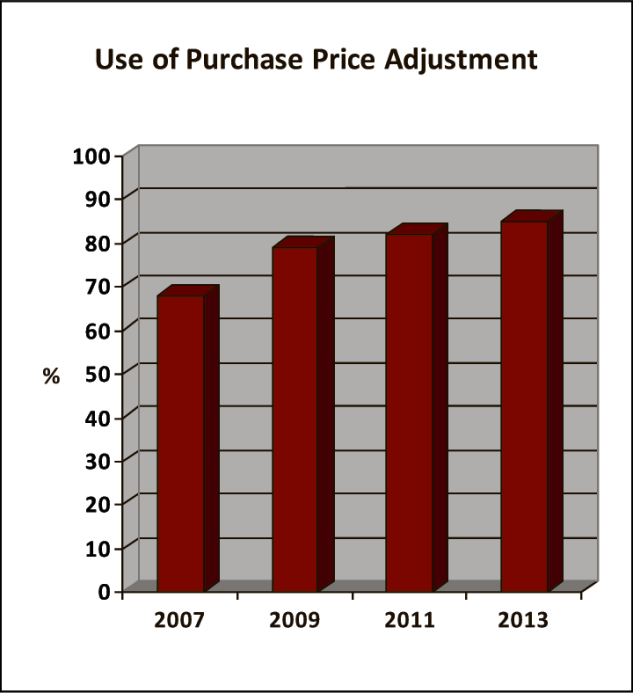

(a) Use of Purchase Price Adjustments. Purchase price adjustments continue to be commonplace: 85% now, up from 82% in the 2011 study, 79% in the 2009 study, and 68% in 2007.

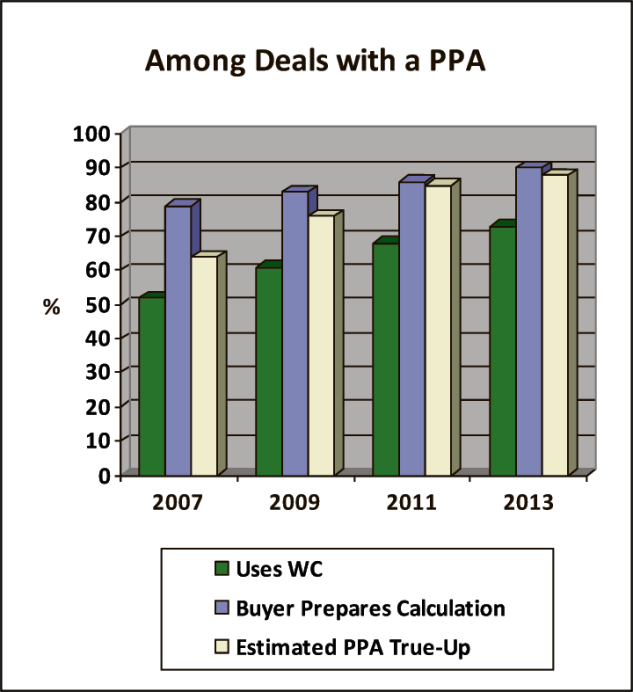

(b) Adjustment Metrics. Working capital is the most common purchase price adjustment metric—currently at 91%, up from 79% in 2011, 77% in 2009, and 69% in 2007.

(c) Preparation of Initial Adjustment Calculation. The buyer is increasingly the initial post-closing preparer of the purchase price adjustment calculation: 90% in 2013, 86% in 2011, 83% in 2009 and 79% in 2007.

(d) Pre-Closing True-Up. More deals have an estimated purchase price adjustment true-up at closing: 88% in 2013, 85% in 2011, 76% in 2009 and 64% in 2007.

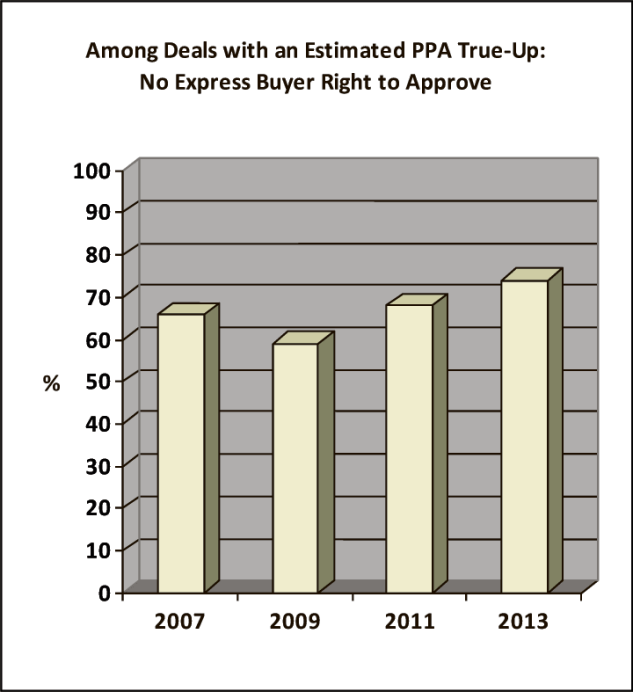

(e) Buyer Right to Approve Estimated Adjustment. Increasingly, there is no express buyer right to approve the closing estimated adjustment: In 2013, 74% of the deals had no express right, with 68%, 59% and 66% in the prior three studies.

The following shows the information above in chart format:

Conclusion

Many of the provisions of a purchase agreement, such as the representations and warranties, will reflect an allocation of risk between the seller and buyer as to a broad range of topics and matters, including not only financial matters but also areas such as compliance with laws, labor and employment, employee benefits, contracts, operations in the ordinary course of business, title, sufficiency of operating assets, and the like. The buyer and seller may have different views on their respective risk tolerance as to different matters (for example, the seller of a service company with no owned real estate and no manufacturing may have a relatively relaxed view about allocation of environmental risk), and, as such, some of these matters may be negotiated to a “pro-seller” result, and vice-versa. In addition, assuming appropriate disclosures by the seller and thorough diligence by the buyer, these provisions may in some circumstances be considered to address “what-if” or even “low risk” issues occurring after the closing.

On the other hand, purchase price adjustments are viewed as being linked (often dollar-for-dollar) to the purchase price, in amounts which should be readily calculable, and determinable shortly after closing. The adjustment provisions, while usually quite straightforward, are nonetheless important to ensure that the parties receive the economic results they bargained for.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.