For the past two decades, a rapid and ongoing evolution has been taking place in today’s communication media environments. Technology and social media have increased exponentially the American consumer’s options for both intentional and random information gathering and learning. And, as more and more people move away from traditional avenues of receiving news and other information and toward electronic media, courts and litigants must fashion contemporary notice programs to communicate with absent class members in ways that will both resonate with these changing preferences and continue to be consistent with due process and Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(c)(2)(B).

Over forty years ago, in the Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacqueline, 417 U.S. 156 case, the Supreme Court quoted its decision in the seminal notice case of Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co, 339 U.S 306, and declared that in in rule 23(b)(3) class actions, “notice must be ‘reasonably calculated under the circumstances, to apprise interested parties of the pendency of the action and afford them an opportunity to present their objections.’ ” The Court’s rationale calls for flexibility in formulating notice programs, which is consistent with the current proposed changes to rule 23’s notice provisions. Indeed, as the communication media environments continue to evolve, it is not hard to imagine a time when modern media channels may surpass First Class Mail as the most desirable means for providing individual notice to absent class members. See, e.g., Browning v. Yahoo! Inc., 2006 WL 3826714, N.D., C04-01463HRL, 12/27/06 (ordering email notice).

Supreme Court Precedents, Rule 23(c)(2)

Allow Flexibility in Choosing Notice Methods

Although Eisen and Mullane were decided before the Internet and electronic forms of communication existed, the Supreme Court in those cases wisely provided an approach to notice guided by intent and practicality. The Court specifically warned against notice procedures as “mere gesture[s],” instead directing that the means employed should reflect a desire to “actually” inform absent class members of the pending action. Eisen, 417 U.S. at 174 (quoting Mullane, 339 U.S at 315). It explained, the reasonableness and thus the constitutional legitimacy of any chosen method could be defended as long as the method was reasonably certain to inform those affected.

As currently written, in opt-out classes, rule 23 (c)(2)(B) requires giving class members the “best notice that is practicable under the circumstances, including individual notice to all members who can be identified through reasonable effort.” While it provides specific rules as to the information that must be included, it does not specify any particular preferred means of notice. Unfortunately, since Eisen, many courts have interpreted this rule to require notice by First Class Mail in every case. See Advisory Committee on Civil Rules, Report of the Advisory Committee on Civil Rules, Committee Note, 254, Tab 4, p.4 (May 12, 2016) http://www.uscourts.gov/rules-policies/archives/agenda-books/committee-rules-practice-and-procedure-june-2016/. Thus, when electronic notice has been approved as part of a notice program, it has generally not replaced, but has rather supplemented, other more traditional forms of notice. For example, in the NFL Players’ Concussion litigation, the court approved a class settlement notice program in which three professional notice firms were hired, individual notice was provided by First Class Mail, extensive media publication occurred in magazines and on television, a toll-free number was set up, and a website was maintained. In re NFL Players’ Concussion Injury Lit, 307 F.R.D. 351, 821 F.3d 410, E.D. Pa., aff’d.

Rapidly emerging, multiplatform on-demand media channels are driving the way consumers interact with and use new media to communicate. American consumers are using media as a seamless on-demand interconnection, using multiple devices and multiple media channels – sometimes all at once, gathering information when and where they want it.

And, it stands to reason that this on-demand expectation regarding media use, may be at least one of the factors driving the decline in volume of U.S. First Class Mail. According to the website internetlivestats.com, today 88% of adults in the United States have access to the internet, whether at home, at work, at school, at a library, or on a mobile device. In a recent report by the Pew Research Center, investigators found over the past fifteen years, online usage among adults between the ages of 18 to 29 increased from 70% to 96%, and the growth among senior citizens has been even greater, increasing from 14% to 58%. As new forms of communication increase in popularity, the reliance by the public on any given means of communication will necessarily continue to evolve as well. For example, the astonishing adoption of smartphone technology has and will continue to drive condensed forms of communications and electronic messaging on a small screen, whether through the use of a cellular device or a tablet.

Given consumers swift adoption of electronic means of communication, the Supreme Court’s directive that notice be “reasonably calculated, under all the circumstances, to apprise interested parties of the pendency of the action and afford them an opportunity to present their objections” should be understood to allow notice by means entirely other than First Class Mail where appropriate, making the proposed revisions to rule 23(c) particularly timely.

On May 12, 2016, the Advisory Committee on Civil Rules proposed changes to Rule 23(c)(2)’s notice provision, among other things. Fittingly, the changes emphasize the need for courts to exercise discretion in selecting appropriate means for giving notice to class members. The proposed rule would provide the following: “The service may be by United States mail, electronic means, or other appropriate means.” But the Committee notes make clear that electronic notice may not be appropriate in every case, and courts should consider certain factors when deciding how to provide the most effective notice in a given case. Such factors include the anticipated delivery rates, the likelihood that class members will pay attention to messages delivered by different means, the content of the notice, and the format of the notice. In addition, if electronic means are used, courts should consider class members’ ability to access to online resources, their receptivity to the manner of presentation, and the expected response from class members. Advisory Committee on Civil Rules, Report of the Advisory Committee on Civil Rules, Tab 4, p. 2 (May 12, 2016), available at http://www.usgov/rules-policies/archives/agenda-books/committee-rules-practice-and-procedure-june-2016/.

Building Blocks for Effective

Contemporary Notice Methods

As the committee notes suggest, not all class actions are the same. Thus, common sense should prevail when contemplating what means should be employed to reach potential class members in a way that is more than a “mere gesture” when providing notice and due process. Determining absent “class members’ receptivity to the manner of presentation” requires courts to take into account many variables. Some of these variables should focus on the company’s behavior—such as how it markets to its customers, how it collects data for ongoing communication, how and whether the company authenticates consumer contact data, and how and whether it keeps that data current. Other factors should focus on the absent class members’ characteristics—such as their ages, their familiarity with the company, and the ways in which they generally communicate with others. In some cases, determining which channel is best to reach a potential class may require the use of complex demographic and qualitative behavioral studies. In such cases, a well-respected media research data company, such as Nielsen, GfK Mediamark Research & Intelligence, LLC., or a similar company, can provide indispensable information as these kinds of companies specialize in collecting data, such as age, income, gender, and other important qualitative human behaviors that allow them to identify what media channels different groups prefer to use.

After all, understanding how a company communicates with its market is the lynchpin to determining what method of providing notice would be most effective. For a variety of reasons, including cost and customer preference, companies are shifting from direct mail communication to email or other electronic forms of communication to interact with their customers. According to the most recent Direct Marketing Association Response Rate Report, 44% of those companies are employing multiple channel communication for contacts, for example, communicating through some combination of email, direct mail, apps, and online communication.

In addition, knowing how a company acquires a contact list is critical because not all contact lists are equal. Indeed, consumers can spoil their customer data by providing inaccurate or partial contact information, such as providing false or secondary contact information when signing up for loyalty programs or free offerings in an attempt to minimize junk mail, either through U.S. mail or email. In addition, loyalty information may quickly become stale if not scrubbed at certain intervals. In contrast, well groomed, marketing/transactional contact data, or house-list data, which is collected and maintained by businesses for their own use, will be much more likely to apprise interested parties of an ongoing action than contact data gathered from loyalty or other free offer sign-up programs. Consumers are more likely to pay attention to communication from sources with which they are familiar. Conversely, a lack of immediate familiarity with the company may potentially lead recipients to discard attempted communications as junk. Thus, marketing and ongoing business-to-customer lists tend to be trusted and up-to-date. If a company has used that kind of list as part of its marketing or promotional efforts, and it conducts regular list hygiene updating contact information as it changes, then the company will already have an understanding of what the deliverability rate of communications with its customers has been.

On the other hand, if the list is stale, or the successful deliverability rate has been historically poor, there is little reason to believe a court order that requires information to be delivered using that list would result in a better deliverability rate. In fact, using old or stale lists that rely heavily on a United States Postal National Change of Address look up may result in at least one-third of the correspondence not being delivered because nearly 12% of consumers move each year, and more specifically, 25% of renters move each year. http://www.nationalchangeofaddress.com/FAQs.html.

Turning to the characteristics of absent class members, providing effective contemporary notice requires expertise in media relevance, which means knowing which media to use in different kinds of potential class actions—i.e. direct mail, email, or other electronic outreach—which in turn requires figuring out when, where, and how absent class members prefer to communicate. In addition to direct mail, people now send and receive messages on their laptops, desktops, tablets, smartphones, and smart watches; moreover, they communicate at home, at work, and on-the-go. Determining communication preferences is further complicated by the fact that consumers may use media concurrently, perhaps reading an email on a smartphone and responding to it on a computer, depending on the situation.

Direct Mail Notice Compared

With Other Direct Communication Methods

While some may disagree with the proposed rule changes and prefer the status quo, arguments that merely compare the utility of direct mail and email, or other forms of digital or electronic notice, in broad strokes fail to recognize the complexity inherent in determining the efficacy of various notice methods in different kinds of cases. Therefore, media analysis based on generalizations will not always provide a true picture of a communication method’s potential effectiveness (or cost efficiency). Through a generalized lens, it appears on average that direct mail outperforms other methods of communication across all demographic categories. But in each case, courts should consider whether direct mail is likely to outperform other available communication methods for providing notice to absent class members, given the particularities in each case. Indeed, the likelihood that direct mail actually outperforms or will continue to outperform other communication methods in every case is far from certain. Broad preferences for direct mail appear to be decreasing in favor of other communication methods. And regardless of the method chosen, factors such as the familiarity with the sender, the length of the notice, and the age of the recipient all play important roles in the efficacy of the attempted notice.

The Direct Marketing Association reports that from 2003 to 2014, the response rates to direct mail house lists had a slight decline from 4.36% in 2003 to 3.73% in 2014. Further analysis by age group reveals that recipients over the age of 35 were more likely to respond to this type of mail than younger recipients. About 10% of 18 to 34 year-olds will respond to direct mail. For those over the age of 35, between 12% to 14% indicate they would respond to direct mail.

Moving to First Class Mail, for the past 30 years about 10% of consumers consistently have indicated that they will respond to communications sent by First Class Mail. But upon closer analysis, it appears other factors play an important role in potential response rates to traditional mail, whether direct mail or First Class Mail. Familiarly with an organization increases the overall potential response to 18.4%. Consumers also tend to favor postcards over other forms of traditional mail, with over 50% reporting that they look at the postcards they receive. Hence, familiarity with an organization and the ability to quickly scan information can improve response rates to traditional mail.

A similar analysis of email reveals that using house lists of email addresses, combined with the recipients’ familiarity with the sending company, results in an average open rate, meaning a recipient opens an email, of approximately 23% to 24%. Nearly 8% of recipients click a link to receive information. And nearly 3% will take some action in response to the emailed message. Additional instruction is found in the analysis of action taken by age group and the device that they use to view an email. Over 46% to 58% of 18-54 year olds look at email “on the go.” http://www.fluentco.com/resource/the-inbox-report/. Between 63% to 72% of these individuals look at email on a smartphone. Similar to recipients’ response rates to postal mail, email open rates are positively affected by familiarity with the organization sending the email, the existence of an ongoing relationship with the sending company, the degree of personalization in the email, and the length of the subject line. Therefore, to improve the efficacy of the notice, the email messages must be thoughtfully personalized and optimized for quick scans on small screens. See Marcia Kaplan, Email Still Effective Marketing Tool? Practical Ecommerce (June 5, 2013). Again, common sense applies.

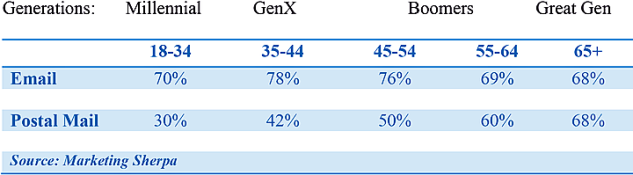

If a company transacts its normal business through electronic means (whether email or app), then necessarily, notice should follow that communication path. Recent studies by both the Principal Financial Group and Marketing Sherpa reveal strong inverse communication preferences by age group.

The chart above illustrates generational preferences for communication in comparison to preferences for communication through postal mail. Due Process within the class context must now consider media consumption and human behaviors in order to ensure notice is reasonably calculated to apprise absent class members of the action and afford them an opportunity to present their objections or opt out. The media ecosystem is far more complex than it was when Eisen was decided.

One does not need to ask “if” consumers use email, but “how” they use email. The American consumer’s inbox has undergone a great deal of change over the past ten to fifteen years. In 1990, email may have included a scanned plain text from a sender, no images. By 2000, email included graphical interfaces, links, images. In the future, we may see authentication near a sender’s subject line, which will move email from a passive delivery channel into the realm of interactive and on-demand communication, which sorts email by context and Big Data—not simply by the date received. This is already happening. The nascent steps are found with Google Now, Gmail’s Priority Inbox, Outlook’s Clutter feature, all of which employ a user’s behavioral, geographical, or contextual cues to prioritize and categorize email. Chad White (ed.), Email Marketing in 2020: 20 Experts Share Their Visions of the Future of the Channel, litmus, 4-5 https://litmus.com/lp/email-marketing-in-2020. A number of industry experts predict the email expansion will continue, largely because most all applications and channels of communication are now tied to email. Id. This includes social media and big data matching on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, as well as on the Internet of Things.

Credible leading Notice Experts are already matching big data to specifically target and serve advertising to individuals on social media based on their email addresses and other publically available data sources. See, e.g., Declaration Jeanne C. Finegan, Concerning Implementation and Adequacy of Class Member Notice Program. In Re: Blue Buffalo Company, LTD Marketing and Sales Practices Litigation, Case No. 14-md-02562, (E.D. Mo.) (2016). Using this kind of data, it is possible to specifically target absent class members who are purchasers of certain brands and serve display banner ads to them as part of an individual notice program. While some may argue that display banners are passive and that they cannot accommodate sufficient space to serve the kind of an entire summary notice to satisfy due process and the federal rules, specific programming can actually allow a recipient to scroll through a banner ad that would display all the information listed in Rule 23(c)(2)’s notice requirements.

Even without programming banner ads to allow additional information, these ads can play an important role in individual notice programs. In traditional individual notice programs, paper envelopes containing the requisite notice information are sent through the postal service to absent class members with the hope that they will open the envelopes, receive the requisite notices, and respond if they so desire. One may analogously view a banner ad as a type of envelope electronically sent to identifiable absent class members with the hope that they will click a link that takes them to a website where they can receive the requisite notices, along with the opportunity to respond if they choose to do so.

Pharmaceutical companies have employed this approach in advertisements to meet FDA requirements regarding information that must be provided in such communications. However, this type of ad comes at a higher cost. In this context, courts should be guided by the Supreme Court’s instruction that “reasonableness and [the] constitutional validity of any chosen method” should depend on whether the method is “reasonably certain to inform those affected,” and the fact that rule 23 does not specify where in the communication funnel a detailed notice must appear or what method must be used to be provide such notice to absent class members. Certainly, online advertising (if planned, validated and reported correctly by using reasonably relied upon advertising industry tools and methods) has been an enormously effective tool in numerous class action settlement outreach programs, as one of the authors has helped develop in a number of other cases. See, e.g., Declarations of Jeanne C. Finegan, In Re: Blue Buffalo Company, Ltd., Marketing and Sales Practices Litigation, Case No. 4:14-MD-2562 RWS (E.D. Mo. 2015), and In Re: TracFone Unlimited Service Plan Litigation,No. C-13-3440 EMC (ND Ca). It can be similarly effective in providing individual notice to absent class members who may be identified. Doing so, however, may require employing a qualified expert to assist in planning such a notice program. See, e.g., Kaufman v. Am. Exp. Travel Related Servs. Inc., 283 F.R.D. 404 (“In order to find the ‘best practicable notice’ as rule 23 requires, your own expert report may be advisable”). And of course, the qualifications of the expert as well as the validity of his or her conclusions would have to comport with the requirements of Federal Rule of Evidence 702.

An even more direct form of electronic notice can be provided through certain opt-in apps as this type of communication is deterministic, meaning one can tell not only the identity of the recipient but also whether a message was received. For these reasons integration of quantifiable and deterministic “electronic” forms of notice will likely become critical components of individual notice programs in future class actions. Apps are self-contained software programs that users voluntarily download on their phones or other devices. Companies develop apps to make the acquisition of products, services or information easier, such as banking, booking flights, or ordering a prescription. With the right software, an app can have a voice and provide messages directly to an individual when the individual uses the app or even in a locked screen. A program involving notice through the use of an app has already been approved. See Declaration of Cameron Azari re: Kelley v Microsoft Corporation, Case No. C-07-0475 W.D Wash. at Seattle (2008), available at http://blog.seatlepi.com/Microsoft/files/library/vistacapable_one.pdf. In that case, individual notice was provided through a Microsoft Windows Update Program, which caused a pop-up screen to appear on class member computers when they connected to the Internet. And as the Internet of Things becomes more pervasive, “It’s not beyond the realm of possibility to imagine someone’s fridge sending them an email (or a push message, if the app designer is clever) to buy milk and bacon on the way home.” Chad White (ed.), Email Marketing in 2020: 20 Experts Share Their Visions of the Future of the Channel, litmus, 58 https://litmus.com/lp/email-marketing-in-2020.

Conclusion

Transformative and continuing changes in communication media environments should guide contemporary notice programs. The obligation to provide “the best notice that is practicable under the circumstances” presents obvious challenges given that as technology changes, the public’s preferences about how it receives information also changes. As discussed in this article, American consumers do not use communications media or their devices in a homogenous way. Indeed there exist multiple generations of consumers who engage with various media in different ways, and these differences must be considered to formulate modern notice programs that will continue to pass Constitutional muster and meet rule 23’s notice requirements. As the American Consumer’s media preferences change, notice programs will also need to keep pace.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.