On December 1, 2003, Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 (Rule 23

Notice expert Dr. Shannon R. Wheatman and legal writing expert Dr. Terri R. LeClercq, who both worked with the FJC to develop the model notices, illustrate the continuing problems with poorly worded and poorly designed notices in this article.

While notice has progressed in the years since the passage of the plain language amendment, it still has a long way to go to realize the Advisory Committee’s goals that “notice be couched in plain, easily understood language” and practitioners “work unremittingly at the difficult task of communicating with class members.”

What Is Plain Language,

and Why Is It Necessary?

Plain language is clear and direct. It relies on principles of clarity, organization, layout, and design. Plain language writers “let their audience concentrate on the message instead of being distracted by complicated language.”

http://www.plainlanguage.gov/whatisPL/definitions/eagleson.cfm (last visited May 14, 2011).

, 2 (Jan. 2009), available at

http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p20-560.pdf (last visited May 14, 2011).

http://www.nces.ed.gov/Pubs2007/2007480.pdf (finding 13% of adults demonstrated ability to perform such skills, last visited May 14, 2011).

Empirical research has shown that redrafting legal documents into plain language increases reader comprehension and is more persuasive.

ee generally Robert Charrow & Veda Charrow, Making Legal Language Understandable: A Psycholinguistic Study of Jury Instructions, 79 Colum. L. Rev. 1306 (1979) (arguing that systematic rewriting of jury instructions can measurably increase reader comprehension); Veda Charrow, Readability vs. Comprehensibility: A Case Study in Improving a Real Document, in Linguistic Complexity and Text Comprehension: Readability Issues Reconsidered 85 (Alice Davison & Georgia M. Green eds., 1988) (rewriting automobile recall letters for readability increases comprehension among study sample); Michael Masson & Mary Ann Waldron, Comprehension of Legal Contracts by Non-experts: Effectiveness of Plain Language Redrafting, 8 App

lied

Cognitive Psychol. 67 (1994) (reporting enhanced comprehension of legal documents after three stages of simplification).

http://www.impact-information.com/impactinfo/readability02.pdf (“When texts exceed the reading ability of readers, they usually stop reading,” last visited May 14, 2011).

Development of the Model

Plain Language Notices

The FJC conducted research to determine the best way to write class action notices to allow class members to easily understand all of their rights and options. The model plain language notices (“model notices”) include examples for two settlement classes (a securities settlement and a personal injury/product liability settlement) as well as a model notice for an unrestricted certification involving an employment case on a trial track. To support judges and practitioners in these efforts, the FJC has posted the model notices at www.fjc.gov.

The model notices were not created in a vacuum, but were developed through a thoughtful, multi-stage process that culminated with an empirical study. An empirical study on the FJC’s securities notice proved that the plain language versions of the model notices were exponentially more understandable than the typical legalistic notices that are still common today.

Most of the focus group participants displayed only a general knowledge of class action lawsuits

.

C

enter, available at

http://www.fjc.gov/public/home.nsf/autoframe?openform&url_l=/public/home.nsf/inavgeneral?openpage&url_r=/public/home.nsf/pages/816 (last visited May 14, 2010).

Where Are We Now?

With the passage of the plain language amendment, the hope was that the world of class action notice would be turned on its head and lawyers would take great strides to ensure that class members could finally understand all of their rights and options. The real question is: how far has class action notice come in the past six years? If you turn the page of many major newspapers and periodicals, you will probably find a typical class action notice—that is, if you can see it. Many notices continue to be written in small, fine print that is difficult to read.

Current Study

To determine empirically whether class action notices are complying with the plain language requirement of Rule 23, the authors reviewed 511 class action notices published between 2004 and 2009.

Austin American Statesman, Better Homes & Gardens, Cosmopolitan, The Detroit News, Financial Times, Jet, National Geographic, Newsweek, The North Penn Reporter, Oakland Tribune, Parade, People, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Reader’s Digest, Spirit Flight, Sports Illustrated, The Sunday Voice, TV Guide, USA Today, USA Weekend, The Wall Street Journal, and The Wall Street Journal Sunday.

Both authors evaluated the content of each notice.

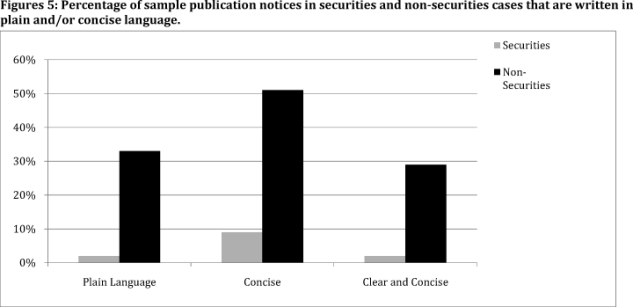

The authors found significant differences in securities and non-securities notices and therefore present the overall findings for each group separately in the sections that follow.

Overall Findings

While the differences in securities and non-securities notices will be detailed below, the authors also found shared challenges with the structure, content, and language of notices that undermined their effectiveness. These common issues led the authors to conclude that lessons drawn from the examples outlined below can be applied more broadly across all types of cases—at both the state and federal levels.

Key Findings

• Most notices did not include an eye-catching and informative headline to capture the attention of potential class members.

• Over 90% of securities notices used an uninformative case caption in the header of the notice.

• Over 60% of notices were written in less than an 8-point font.

• The majority of notices failed to clearly inform class members of the binding effect of the settlement.

• Over two-thirds of the notices with an opt-out right did not inform the class member that they could opt out of the litigation or settlement.

• Over 75% of the notices did not tell class members they had the right to appear through an attorney.

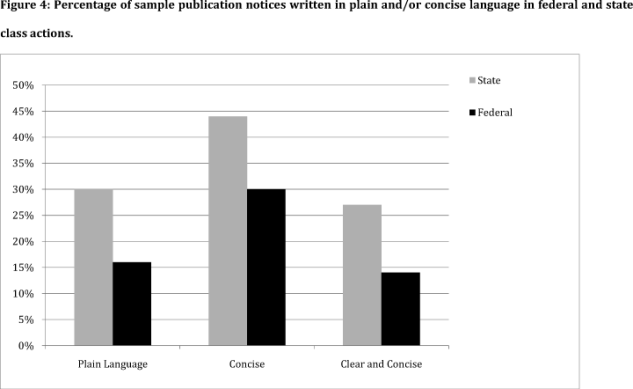

• Over two-thirds of the notices failed to satisfy the concise, plain language requirement of Rule 23.

Notice Design

There is more to a notice than just words on a page. The design or layout of a notice influences readability. The FJC study found that comprehension of class action notices could be significantly improved through deliberate changes in “language, organizational structure, formatting, and presentation of the notice.”

The design of a notice will determine whether anyone will even attempt to read it. The notice must be designed using a reader-friendly format that will entice class members to want to take time to review it. A well-designed notice will incorporate readable fonts, a noticeable and informative headline, section headings, adequate white space, and proper highlighting techniques such as using bold headlines and avoiding all capital letters (CAPs).

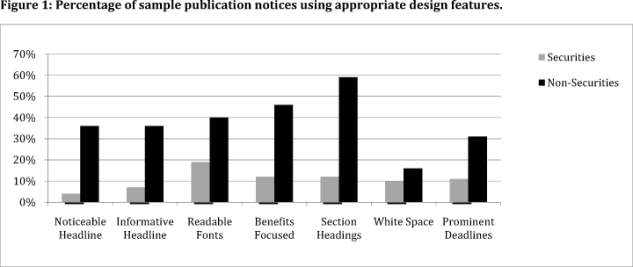

Figure 1 reveals that a clear majority of class action notices in the study did not heed the advice of The Manual for Co

mplex Litigation, which recommends that an author take steps to capture the attention of class members: “Published notice should be designed to catch the attention of the class members to whom it applies. … Headlines and formatting should draw the reader’s attention to key features of the notice.”

Headline

Advertising research has found that the eyes and consciousness of most readers never make it past the headline.

The size of the headline is also important. It is doubtful that attorneys would find it effective to use a tiny font size to advertise their law firm. However, the majority of notices in the study (61% of non-securities and 74% of securities notices) had a headline or heading a few point sizes smaller than the text in this article. Fifty-nine percent of notices used the same size font for the headline and the body of the notice. The headline needs to stand out from the body of the text and should be in a much larger font in order to catch the attention of potential class members. Moreover, a recent study found that an easy-to-read font is more likely to get people to act because it is more appealing, easier to handle, and more efficient.

ogist, 108, 108 (2010) (suggesting that font type leads readers to predict ease or difficulty of reading, informing their decision to act).

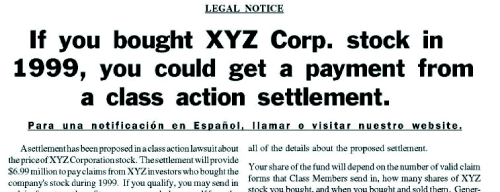

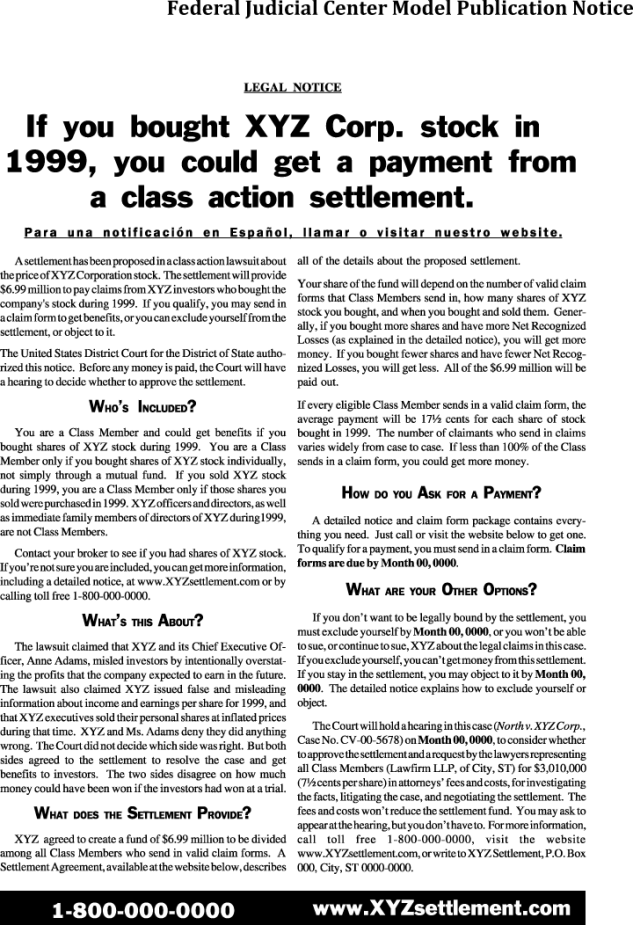

A carefully crafted headline should quickly persuade readers that they have a stake in the class action and that they will be able to understand it. Here is an example of an attention-getting headline from the securities model notice (the actual sized notice appears below):

The large, noticeable font will capture the attention of potential class members, and the benefit focus of the headline will motivate them to read the notice.

Organization, Internal Cues, and White Space

Information is well organized if it is easy for readers to navigate. Writers can accomplish this by using appropriate headings and sub-headings. The notice should tell the story of the litigation. Unnecessarily long sentences and lengthy paragraphs in many of the sample notices became even more cumbersome because they also failed to incorporate section headings (41% of non-securities and 88% of securities notices). Section headings serve as guideposts to the information in each section and improve readability by breaking up large blocks of text.

enter

for Writing (Apr. 11, 2003), available at

http://www.writing.umn.edu/tww/disciplines/business/resources/BA3033headings.html (last visited May 14, 2011).

In addition, a large majority of sample notices (84% of non-securities and 97% of securities notices) included wall-to-wall words with little to no white space around the paragraphs and headings. Focus groups in the FJC study found that level of text density off-putting.

Appropriate Highlighting Techniques

Furthermore, the model notices show that appropriate highlighting of key information (e.g., bolding important deadlines) also breaks up the text and lets readers know what is important. Appropriate highlighting of important information appeared in only one out of 10 securities notices and about one-third of non-securities notices. Another common design flaw is the use of all capital letters in long strings of text. Some writers may mistakenly believe this is a good way to provide a class definition or to give warnings. However, PEOPLE RECOGNIZE WORDS BASED ON THEIR SHAPE, NOT THE ACTUAL LETTERS IN THE WORDS.

: or how I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bauma, Microsoft Corp. (July 2004), available at

http://www.microsoft.com/typography/ctfonts/wordrecognition.aspx.

Content of the Notice

Rule 23 requires that specific content be written in plain language.

“The notice must clearly and concisely state in plain, easily understood language … .”).

;

In re Nissan Motor Corp. Antitrust Litig., 552 F.2d 1088, 1104–05 (5th Cir. 1977) (“Surely ‘the best notice practicable under the circumstances cannot stop with … generalities. It must also contain an adequate description of the proceedings written in objective, neutral terms, that … may be understood by the average absentee class member.” (quoting Robinson v. Union Carbide Corp., 544 F.2d 1258, 1263–65 (5th Cir. 1977))).

The Manual for Complex Litigation also recommends that the notice should: include deadlines for taking action, describe essential terms of the settlement (including information that will allow class members to calculate their benefit), indicate the time and place of the fairness hearing, and prominently display how to get more information.

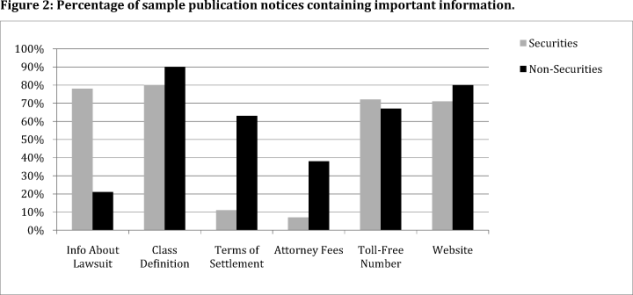

The study revealed that some notices provide so few details that it is unlikely class members would recognize that they might benefit from reading them (Figure 2); it is also unlikely that those class members would learn enough from the information to decide what to do. Most securities notices failed to provide class members with details about the lawsuit, the terms of the settlement, or how much attorneys stand to make from the settlement. Non-securities notices were better on most counts, but the number of notices that did not clearly tell class members what they needed to know was still high. The most astounding finding was that 10% of non-securities notices and 20% of securities notices did not provide a definition of the class.

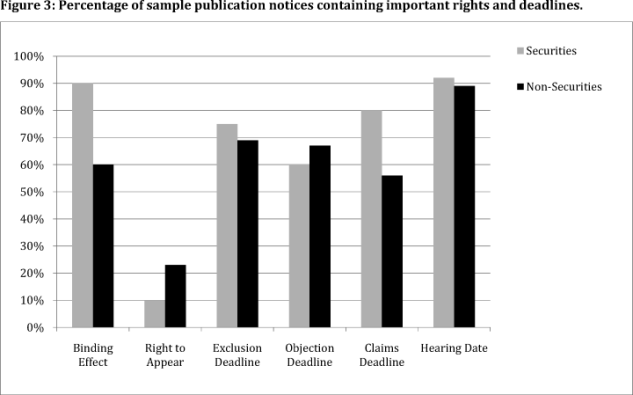

Figure 3 provides even more troubling findings. The basic rights afforded class members under Rule 23 are often omitted from publication notices. The most common omission was notice of the right to appear, which was absent in 77% of non-securities notices and 90% of securities notices. Many notices did not inform class members that they had the right to object to a settlement (33% of non-securities and 40% of securities notices) or that they could opt out of the litigation or settlement (25% of non-securities and 31% of securities notices). Most problematic was that 40% of non-securities notices and 10% of securities notices did not even tell class members the all-important fact that they would be bound by any court order if they remained in the class. In addition, the term “bound” is foreign to most class members. Of those notices that informed class members they would be bound by the court’s decisions, only a handful (31% of non-securities and 14% of securities notices) of properly educated class members, in easily understood language, as to what “bound” really meant. The FJC model notices explain what this means to the class member in practical terms: “If you don’t want to be legally bound by the settlement, you must exclude yourself by Month 00, 0000, or you won’t be able to sue, or continue to sue, XYZ about the legal claims in this case.”

Readability

“The purpose of [readability] is to close the gap between the reading level of the [notice] and the reading ability of [class members].”

Further analysis revealed that the securities cases in the study contributed directly to the disparity between federal and state court notices. Specifically, in non-securities cases, 27% of federal class action notices and 31% of state class action notices were clear and concise. In contrast, a meager 2% of the 170 notices filed in federal securities cases provided class members with a clear, concise recitation of their rights. These findings, albeit not very surprising, seem to provide one explanation of why billions of dollars are left unclaimed in securities cases.

http://www.riskmetrics.com/system/files/private/SCAS_billion-here-billion-there.pdf (last visited May 14, 2010) (“[A]ccording to a series of academic studies conducted over the last decade, as well as anecdotal evidence from market participants, anywhere from 30%–70% of investors that are eligible to participate in a given settlement fail to file a claim form … .”).

Plain language is attainable by reducing or eliminating writing that frustrates even the most motivated readers: legal jargon, unfamiliar or abstract words, negatively modified sentences, words with double meanings, verbs as nouns, misplaced phrases, and prepositional phrases.

Inc., Plain Language Primer for Class Action Notice 1, 11–12, available at

http://www.kinsellamedia.com/portals/1/media/pdf/PlainLanguagePrimer.pdf (last visited May 14, 2010).

It is important for practitioners to keep in mind that a notice needs only to meet the content requirements of Rule 23; it is not necessary to include every detail from the class action complaint or settlement agreement. Two legal commentators understood this concept quite well when they remarked that “[m]uch of what lawyers write … including many class action notices, is incomprehensible to average citizens. The lawyerly concern for completeness and accuracy may conflict with the objective of intelligibility.”

Many practitioners may believe that it is not necessary to meet the requirements of Rule 23 in a publication notice because that information can be found in a more detailed notice. The authors disagree, but nonetheless reviewed 50 long form notices (16 securities, 34 non-securities) that were filed in 2008 and 2009. These long form notices suffered from the same defects as the publication notices. Many lacked a readable headline, few clearly informed class members about their rights, and most would be unintelligible to the average layperson. The majority of long form notices were as poorly written as the publication notices—only 18% satisfied the concise, plain language requirement (26% of non-securities notices and none of the securities notices).

A few findings from the FJC study are important to note here. Some securities practitioners mistakenly believe that a simple notice is not necessary for an educated class. The study on the FJC’s securities notices found that even shareholders were less likely to understand a legalistic class action notice than a plain language notice.

d. at 44 (finding that only 2% of shareholder participants would read a legalistic notice carefully whereas 57% reported they would carefully read a plain language notice).

Keeping It Readable

Documents with legal content should not be burdensome reading to their intended audience. Writers should assume that class action notices will be read by a variety of consumers who shop, buy, work, and live their lives without needing to know court names and case numbers. When writers choose their words, they need to focus on common equivalents of legal jargon. Most readers will stop reading “a claim for declaratory relief” before they learn that “relief” was indeed their goal. If a legal or technical term is necessary, it needs to be defined: “exclusion means … .”

Plain language is more than merely simple words; embedded in the term is sentence length, subject/verb order, unambiguous modifiers, and even the active voice. Rule 23 is not asking authors to talk down to the reader, but it does insist that the notice be stated in “plain, easily understood language.”

A notice needs to be clear and succinct, so an average reader can go through it once and understand its general message. Few readers will take the time to re-read a legal notice that appears inside their newspaper or magazine. Potential class members should be caught up by the headline and mention of the product and then able to grasp the point of the notice at first glance. If not, writers of the notice have disregarded the purpose of the notice—to inform class members about the rights and options they have in the case.

Conclusion

No one can affect class action notice as effectively as the judges who prove or reject them. Judges must be the standard-bearers and stringently enforce Rule 23’s requirements. Attorneys and judges can use the FJC model notices as templates or outlines, which demonstrate that it is possible to get all of the necessary information into a noticeable, succinct, plain language format. Satisfying Rule 23 protects the interests of the class and strengthens the class action device, in addition to better serving the principle of due process. With the active participation of judges and practitioners, and widespread use of the FJC models and the attached checklist (see Table A, above), the task of effectively communicating with class members can be made easier.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.