Part 1. Introduction

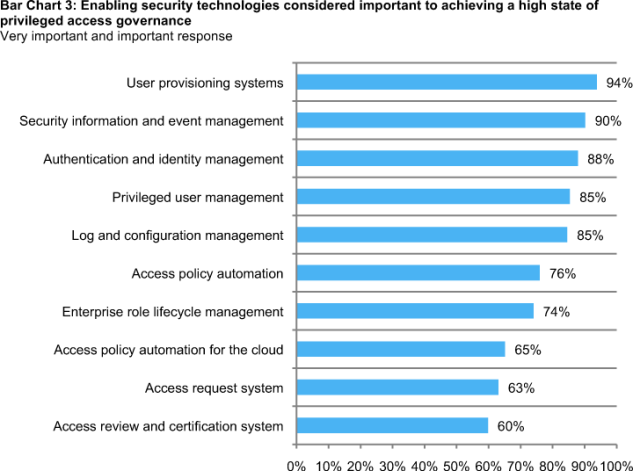

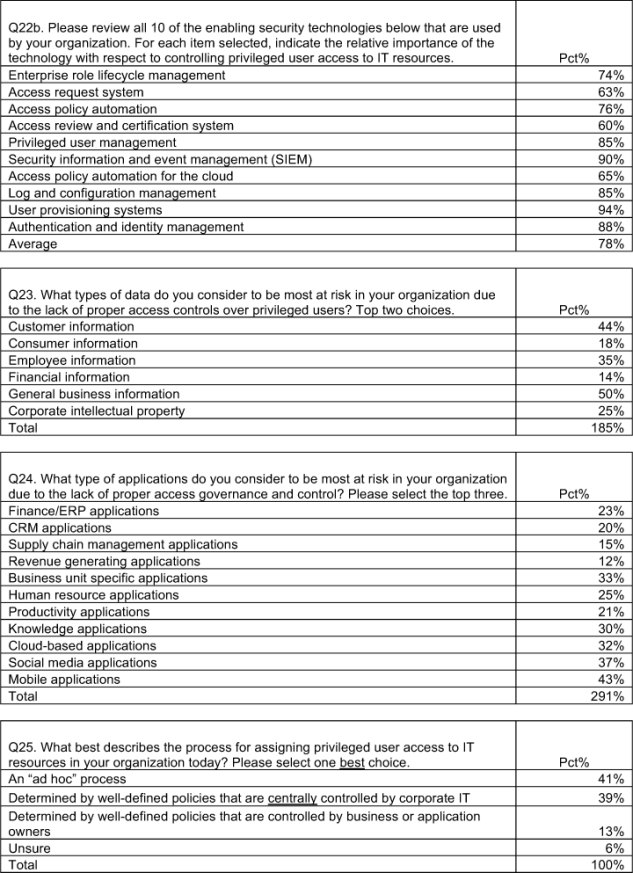

Ponemon Institute is pleased to present the findings of The Insecurity of Privileged Users sponsored by HP Enterprise Security. The purpose of this research is to understand the current threats to an organization’s sensitive and confidential data created by a lack of control and oversight of privileged users in the workplace. User provisioning systems and security information and event management (SIEM) are currently considered the most important technologies used to control privileged user access to information technology resources.

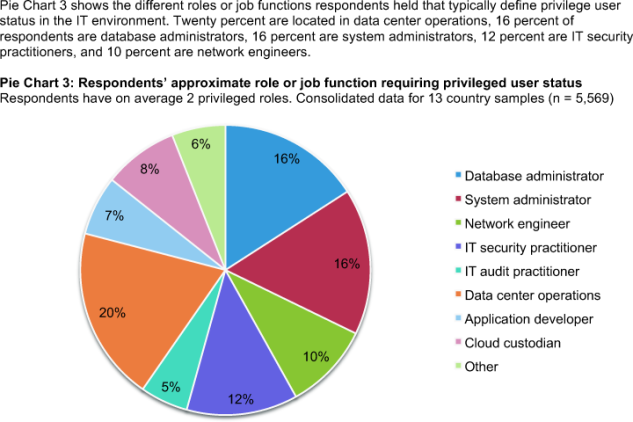

For purposes of this research, privileged users include database administrators, network engineers, IT security practitioners and cloud custodians. According to the findings of this study, these individuals often use their rights inappropriately, putting their organizations’ sensitive information at risk. For example, the majority of respondents say privileged users feel empowered to access all the information they can view and although not necessary will look at an organization’s most confidential information out of curiosity.

We believe respondents have a deep understanding of the potential risks to sensitive data because they have privileged access in their organizations. For purposes of this research, we surveyed 5,569 IT operations and security managers in the following 13 countries: United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Singapore, Hong Kong, Korea, Japan, India, Australia and Brazil.

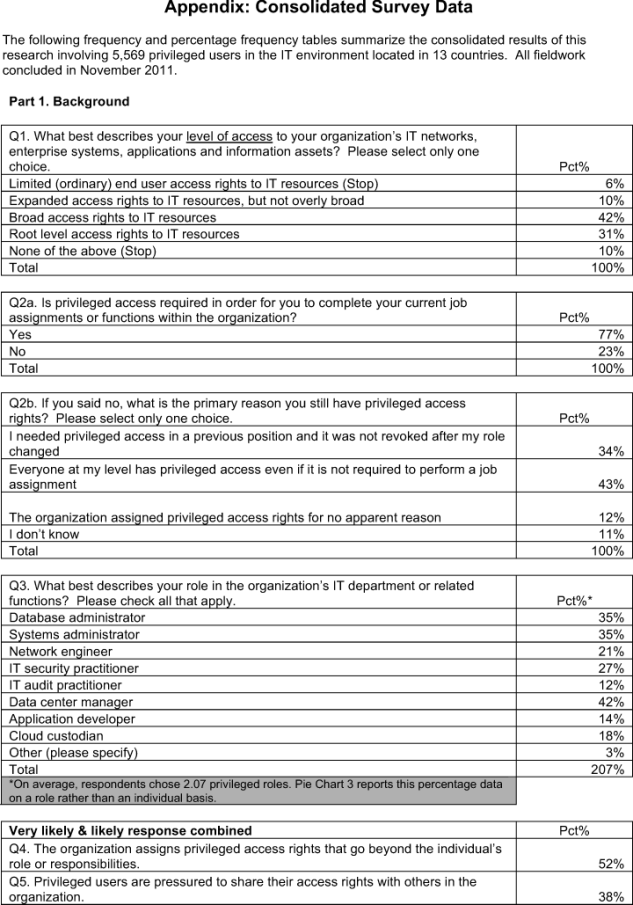

To ensure that respondents have an in-depth knowledge of how their organizations are managing privileged users, we asked respondents to indicate their level of access to their organizations’ IT networks, enterprise systems, applications and information assets. If they had only limited end user access rights to IT resources, they were not included in the final sample of respondents.

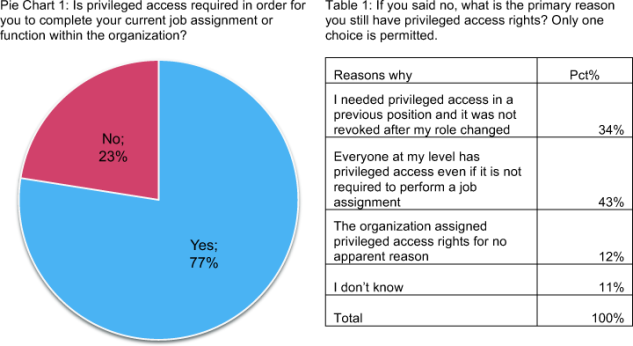

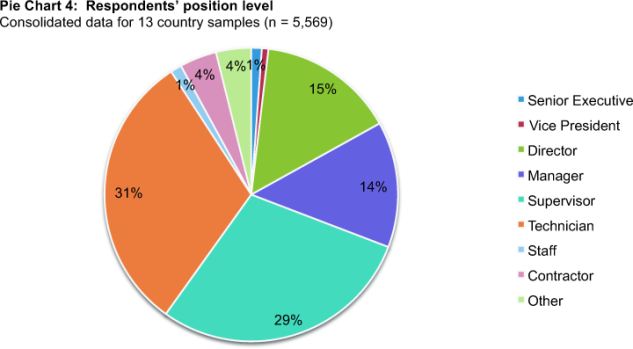

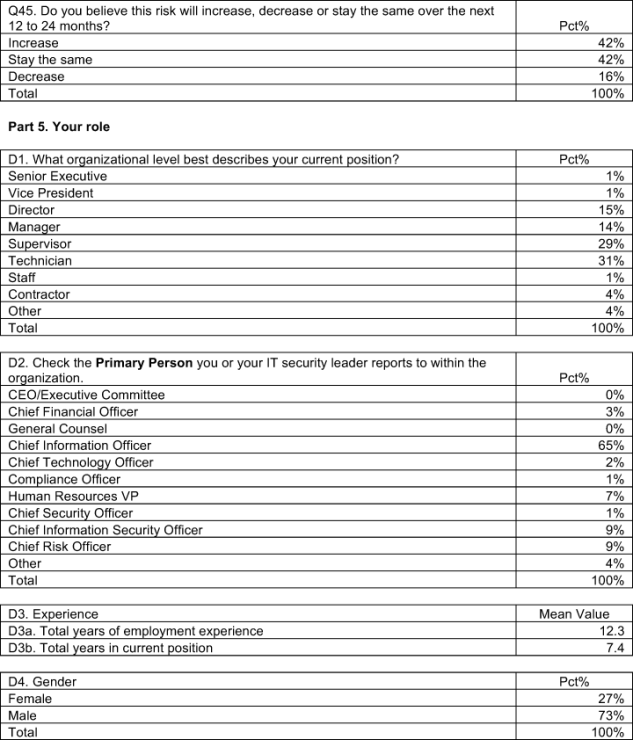

Sixty percent of respondents are at the supervisor level or higher, and most report to the chief information officer. On average, respondents have been employed in their current position for slightly more than 7 years. According to 77 percent of respondents, privileged access rights are required to complete their current job assignment. However, 23 percent say the access rights they have are not necessary for their role.

The following practices occur in many of the global organizations represented in this study:

- Not revoking privileged access status after the employee’s role changed and providing everyone at a certain level in the organization with such access.

- IT operations are primarily responsible for assigning, managing and controlling privileged user access rights. However, business units and IT security are the functions most often responsible for conducting privileged user role certification.

- Rarely are requests for privileged access immediately checked against security policies before access is approved and assigned.

- Privileged access rights that go beyond the individual’s role or responsibilities are often assigned.

- Commercial off-the-shelf automated solutions are most often used for granting privileged user access to IT resources and for reviewing and certifying privileged users’ access.

- There is an inability to create a unified view of privileged user access across the enterprise.

Part 2. Key Findings

Following is a summary of the consolidated global key findings. The major topics addressed in this study are: privileged user access governance, the process for assigning privileged user access to IT resources, and critical success factors and barriers to reducing the risks of an insecure privileged user access program.

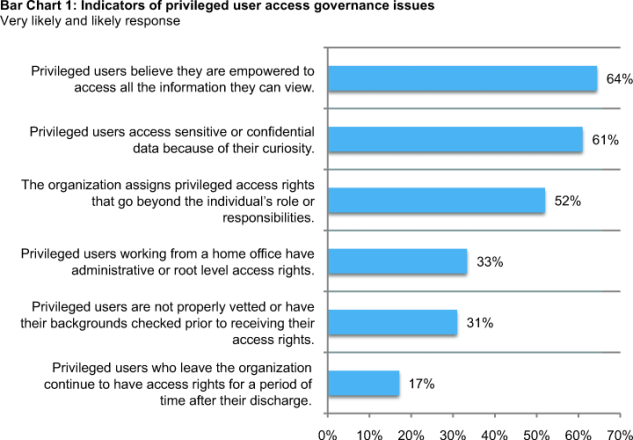

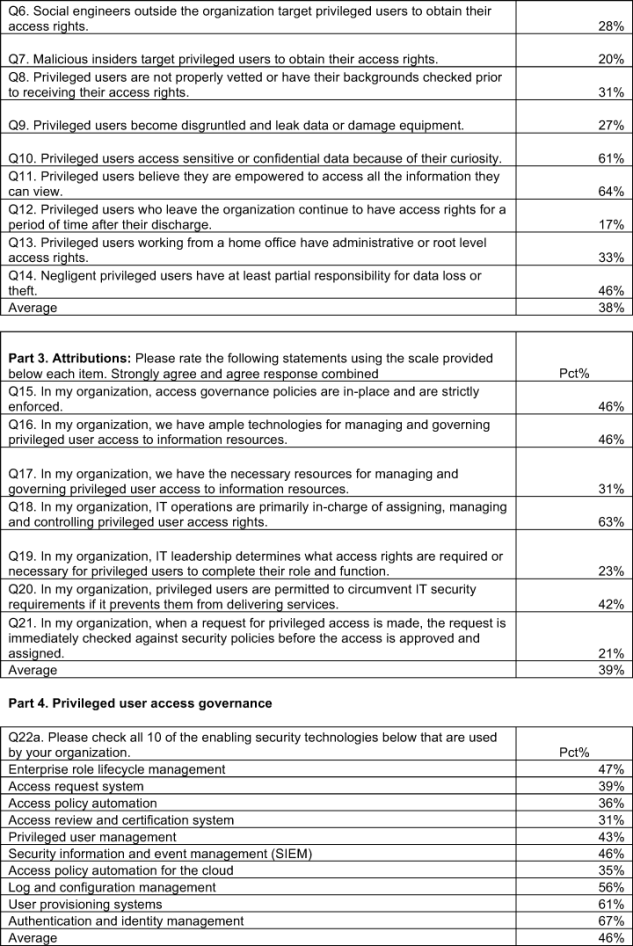

Privileged user access is often abused. The detailed findings section of this paper presents the perceptions respondents have about the management of privilege user access and common practices of privileged users. According to 64 percent of respondents, it is very likely or likely that privileged users believe they are empowered to access all they information they can view, and a similar percentage (61 percent) say privileged users access sensitive or confidential data because of their curiosity.

As an indication that a governance problem exists in many organizations, 52 percent of respondents say it is likely or very likely that the organization will assign privileged access rights that go beyond the individual’s role and responsibilities. However, organizations in this study seem to do a better job at making sure employees who leave the organization do not continue to have their access rights. Only 17 percent say this is very likely or likely to happen.

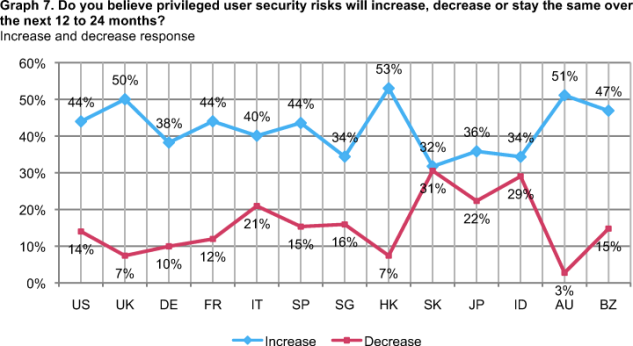

What’s at risk? Forty-two percent of respondents say the risk to organizations caused by the insecurity of privilege access users will increase over the next 12 to 24 months, and 42 percent say it will stay the same. Cloud-based applications, virtualization and regulations or industry mandates are the primary reasons for this belief.

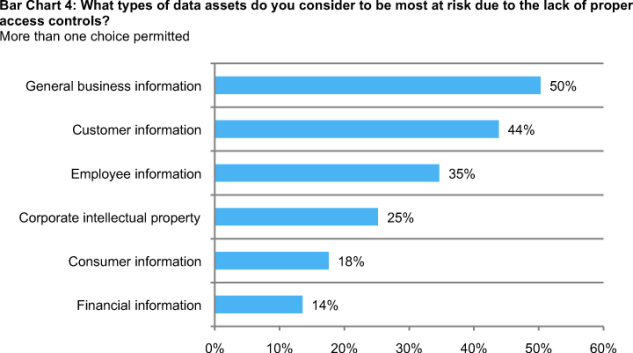

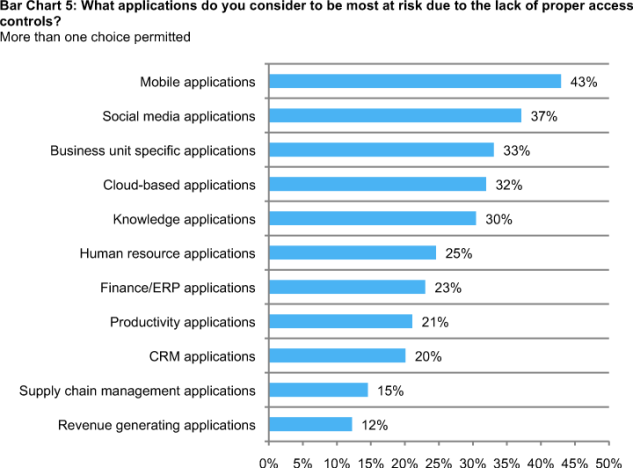

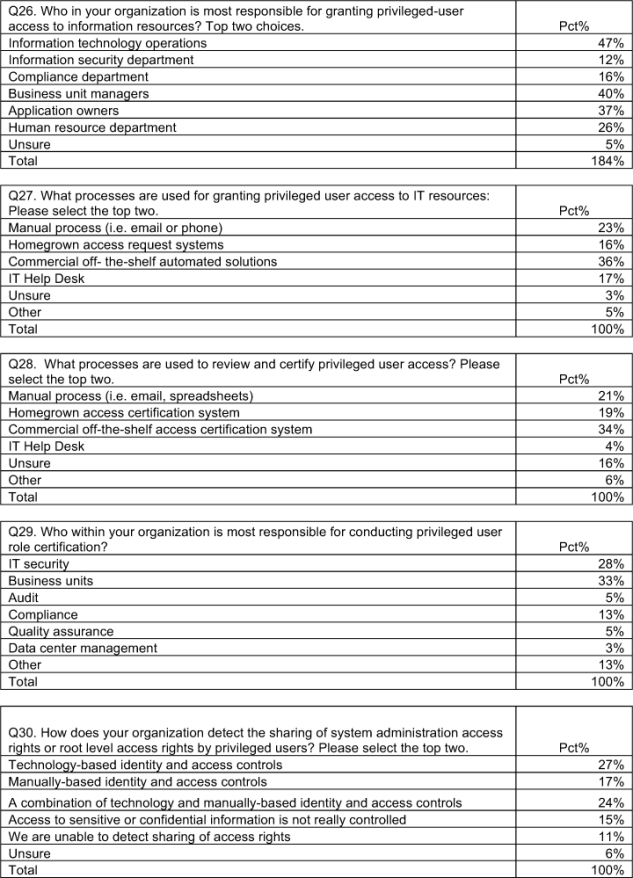

General business information followed by customer information are the data types at risk if there is a lack of proper access controls over privileged users, and the applications most threatened are mobile, social media and business unit specific applications.

User provisioning systems and SIEM are the preferred technologies. When asked to indicate the relative importance of technologies with respect to controlling privileged user access to IT resources, the following were selected: user provisioning systems and security information and event management systems (SIEM) and authentication and identity management.

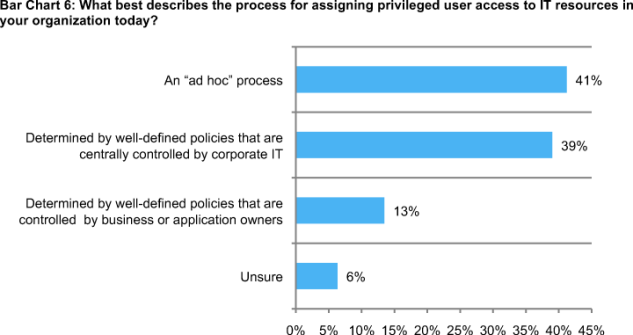

Many organizations do have well-defined policies for assigning privileged user access. While 41 percent say the best way to describe the assigning of privileged user access to IT resources is ad hoc, 39 percent say assignment is determined by well-defined policies that are centrally controlled by corporate IT and another 13 percent say it is determined by well-defined policies that are controlled by business or application owners.

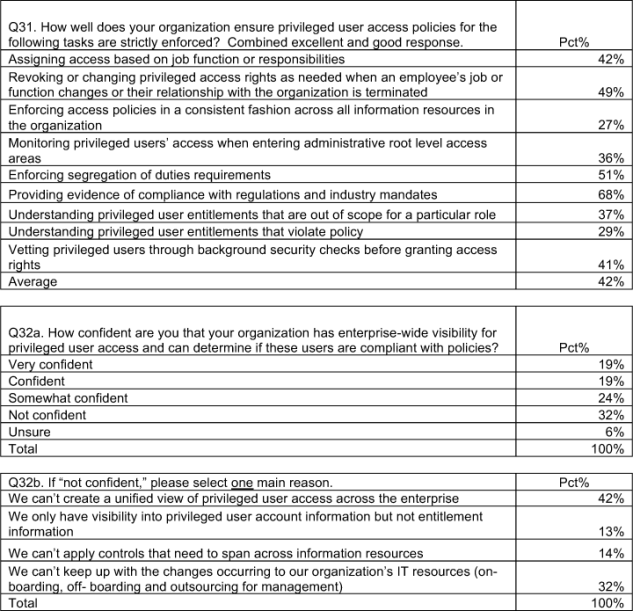

Forty-seven percent say information technology is responsible for granting privileged user access to information resources, and 40 percent say it is the business unit manager. Most responsible for conducting privileged user role certification are business units (33 percent) and IT security (28 percent).

Commercial off-the-shelf automated solutions are most often used for granting privileged users access to IT resources and for reviewing and certifying privileged users’ access.

Many organizations face a lack of enterprise visibility of access rights making governance difficult.

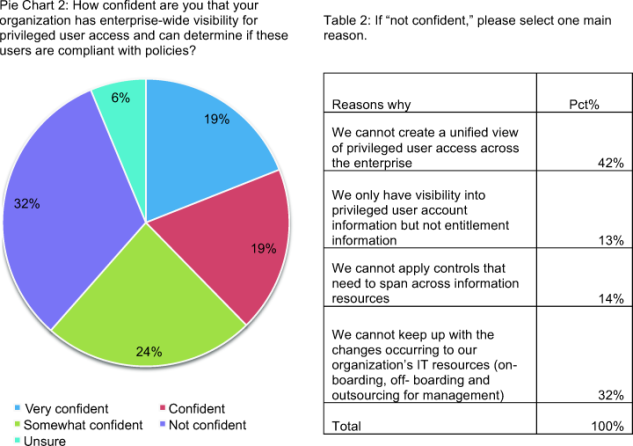

Almost one-third (32 percent) of respondents are not confident and six percent are unsure that their organization has enterprise-wide visibility for privilege user access and can determine if these users are compliant with policies. The primary reason for this lack of confidence is the inability to create a unified view of privileged user access across the enterprise.

Twenty-seven percent say their organizations use technology-based identity and access controls to detect the sharing of system administration access rights or root level access rights by privileged users, and 24 percent say they use a combination of technology and manually-based identity and access controls. However, 15 percent admit access is not really controlled, and 11 percent say they are unable to detect sharing of access rights.

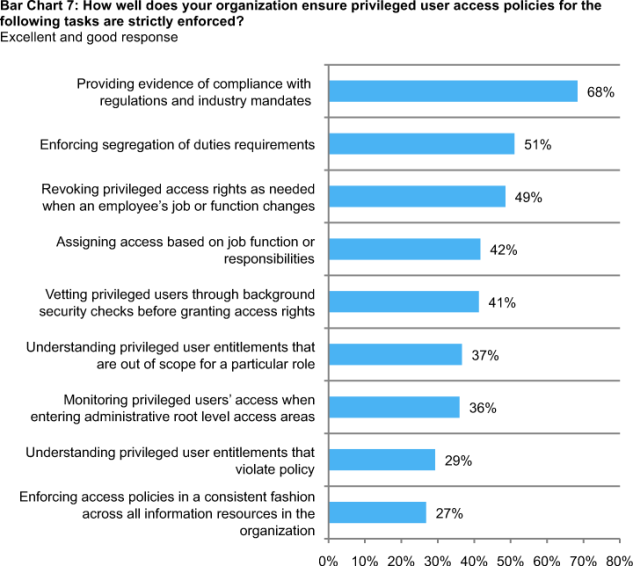

What organizations say they do well is to provide evidence of compliance with regulations and industry. Areas where organizations most need to improve include: monitoring privileged users’ access when entering administrative root level access, understanding privileged users entitlements that violate policy and enforcing access policies in a consistent fashion across all information resources in an organization.

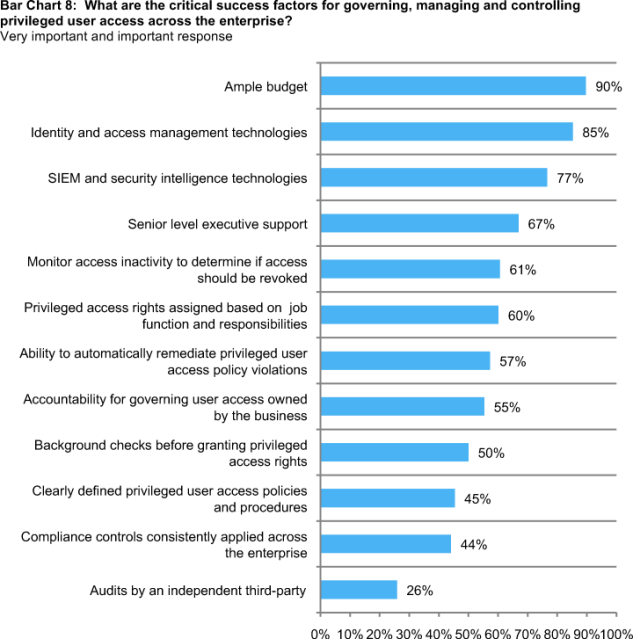

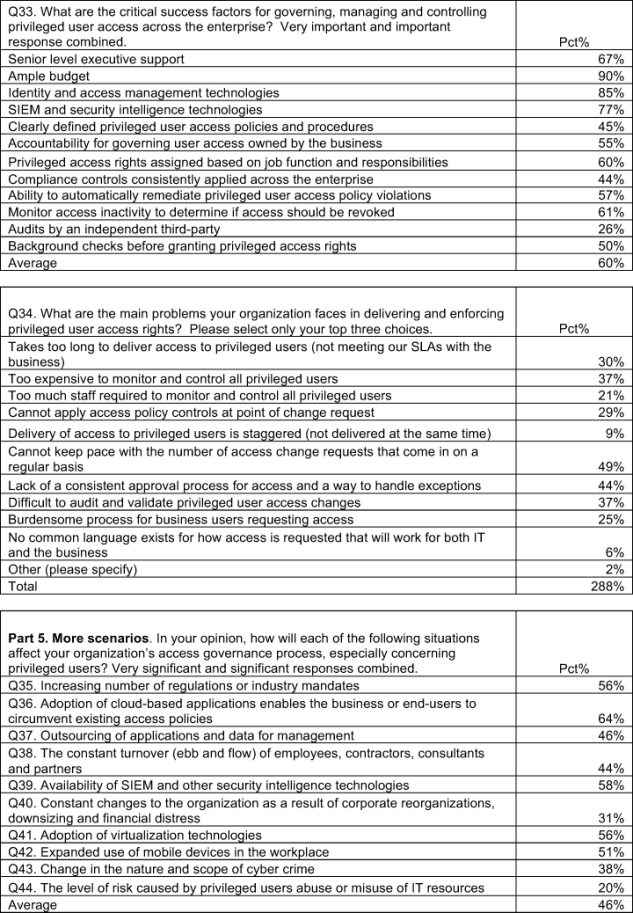

The critical success factors. Budget, identity and access management technologies and security intelligence technologies are the three most critical success factors for governing, managing and controlling privileged user access across the enterprise. Least critical is audits by an independent third party.

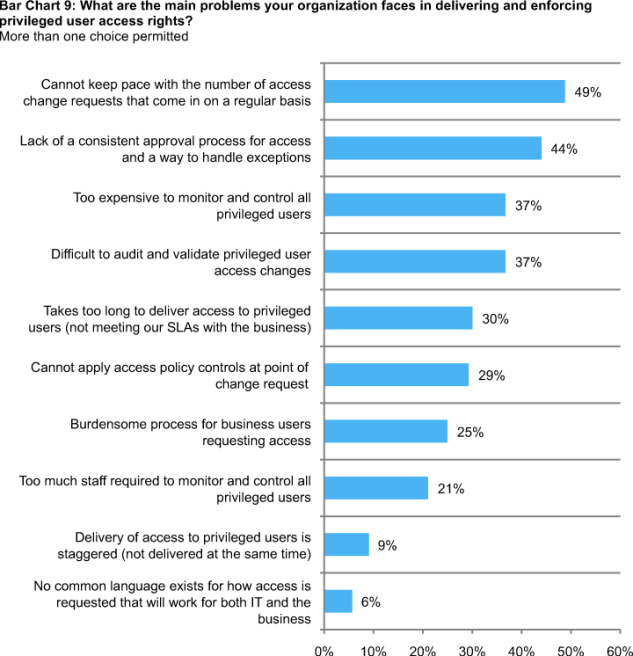

The barriers to delivering and enforcing privileged user access rights. The top barriers are: cannot keep pace with the number of access change requests that come in on a regular basis, lack of a consistent approval process for access and a way to handle exceptions, too expensive to monitor and control all privileged users and difficult to audit and validate privileged user access changes.

The following are believed to have a very significant or significant effect on privileged user access governance: adoption of cloud-based applications enables the business or end-users to circumvent existing access policies, availability of SIEM and other network technologies, adoption of virtualization technologies and increasing number of regulations.

Global Perspective

The potential for privileged access abuse seems greatest in France, Italy and Hong Kong, according to respondents in those countries. Seventy-nine percent of respondents in France say privileged users believe they are empowered to access all the information they can view followed by 76 percent of respondents in Italy and 74 percent of respondents in Hong Kong. The countries where this is less likely to occur, according to respondents, are Japan, Singapore and Germany.

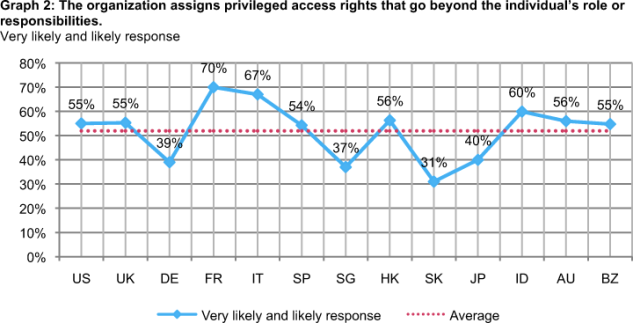

The countries where privileged users are most likely to access sensitive or confidential data because of their curiosity are France, Australia and Italy. Less likely are Japan, Singapore and Germany. Also in France and Italy, according to respondents, organizations are most likely to assign privileged access rights that go beyond the individual’s role or responsibilities. This is less likely to occur in Korea, Singapore and Germany.

Respondents in the United Kingdom, Hong Kong and Australia are more concerned that the risk to an organization’s access governance process will increase. Countries that are more optimistic about the risk are Korea, India and Singapore.

The situations that are most likely to affect their organizations’ access governance process, especially for privileged users are: adoption of cloud-based applications because it enables the business or end-users to circumvent existing access policies, availability of SIEM and other security intelligence technologies, increasing number of regulations or industry mandates and adoption of virtualization technologies. Only the United States, Germany and France selected the change in the nature and scope of cybercrime as a major influence on access governance procedures.

Part 3. Implications and Recommendations

The findings reveal a plethora of security problems caused by privileged access abuse. We believe enabling technologies are essential to identifying threats posed by negligence and malicious acts. We also recommend the following practices:

- Implement a well-managed enterprise-wide privileged user access governance process that is based on roles and responsibilities. Manage changes to a privileged user’s role to ensure that he or she continues to have the correct access rights for a given job function.

- Create well-defined business policies for the assignment of access rights. These policies should be centrally controlled to ensure they are enforced in a consistent fashion across the entire enterprise.

- Understand how to make the case for building an enterprise-wide privileged user access governance process to senior management. Factors to include are the fines and penalties for noncompliance and downtime as a result of negligence that causes operational problems. With respect to data breaches, it is the cost of notification, customer attrition and loss of reputation that can severely impact an organization’s bottom line. This will help ensure there is an ample budget and collaboration among business units to enforce privileged user access policies.

- Track and measure your organization’s ability to enforce privileged user access policies. This includes its effectiveness in managing changes to users’ roles, revoking access rights upon an individual’s termination, monitoring access rights of privileged users’ accounts and monitoring segregation of duties.

- Ensure that accountability for privileged users access rights is assigned to the business unit that has domain knowledge of the users’ role and responsibility.

- Become proactive in managing access rights. Instead of making decisions on an ad hoc basis based on decentralized procedures, build a process that enables your organization to have visibility to all user access across all information resources and entitlements to these resources. Technologies that automate access authorization, review and certification will limit the risk of human error and negligence.

Part 4. Detailed Findings

The majority of respondents (77 percent) say privileged user access rights are necessary for fulfilling their job function or role (see Pie Chart 1). Twenty-three percent say they have these rights even though they are not necessary for their work. As shown in Table 1, 43 percent of these respondents believe they still have this privilege because of their position. Another 34 percent say privilege access, while once necessary, was not revoked after their role changed.

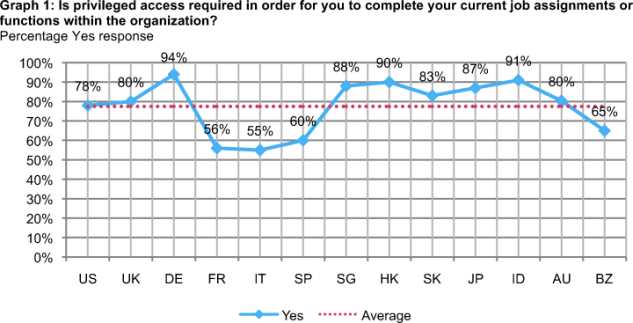

The need for privileged access rights varies among respondents in 13 countries. As shown in Graph 1, 94 percent of respondents in Germany say privileged access is essential. In contrast, only 55 percent of Italian respondents believe this to be so.

Respondents were asked to assess the likelihood of certain scenarios occurring in their organizations. The most likely scenario to occur, according to 64 percent of respondents, is that privileged users believe they are empowered to access all the information they can view. Sixty-one percent believe privileged users are very likely or likely to view sensitive or confidential data simply because they are curious. Similarly, 52 percent believe privileged users within their organization have access rights that go beyond their role or job-related responsibilities.

Do privilege access rights go beyond job role or function? In other words, is access governance too lenient and as a result puts information assets at risk? As shown in Graph 2, more than 70 percent of respondents in France and 67 percent of respondents in Italy believe privilege access rights within their organization go beyond role and function. In contrast, 31 percent of respondents in Korea and 37 percent of respondents in Singapore believe privilege access rights are too pervasive.

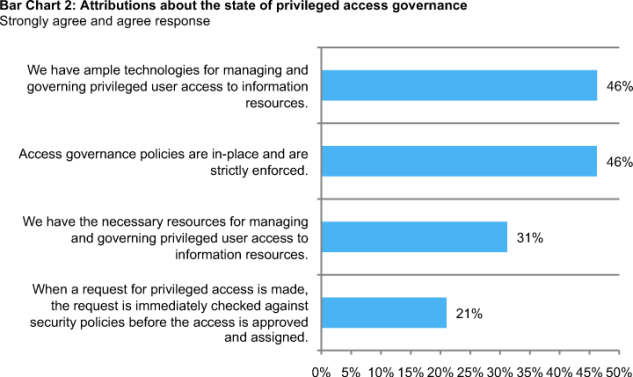

Bar Chart 2 reports four attributions about the state of access governance within respondents’ organizations. Each percentage reflects the strongly agree and agree response combined. Hence, a percentage greater than 50 percent suggests a net-favorable response. Inversely, a percentage below 50 percent suggests a net-unfavorable response. All four attributions in this chart are below 50 percent suggesting a net-unfavorable view about access governance in the organizations studied.

Only 21 percent strongly agree or agree that requests for privileged user access are immediately checked against security policies before the access is approved and assigned. Thirty-one percent strongly agree or agree that their organizations have the necessary resources for managing and governing privileged user access to information assets. Forty-six percent believe their organizations have policies that are strictly enforced. The same percentage of respondents believe their organizations have ample enabling technologies available for managing privileged user access to information resources.

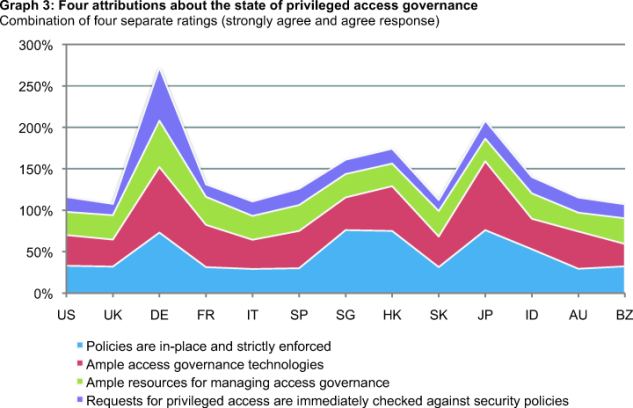

Graph 3 presents an area diagram showing respondents’ strongly agree and agree ratings to four attributions about the state of privileged access governance within their organizations. A high combined score suggests a stronger access governance regime, and a low combined score suggests the opposite. This graph shows Germany achieves the highest combined score followed by Japan. In contrast, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Korea, Italy, United States and Australia have much lower combined scores.

Respondents were asked to select the technologies presently used within their organizations. They then rated each security technology based on its importance in governing and controlling privileged user access to data assets and other IT resources. The combined very important and important ratings are reported in Bar Chart 3. As shown, the top three technologies rated by respondents as most important are: user provisioning (94 percent), security information and event management or SIEM (90 percent), and authentication and identity management (88 percent).

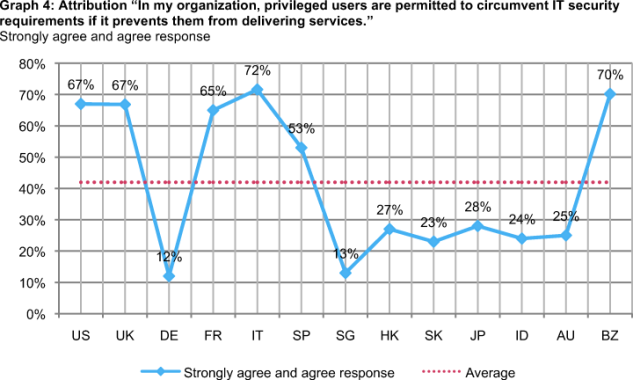

Graph 4 reports respondents’ rating of an attribution dealing with a potentially dangerous practice—namely, the privileged user’s ability to circumvent IT security requirements in order to deliver services. Clearly, there are significant differences among the 13 countries studied. On the positive side, Germany (12 percent) and Singapore (13 percent) report the lowest ratings of this attribution. In sharp contrast, respondents in Italy (72 percent) and Brazil (70 percent) report the highest ratings. These results suggest the circumvention of IT security requirements may be a pervasive practice in Italy, Brazil and in several other countries.

Bar Chart 4 shows the data assets most at risk, according to respondents. As shown, general business information (such as documents, spreadsheets, e-mails and other sources of unstructured data) are considered most at risk because of improper access controls. Customer and employee information are also viewed as high-risk data assets. Financial information is viewed as the least at risk. This finding, at least in part, may be due to access requirements implemented over the past several years in response to regulatory requirements such as Sarbanes-Oxley, Basil II and other comparable standards.

Bar Chart 5 reports the applications most at risk, according to respondents. Mobile applications and social media present the applications with the highest levels of risk because of improper access controls. Business unit specific and cloud-based applications are also viewed as high-risk.

Respondents were asked to define their organization’s process for assigning privilege user access. As shown in Bar Chart 6, 41 percent of respondents say the process is ad hoc. Another 39 percent define their organization’s process as based upon well-defined policies and centrally controlled by corporate IT.

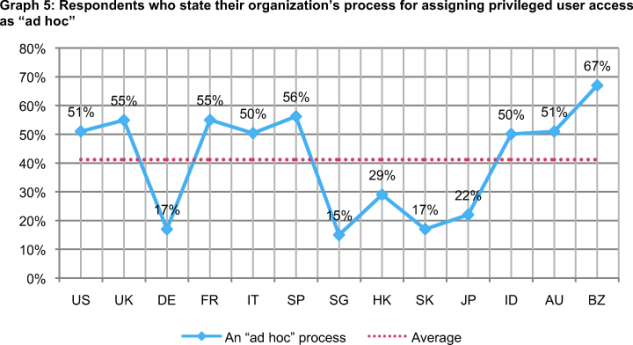

Graph 5 reports the percentage frequency of respondents within each country that say their organization’s process for assigning privileged access is ad hoc. As shown, Singapore (15 percent), Korea (17 percent) and Germany (17 percent) are least likely to define this process as ad hoc. In contrast, respondents in Brazil (67 percent) are most likely to see their organization’s process for assigning privileged access as ad hoc.

Bar Chart 7 provides respondent ratings to a list of best practices. Each rating is defined as the combination of an excellent and good response. A high percentage value suggests a favorable result. Accordingly, 68 percent of respondents say their organizations are excellent or good in providing evidence of compliance with regulations and industry mandates. Fifty-one percent say their organizations are excellent or good in enforcing segregation of duties. Only 27 percent of respondents say their organizations enforce access policies in a consistent fashion. Further, only 29 percent say their organizations have an excellent or good understanding of privileged users’ entitlements that violate policy.

Pie Chart 2 shows that only a minority of respondents are very confident (19 percent) or confident (19 percent) that their organizations have enterprise-wide visibility for privileged user access. Table 2 reports the reasons why respondents are not confident. As can be seen, 42 percent say their organizations cannot create a unified view of privileged user access across the enterprise. Another 32 percent say their organizations cannot keep up with the pace of change resulting from on-boarding, off-boarding and outsourcing activities, respectively.

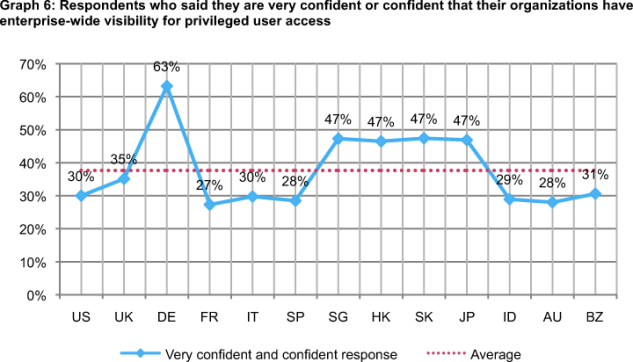

Graph 6 reports the very confident or confident responses for respondents among 13 countries. As reported, German respondents (63 percent) have the highest level of confidence in their organization’s ability to achieve enterprise-wide visibility for privileged user access. Respondents in France (27 percent), Spain (28 percent) and Australia (28 percent) have the lowest levels of confidence.

Bar Chart 8 summarizes respondents’ very important and important ratings to critical success factors relating to privilege user access governance. The top three most important factors are: ample budget (90 percent), identity and access management technologies (85 percent) and SIEM and security intelligence technologies (77 percent). Least important, according to respondents, is third-party audit (26 percent).

Bar Chart 9 summarizes the main issues or problems organizations deal with in the delivery and enforcement of privileged user access rights. The top rated problems include workload (49 percent), lack of a consistent approval process over access rights assignment (44 percent) and cost-related issues (37 percent).

Graph 7 shows respondents generally viewing the risk of privilege user insecurity as either increasing or staying the same. The graph clearly shows that respondents in all countries are more likely to see the risk as increasing versus decreasing. The largest gaps between these two choices include Australia (Diff = 48 percent), Hong Kong (Diff = 46 percent) and the United Kingdom (Diff = 43 percent). The smallest gaps include Korea (Diff = 1 percent) and India (Diff = 5 percent).

Part 6. Methods

Table 3 reports the survey response statistics in 13 countries. All survey results were collected over a two-month period ending in November 2011. Utilizing proprietary sampling methods, we identified 130,791 individuals for possible participation in our global survey about privileged users in the IT environment. All of these individuals held bona fide credentials in the IT or security fields.

A total of 6,309 survey responses were received. After reviewing surveys for reliability and implementing screening criteria, we achieved a final sample of 5,569 respondents. The overall response rate is 4.5 percent. The largest country sample is the United States (n = 558), and the smallest country sample is Hong Kong (n = 319).

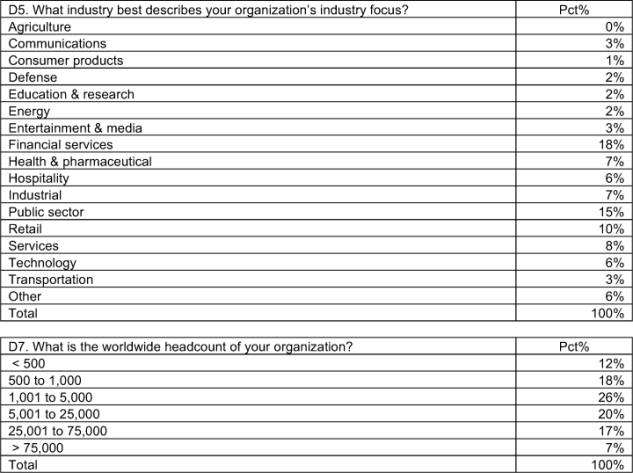

Pie Chart 3 shows the different roles or job functions respondents held that typically define privilege user status in the IT environment. Twenty percent are located in data center operations, 16 percent of respondents are database administrators, 16 percent are system administrators, 12 percent are IT security practitioners, and 10 percent are network engineers.

Pie Chart 4 reports the respondents’ approximate position level within their organizations. As reported, the majority of respondents are at or above the supervisory level. The largest segment includes 31 percent of respondents who are at the rank-and-file level (a.k.a. technician).

Twenty-seven percent of respondents are female and 73 percent male.

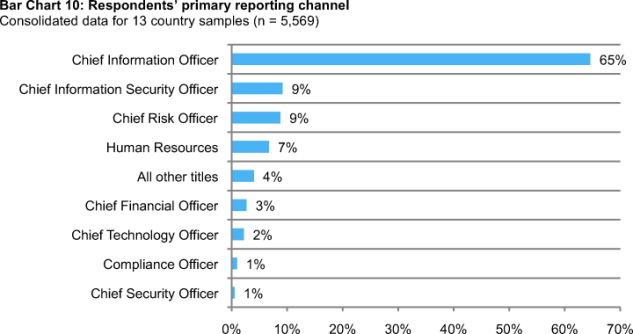

According to Bar Chart 10, 65 percent of respondents report up through the organization’s Chief Information Officer or IT leader with an equivalent title. The second and third most frequently cited reporting channels include the Chief Information Security Officer and the Chief Risk Officer (both at 9 percent).

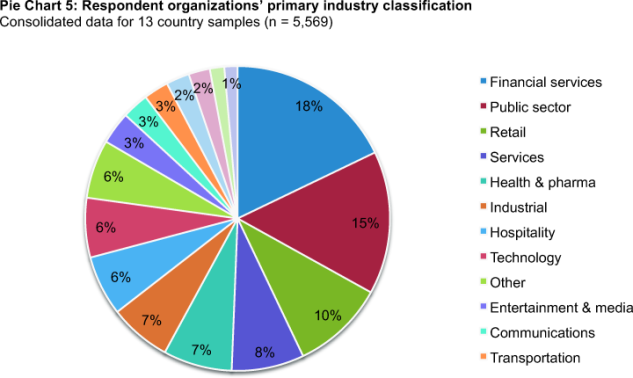

Pie Chart 5 reports the industries represented in the present study, consolidated for all country samples. As can be seen, the largest industry sectors include financial services (18 percent), public sector (15 percent) and retail (10 percent). Financial services include retail banking, insurance, payment/credit cards, brokerage and investment management. Public sector organizations include national, state/provincial and local/municipal entities. In some countries, health care providers are classified as public sector entities.

Limitations

There are inherent limitations to survey research that need to be carefully considered before drawing inferences from findings. The following items are specific limitations that are germane to most web-based surveys.

- Non-response bias: The current findings are based on a sample of survey returns. We sent surveys to a representative sample of IT privileged users located in 13 countries, resulting in a large number of usable returned responses. Despite non-response tests, it is always possible that individuals who did not participate are substantially different in terms of underlying beliefs from those who completed the survey.

- Sampling-frame bias: The accuracy is based on contact information and the degree to which the list is representative of individuals who are IT practitioners who deal with a wide array of issues. We also acknowledge that responses from paper, interviews or telephone might result in a different pattern of findings.

- Self-reported results: The quality of survey research is based on the integrity of confidential responses received from respondents. While certain checks and balances were incorporated into our survey evaluation process, there is always the possibility that certain respondents did not provide responses that reflect their true opinions.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.