Introduction/Region at-a-Glance

Privacy legislation in East, Central and South Asia and the Pacific (Asia) has been extremely active in the past few years, and the level of activity and enforcement does not show any signs of slowing down. Thirteen jurisdictions in Asia now have comprehensive privacy laws: Australia, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Macao, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. New Zealand is the only jurisdiction in the region that has been recognized by the European Commission as providing adequate protection 08 WCRR 18, 1/13/13, 244 Privacy Law Watch, 12/20/12, 11 PVLR 1855, 12/24/12, 13 WDPR 25, 1/25/13.

Notably absent from this list are countries such as China, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia. China is slowly moving toward a privacy regime, taking a piecemeal, sectoral approach. (For a detailed discussion of recent privacy law and network security developments in China, see Paul D. McKenzie & Jing Bu, China Update: Privacy Law and Network Security Developments, 14 Bloomberg BNA Privacy & Sec. L. Rep. 677 (Apr. 20, 2015).) 2015 TERCN 1, 4/20/15, 82 Privacy Law Watch, 4/29/15, 14 PVLR 677, 4/20/15. The governments of Thailand and Indonesia have drafted legislation but the bills have yet to be introduced and/or approved by their respective legislatures. Vietnam also appears to be moving slowly in the development of privacy legislation.

This article examines the commonalities and differences among the privacy laws in the region and discusses current trends and new developments.

Common Elements Found in Asian Laws

Notice:

All of the laws in Asia include some type of notice obligation. That is, every law requires that individuals be told what personal information is collected, why it is collected and with whom it is shared.

Choice:

Every privacy law also includes some kind of choice element. The level or type of consent varies significantly from country to country. For example, South Korea has a much stronger emphasis on affirmative opt-in consent than does New Zealand, but all of the laws include choice as a crucial element in the law.

Security:

Furthermore, all of the laws require organizations that collect, use and disclose personal information to take reasonable precautions to protect that information from loss, misuse, unauthorized access, disclosure, alteration and destruction. Some of the countries—particularly South Korea—have very detailed rules regarding data security that may set the standard for the entire region and also influence the rest of the world.

Access and Correction:

One of the core elements of every privacy law is the right of all individuals to access the information that organizations have collected about them and where possible and appropriate, correct, update or suppress that information. In contrast to their Latin American counterparts, which require organizations to respond to access and correction requests in very short periods of time, many countries in Asia either do not specify specific time frames or provide organizations with a more reasonable time frames, similar to those found in European countries. Notable exceptions include Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, South Korea and Taiwan which have time frames that range from 1-21 days.

Data Integrity:

Organizations that collect personal information must also ensure that their records are accurate, complete and kept up-to-date for the purposes for which the information will be used.

Data Retention:

Generally these laws require organizations to retain the personal information only for the period of time required to achieve the purpose of the processing. Some laws may mandate specific retention periods of time, while others set limits on how long data may be retained by an organization once the purpose of use has been achieved.

Differences in Approaches

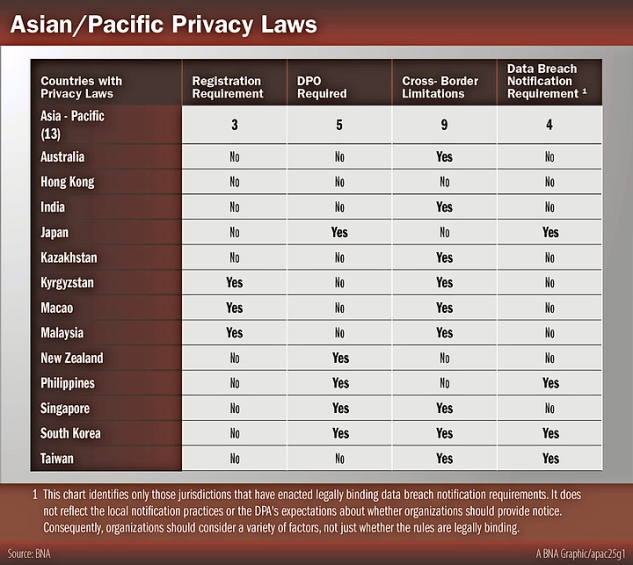

While the core data protection principles and requirements are embodied in all of these laws, specific requirements, particularly with respect to cross-border transfers, registration, data security, data breach notification and the appointment of a data protection officer (DPO), vary widely from each other and from laws in other regions of the world.

For example, two-thirds of the countries in this region restrict cross-border transfers of personal information to countries that do not provide adequate protection. Generally a contract, consent or a contract and consent are required to transfer outside the country. In almost all cases, the data protection authorities (DPAs) have not specified what must be contained in these contracts or rules. Most of the DPAs in the region also have not issued lists of countries that they believe provide adequate protection, and thus companies are left to assume that all countries are deemed to be inadequate and must put in place mechanisms (such as consent or contracts) to satisfy the rules. In addition, unlike their European counterparts, registration is not required in all but three of the jurisdictions in the region.

The differences widen when comparing their respective rules on data breach notification, security and DPO obligations: one-third require notification in the event of a data breach and the appointment of a DPO.

Lastly, three of the countries, Kazakhstan, South Korea and Singapore, rely more heavily on consent to legitimize collection, use and disclosure of personal information.

A careful read of these laws is imperative, therefore. These differences pose challenges to organizations, with respect to the adjustments that may be required to global and/or local privacy compliance practices, as well as privacy staffing requirements. Compliance programs that comply with only European Union and Latin American obligations will run afoul of many of the Asian country obligations.

A country-by-country summary of the obligations in these key areas is provided below. Other noteworthy characteristics are also highlighted and, where applicable, the responsible enforcement authority is identified. In addition, a chart is provided at the end to show at a glance the countries with mandatory cross-border, DPO, data security breach notification and registration obligations.

Trends

Enforcement:

Violations of these laws can result in significant criminal and civil and/or administrative penalties being imposed; however, the enforcement approaches vary widely from one jurisdiction to another. Japan, New Zealand, Australia and Hong Kong encourage businesses and individuals to resolve disputes voluntarily without resorting to the imposition of fines, except in large data breach cases or to signal the regulator’s intent to actively enforce recently enacted rules. In contrast, authorities in South Korea are quick to investigate and impose fines for violations. In Taiwan, the enforcement approach is more varied because enforcement is largely carried out by the competent industry-specific regulators, so the level of enforcement, as well as the interpretations of the compliance obligations under the law, often vary from one regulator to another. In jurisdictions such as Singapore and Malaysia, the regulators are still working with industry to encourage compliance with these new laws, although Singapore recently initiated its first data protection-related enforcement actions, almost two years after the Singapore Law went into effect.

Data Breaches:

The growing number of data breaches in the region has resulted in legislative changes, such as in South Korea, to increase punitive and statutory damages for data breaches, and increased enforcement efforts, particularly against organizations that suffer repeated or massive breaches. For example, in April 2016, the Singapore DPA took enforcement actions against 11 organizations for data protection violations involving data breaches and/or unauthorized disclosures of personal information.

In Australia, the Australian DPA entered into its first enforceable undertaking with Singtel Optus Pty Ltd., Australia’s second-largest telecommunications company, after it suffered three significant data security breaches 61 Privacy Law Watch, 3/31/15, 14 PVLR 621, 4/6/15. After a massive data breach involving three major Korean credit card companies in January 2014, South Korea’s Financial Supervisory Service (FSS) issued a three-month business suspension order against the credit card companies, and several employees of the companies are under investigation by the FSS 07 DER A-2, 1/10/14, 07 Privacy Law Watch, 1/10/14, 13 PVLR 98, 1/13/14. The Financial Services Commission also ordered the companies to cover any financial losses suffered by their customers.

Data breaches have also resulted in increased civil litigation, particularly in Japan and South Korea. For example, in January 2015, a large multi-plaintiff litigation (involving 1,789 plaintiffs) was filed in court in connection with a data breach that affected 48.6 million customers of Benesse Holdings Inc., a Tokyo-based company that operates Shinkenzemi correspondence education courses for schoolchildren 14 PVLR 208, 2/2/15, 21 Privacy Law Watch, 2/2/15. In addition, hundreds of civil actions are now pending for claims arising from the January 2014 credit card breach in South Korea.

Direct Marketing:

There has also been increased enforcement of direct marketing rules in Hong Kong. Since Hong Kong’s new directing marketing provisions of Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (Ordinance) took effect in April 2013, the DPA has, as of January 2016, referred 53 cases for criminal investigation and prosecution. Four of these cases resulted in criminal convictions in 2015.

While the fines imposed in these four cases were relatively low compared to the maximum fines possible under the Ordinance (up to HK$500,000 ($64,343) and 3 years imprisonment), these cases demonstrated the DPA’s determination to vigorously enforce the direct marketing rules.

New Privacy Legislation:

There have been significant changes to the legislative landscape in the region over the past year, particularly in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. In September 2015, Japan enacted legislation to amend the country’s Personal Information Protection Act 173 Privacy Law Watch, 9/8/15, 14 PVLR 1689, 9/14/15. Provisions of the amended law provide for the creation of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC), an independent authority charged with overseeing data protection compliance, as well as other changes such as new rules for processing and handling anonymously processed information and cross boarder transfers of personal data.

South Korea also amended its Personal Information Protection Act in July 2015 and then again in March 2016 58 Privacy Law Watch, 3/25/16, 21 ECLR 467, 3/30/16, 15 PVLR 677, 3/28/16, 131 Privacy Law Watch, 7/9/15, 14 PVLR 1289, 7/13/15, 2016 TLN 20, 4/1/16. Among other things, the 2015 amendments strengthened remedies available to individuals in the event of a data breach by introducing punitive and statutory damages awards and added disgorgement of profits as an available criminal penalty. The March 2016 amendments impose new notice requirements on selected organizations that process large volumes of personal information received from sources other than the individual concerned (e.g., services involving Big Data, Internet of things).

Lastly, in December 2015, Taiwan enacted amendments to its Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), which took effect on March 15, 2016, to address concerns about the rules for processing sensitive personal data and the notice requirements for processing personal data collected prior to the entry into force of the PDPA 16 WDPR 01, 1/21/16, 01 Privacy Law Watch, 1/4/16, 15 PVLR 46, 1/4/16.

Legislation Under Development:

New privacy laws are being debated in Thailand and Indonesia 146 Privacy Law Watch 146, 7/30/15, 14 PVLR 1438, 8/3/15. In January 2015, the Thai Cabinet announced that it had approved “in principle” a draft privacy bill that would impose basic data privacy obligations on organizations such as notice, consent, access, data retention and security 11 Privacy Law Watch, 1/16/15, 14 PVLR 123, 1/19/15. Transfers to countries that do not provide adequate protection would be restricted. The Minister of Digital Economy and Society is the designated agency responsible for enforcement of the law. At present, there are no obligations in the bill that would require registration, the appointment of a DPO or data breach notification.

In October 2015, the Indonesian government issued a draft data protection law, prepared by the Ministry of Communication and Informatics for the 2016 Priority National Legislative Program. Lastly, in December 2015, the Australian Government released an exposure draft of the Privacy Amendment (Notification of Serious Data Breaches) Bill 2015 (the Draft Bill) for public consultation 233 Privacy Law Watch, 12/4/15, 15 WDPR 36, 12/18/15, 14 PVLR 2212, 12/7/15. The government’s proposed breach notification bill follows on the heels of the enactment of a data retention law in March 2015 that requires telecommunications and Internet service providers to collect and retain certain types of communications data for a period of two years. Australia has been discussing the possibility of enacting data breach notification rules since 2008 when the Australian Law Reform Commission first proposed mandatory notification rules; however, concerns about the increased potential for data breaches in light of these new data retention requirements appears to have prompted the government to act.

Under the Draft Bill, which is expected to be introduced into the legislature sometime in 2016, companies will be required to notify the Office of the Australian Information Commission (OAIC) and affected individuals of “serious data breaches.” Failure to comply with the notification obligation set forth in the Bill will be deemed to be an interference with the privacy of an individual for purposes of the Privacy Act, which may result in an investigation and enforcement action by the Privacy Commissioner, and is subject to civil penalties for serious or repeated interferences with privacy.

Country-by-Country Review of Differences

AUSTRALIA

Australia’s Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) (Australian Law) has been amended twice since it was enacted, first in 2000 and most recently in 2012 (231 Privacy Law Watch, 12/3/12)(11 PVLR 1709, 12/3/12)12 WDPR 4, 12/18/12, 231 Privacy Law Watch, 12/3/12. As part of the most recent changes to the law, a single set of privacy principles, referred to as the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs), covering both the public and private sectors was adopted. In addition, a comprehensive credit reporting system that provides for codes of practice under the APPs and a credit reporting code were implemented. The privacy commissioner was also given the authority to develop and register codes that are binding on specified agencies and organizations. The 2012 amendments also clarify the functions and powers of the commissioner and improve the commissioner’s ability to resolve complaints; recognize and encourage the use of external dispute resolution services; conduct investigations; and promote compliance with privacy obligations. Two more rounds of amendments are expected; however, there is no time table for their development and enactment.

In Brief

Like most of the jurisdictions in the region, the Australian Law does not require the appointment of a DPO, registration and data security breach notification; however, the privacy commissioner recommends that organizations appoint a DPO and provide notice in the event of a data security breach. Under the amended law, there are more detailed rules on cross-border transfers, and the application of the law has been expanded to cover all organizations with “Australian links.” Lastly, the exemption for employee records remains intact.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Australian Law is administered by the privacy commissioner in the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (DPA). The DPA has the power to conduct privacy compliance assessments of Australian government agencies and some private sector organizations, accept enforceable undertakings and seek civil penalties in the case of serious or repeated breaches of privacy. In May 2014, the Australian government announced plans to disband the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) for budgetary reasons by Jan. 1, 2015, but the position and responsibilities of the privacy commissioner would remain intact. However, the necessary legislation was not enacted by the end of 2014, so, for the moment, the OAIC remains operational.

Application of the Act

One of the significant changes to the Australian Law is the extension of the APPs to cover overseas handling of personal information by an organization if it has an “Australian link.” An organization has an Australian link if the organization is:

- an Australian citizen;

- a person whose continued presence in Australia is not subject to a limitation as to time imposed by law;

- a partnership formed in Australia or an external territory;

- a body corporate incorporated in Australia or an external territory; or

- an unincorporated association that has its central management and control in Australia or an external territory.

An organization that does not fall within one of the above categories will also have an Australian link where:

- the organization carries on business in Australia or an external territory; and

- the personal information was collected or held by the organization in Australia or an external territory, either before or at the time of the act or practice.

According to the DPA’s guidelines, activities that may indicate that an entity with no physical presence in Australia carries on business in Australia include:

- the entity collects personal information from individuals who are physically in Australia;

- the entity has a website that offers goods or services to countries including Australia;

- the entity includes Australia as one of the countries on the drop-down menu of its website; or

- the entity is the registered proprietor of trademarks in Australia.

Where an entity merely has a website that can be accessed from Australia is generally not sufficient to establish that the website operator is “carrying on a business” in Australia.

Employee Records

The existing exemption for employee records covering “acts or practices in relation to employee records of an individual if the act or practice directly relates to a current or former employment relationship between the employer and the individual” remains intact; the intention is to revisit this issue in subsequent rounds.

Cross-Border Transfers

Before disclosing personal information to a recipient overseas, organizations must take reasonable steps to ensure that the overseas recipient does not breach the APPs in relation to the information received, except where one of the following situations applies:

- the recipient is subject to a law or binding scheme that protects the information in a substantially similar manner, and there are mechanisms available to the individual to enforce that protection;

- the individual is expressly informed that, if he or she consents to the disclosure of the information, the organization is relieved of its obligation to take the required reasonable steps above to ensure that the overseas recipient does not breach the APPs, and, after being so informed, the individual consents to the disclosure;

- the disclosure of the information is required or authorized by or under an Australian law or a court/tribunal order; or

- there is an exception under the law that covers the disclosure of the information by the organization.

The cross-border rules apply to transfers by the organization to its overseas affiliates but not an overseas office.

Data Protection Officer

There is no obligation to appoint a DPO; however, there is a general obligation to implement appropriate practices, procedures and systems to comply with the APPs. The APP guidelines cite the example of designated privacy officers as a possible governance mechanism to ensure compliance with the APPs.

Data Security Breach Notification

There is no obligation under the Australian Law and the APPs to provide notice in the event of a data security breach; however, the DPA has issued voluntary breach notification guidance which recommends that notice be provided to the DPA and affected individuals where the breach creates a real risk of serious harm to individuals. As discussed above, the government has proposed mandatory breach notification legislation which is expected to be introduced into the legislature sometime in 2016.

HONG KONG

Hong Kong was the second jurisdiction in Asia to enact a comprehensive data protection law, in 1995. The Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (Hong Kong Law) protects all personal information of natural persons and applies to both the private and public sectors. The Hong Kong Law was amended in 2012, and one of the most significant changes was to more closely regulate the use and provision of personal information in direct marketing activities 11 PVLR 1117, 7/9/12, 128 Privacy Law Watch, 7/5/12, 12 WDPR 23, 7/26/12. In addition, certain changes to the data protection principles were made, new offenses and penalties were introduced, the authority of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data (DPA) was enhanced and a new scheme whereby the DPA may provide legal assistance to individuals was introduced. The majority of the changes went into effect Oct. 1, 2012; the new direct marketing and the legal assistance provisions took effect April 1, 2013.

In Brief

The Hong Kong Law does not require the appointment of a DPO, data security breach notification or registration; however, the DPA does recommend that organizations appoint a DPO and provide notice in the event of a data security breach. The Hong Kong Law contains a provision that restricts cross-border transfers to countries that do not provide adequate protection; however, the provision is not in force.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data is responsible for enforcement.

Cross-Border Transfers

While the Hong Kong Law contains a provision (Section 33) that limits the transfer of personal information to a place outside Hong Kong that does not provide data protection similar to that under Hong Kong Law, it is not yet in force, and there is no schedule as to when it will come into force. Consequently, transfers both within and outside Hong Kong are governed by general legal restrictions on data collection and data use.

In December 2014, the DPA issued voluntary guidance to help organizations understand their compliance obligations under Section 33. The guidance contains a set of recommended model data transfer clauses for such transfers. The DPA has called upon the government to implement Section 33 and has also developed and submitted to the administration a white list of 50 jurisdictions that, in his view, provide similar protection. If and when Section 33 is implemented, the transfers to jurisdictions on the white list would be exempted from the requirements under Section 33.

Data Protection Officer

There is no statutory requirement to appoint a DPO. However, the DPA recommends it. Appointment of a DPO is a common business practice in Hong Kong.

Data Security Breach Notification

There is no legal obligation on any entities to give notice in the event of a data security breach under the Hong Kong Law; however, the DPA issued voluntary guidance which recommends that organizations “seriously consider” notifying individuals affected by a breach where there is a real risk of harm. Organizations may also choose to notify the privacy commissioner.

Marketing

One of the most significant changes was to more closely regulate the use and provision of personal information in direct marketing activities. Under the new direct marketing rules (seehere for guidance on the rules), an organization can only use or transfer personal information for direct marketing purposes if that organization has provided the required information (notice) and consent mechanism to the individual concerned and has obtained his or her consent. “Consent” in the direct marketing context includes an indication of no objection to the use (or provision); however, written consent is required prior to providing personal information to others for their direct marketing purposes. Failure to comply with these requirements is a criminal offense, punishable by fines of HK$500,000 ($64,343) and three years’ imprisonment. In cases involving transfer of personal data for gain, a fine of HK$1 million ($128,686) and five years’ imprisonment are possible.

INDIA

In 2011, India issued final regulations implementing parts of the Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008 dealing with protection of personal information 88 Privacy Law Watch, 5/6/11, 88 International Business & Finance Daily, 5/6/11, 88 DER A-2, 5/6/11, 2011 IDSN, 5/13/11, 10 PVLR 687, 5/9/11. The Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011 (Indian Privacy Rules) prescribe how personal information may be collected and used by virtually all organizations in India, including personal information collected from individuals located outside of India.

In Brief.

The Indian Privacy Rules do not require the appointment of a DPO, data security breach notification or registration. There are limitations on cross-border transfers, but they apply only to sensitive personal information. Furthermore, as explained below, outsourcing providers are subject to a narrower set of obligations, the consent obligations only apply to sensitive information and sensitive information is very broadly defined.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Ministry of Communications & Information Technology is responsible for enforcement of the Indian Privacy Rules.

Application of the Rules

The Indian Privacy Rules raised significant issues and caused concern among organizations that outsource business functions to Indian service providers. As drafted, the Indian Privacy Rules apply to all organizations that collect and use personal information of natural persons in India, regardless of where the individuals reside or what role the company that is collecting the information plays in the process of handling the information. In particular, the provisions apply to a “body corporate,” which is defined as “any company and includes a firm, sole proprietorship or other association of individuals engaged in commercial or professional activities,” as well as, in many instances, “any person on its behalf.” As a result, industry both within and outside India expressed concern that the Indian Privacy Rules would decimate the outsourcing industry.

In response to these concerns, on Aug. 24, 2011, the Indian Ministry of Communication & Technology issued a clarification of the Indian Privacy Rules (Clarification), stating that the Indian Privacy Rules apply only to organizations in India 166 International Business & Finance Daily, 8/26/11, 10 PVLR 1240, 9/5/11, 166 Privacy Law Watch, 8/26/11, 11 WDPR 24, 9/23/11. Therefore, if an organization in India receives information as a result of a direct contractual relationship with an individual, all of the obligations under the Indian Privacy Rules continue to apply. However, if an organization in India receives information as a result of a contractual obligation with a legal entity (either inside or outside India), e.g., is acting as a service provider, the substantive obligations of notice, choice, data retention, purpose limitation, access and correction do not apply, but the security obligations and the obligations relating to the transfer of information do apply.

Consent

The consent rules apply only to sensitive information.

Sensitive Information

Sensitive information is very broadly defined and includes information that is not generally regarded as sensitive in other jurisdictions. In particular, it is defined as information relating to: (i) password; (ii) financial information such as bank account or credit card or debit card or other payment instrument details; (iii) physical, physiological and mental health condition; (iv) sexual orientation; (v) medical records and history; (vi) Biometric information; (vii) any detail relating to the above clauses as provided to body corporate for providing service; and (viii) any of the information received under above clauses by body corporate for processing, stored or processed under lawful contract or otherwise; provided that, any information that is freely available or accessible in public domain or furnished under the Right to Information Act, 2005 or any other law for the time being in force shall not be regarded as sensitive personal data or information for the purposes of these rules.

Cross-Border Transfers

An organization may transfer sensitive personal information to any organization or person in India or to another country that ensures the same level of data protection; however, the government has not issued a list of countries that, in its view, provide such protection. The transfer may only be allowed if it is necessary for the performance of the contract between the organization (or its agent) and the individual or where the individual has consented to the transfer.

JAPAN

In September 2015, Japan enacted legislation to amend the country’s 2005 Personal Information Protection Act which regulates the handling of personal information of natural persons by private sector organizations (Japanese Law). Provisions of the amended law that provide for the creation of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC), an independent authority charged with overseeing data protection compliance, came into force on Jan. 1, 2016; the remaining provisions will take effect in August 2017. The creation of the PIPC represents a significant change in the approach to enforcement which, until now, has been the responsibility of national administrative agencies and local governments. As part of their supervision responsibilities, these agencies have issued to-date 39 data protection guidelines covering 27 different areas or sectors.

In Brief

After the amendments take effect in September 2017, the Japanese Law will impose restrictions on cross-border transfers; however, currently there are no such restrictions. There are special notice rules for sharing with third parties and, under some of the ministry guidelines, there are requirements to appoint a DPO and provide notice in the event of a data security breach. There are no registration requirements, however.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

Under the 2015 amendments, the Personal Information Protection Commission (DPA), an independent government authority, has been established to unify authority relating to data protection under a single governmental agency. Up until now, the data protection rules have been enforced and interpreted by the ministries responsible for enforcement in their individual sectors: the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI); the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) (formerly the Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunication); the Ministry of Finance (FSA); the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW); and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) (a complete list of the guidelines and responsible ministries is available here.

Each ministry issued guidelines detailing specific obligations and recommendations. As a result, businesses operating in Japan have to carefully examine the guidelines issued by the competent ministries under whose jurisdiction they operate. A business may be subject to multiple guidelines depending on the scope of its business operations, and the provisions of such guidelines may not be the same. In fact, they may actually conflict. When the remaining provisions of the law come into force on Sept. 9, 2017, supervision of compliance with the law will transfer from the competent Ministers to the DPA.

Cross-Border Transfers

Prior to the 2015 amendments, the law did not impose limitations on cross-border transfers; however, the rules for disclosures to third parties did apply. These current rules require that personal information not be provided to third parties without prior consent of the individual unless an opt-out notice of third-party sharing has been provided prior to the personal information being collected. Once the amended rules take effect, individuals’ consents will be required to transfer personal information to foreign third parties unless the DPA recognizes that the country has the same level of protection as the Japan Law or a foreign third party has a system that meets the DPA’s specified standard.

Data Protection Officer

There is no requirement for a DPO under the Japanese Law; however, under some of the ministry guidelines, a DPO is required or recommended. In particular, a DPO is required in the financial and credit sectors and recommended in other sectors.

Data Security

Organizations must adopt measures necessary and appropriate for preventing the divulgence, loss or damage of personal information and otherwise control the security of that information. In addition, some of the guidelines impose more extensive security requirements, including encryption and service provider supervision. When the amendments take effect, organizations that create anonymized information will be required to sanitize the personal information in accordance with standards to be issued by the DPA.

Data Security Breach Notification

Data security breach notification is not explicitly addressed in the Japanese Law but is addressed in the ministry guidelines. Citing the Japanese Law’s security control measures as the basis for their notification obligations, some of the ministry guidelines require or expect notification whenever there is a loss of personal information.

Joint Use Notice

If an organization intends to jointly use personal information with third parties (including corporate affiliates), it must provide information on the scope of joint users, items of personal information to be jointly used, purpose of joint use and the name of the individual or entity primarily responsible for the management of the data. The information must be provided through a notice to the individual or by placing the individual in circumstances whereby he or she can easily find out. Any change in purposes of joint use and/or the name of the individual or entity primarily responsible for the management of the data must also be notified to the individuals or publicly announced.

KAZAKHSTAN

The Law on Personal Data and Protection (Kazak Law), which went into effect in November 2013, protects all personal information of natural persons and applies to both the private and public sectors. The law was amended in November 2015 to impose new data localization requirements, effective January 2016.

In Brief

The Kazak Law restricts cross-border transfers to countries that do not protect personal information. It also imposes data localization requirements and exceedingly short timeframes for responding to access and correction requests. However, there are no data breach notification, special security, DPO, or registration requirements.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

There is no independent data protection authority responsible for enforcement of the Kazak Law. In practice, the General Prosecutor’s Office and its territorial bodies are authorized to investigate and initiate administrative cases involving data protection law violations; the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Ministry of Finance are responsible for investigating and initiating criminal cases involving data protection law violations.

Access and Correction

Access requests must be acted upon within three working days; correction requests must be acted upon within one day.

Cross-Border Transfers

Personal information may be transferred without restriction to a country that protects personal information. However, to transfer personal information to a country that does not provide such protection, consent or another one of the very limited exceptions must apply.

Data Localization

Effective Jan. 1, 2016, companies established in Kazakhstan as well as representative offices and branches of foreign companies that own or operate databases containing personal information must store personal information in Kazakhstan. It is unclear, however, if this storage requirement applies to foreign companies without any legal presence in Kazakhstan, whose operations are aimed at Kazakhstan and whose websites are accessible in the territory of Kazakhstan (e.g. Internet companies).

KYRGYZSTAN

The Law on Personal Data (Kyrgyz Law) (available in Russian here), which went into effect in April 2008, protects all personal information of natural persons and applies to both the private and public sectors.

In Brief

The Kyrgyz Law restricts cross border transfers, requires database registration (not yet in force), and imposes exceedingly short timeframes for responding to access and correction requests. In addition, similar to laws in the EU, the Kyrgyz Law requires organizations to have a legal basis for processing personal information such as consent, legitimate interests, vital interests, or legal requirements. However, the Kyrgyz Law does not impose data breach notification, special security, or DPO requirements.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Kyrgyz Law requires the government to designate a specific state body to regulate the collection and use of personal information, handle registrations, maintain records of personal data files and holders of such files, and make international agreements on the cross-border transfer of personal information. The State Registration Service, the public authority responsible for, among other things, implementing the country’s informatization policy and supervising business activities and programs in this sector, has some but not all of the DPA functions set forth in the law. In particular, the State Registration Service has not been given authority over the registration process for personal data holders.

Access and Correction Requests

Access and correction requests must be fulfilled within seven days.

Cross-Border Transfers

Personal information may not be transferred to countries that do not provide an adequate level of protection unless one of the limited exceptions applies such as consent or vital interests.

Legal Basis for Collection and Use

Similar to EU law, the Kyrgyz Law requires organizations to have a legal basis for processing personal information such as: the individual has consented to the processing (consent); the processing is necessary to pursue a legitimate interest of the organization (legitimate interests), the processing is necessary to protect the vital interests of the individual (vital interests) or the processing is necessary to comply with a legal requirement (legal requirement).

Registration

Companies must register with their personal data files with the DPA; however, as of April 2016, the government has yet to designate a state authority responsible for registration.

MACAO

The Personal Data Protection Act (Macao Law), which took effect in 2006, was the first jurisdiction in Asia to adopt an EU-style data protection law. Virtually all of the provisions (notice, consent, collection and use, data security, data integrity, data retention, access and correction, cross-border limitations and registration) closely follow the requirements found in EU member state laws. The Macao Law applies to both the public and private sector processing of personal information of natural persons. Macao was the first jurisdiction in the region to require registration and impose EU-style cross-border restrictions.

In Brief

The Macao Law imposes restrictions on cross-border transfers that mirror EU member state cross-border border restrictions and requires registration of databases. It does not require the appointment of a DPO or data security breach notification.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Office for Personal Data Protection (DPA) is responsible for enforcement.

Registration

Registration is required unless an exemption applies.

MALAYSIA

The Personal Data Protection Act (Malaysian Law) was enacted in 2010 but did not come into effect until November 2013 225 DER A-4, 11/21/13, 225 Privacy Law Watch, 11/21/13, 12 PVLR 2002, 11/25/13; organizations were given three months (until Feb. 15, 2014) to comply. The Malaysian Law protects all personal information of natural persons processed in respect to “commercial transactions” (explained below) that are (i) processed in Malaysia and (ii) processed outside Malaysia where the data are intended to be further processed in Malaysia. The Malaysian Law does not apply, however, to personal information processed by federal and state governments.

In Brief

The Malaysian Law restricts cross-border transfers and requires registration. It does not require the appointment of a DPO or data security breach notification.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Department of Personal Data Protection (DPA), located within the Ministry of Communication and Multimedia, is responsible for regulating and overseeing compliance with the Malaysian Law.

Application of the Law

A “commercial transaction” is defined as “any transaction of a commercial nature, whether contractual or not, which includes any matters relating to the supply or exchange of goods or services, agency, investments, financing, banking and insurance, but does not include a Credit Reporting Business carried out by a Credit Reporting Agency under the Credit Reporting Agencies Act 2009.” Given this definition, there has been much speculation about whether this law would apply to the processing of human resources data. While no official guidance has been issued, all indications are that the Malaysian Law does apply to human resources data.

Cross-Border Transfers

Organizations may only transfer personal information to countries outside Malaysia that have been approved by the minister of communication and multimedia unless an exception applies. The exceptions largely mirror those found in many European laws, such as:

- the individual has consented to the transfer;

- the transfer is necessary to perform a contract with or at the request of an individual;

- the transfer is for the purpose of any legal proceedings or for the purpose of obtaining legal advice or for establishing, exercising or defending legal rights;

- the transfer is necessary in order to protect the vital interests of the individual; or

- the organization has taken all reasonable precautions and exercised all due diligence to ensure that the personal information will not be processed in any manner which, if the data were processed in Malaysia, would be a contravention of the act.

As of April 2016, no countries have been approved. Approved countries will be published by the minister in the official Gazette.

Registration

Data users (mainly licensed organizations) from the following sectors are required to register: communications, banking and financial institutions, insurance, health, tourism and hospitalities, transportation, education, direct selling, services (such as legal, audit, accountancy, engineering or architecture and retail or wholesale dealing as defined under the Control Supplies Act 1961), private employment agencies, real estate and utilities.

NEW ZEALAND

New Zealand was the first country in the region to enact a data protection law. The Privacy Act 1993 (New Zealand Law), which regulates the processing of all personal information of natural persons by both the public and private sectors, is also the first and only law in Asia to be recognized by the EU as providing an adequate level of protection for personal data transferred from the EU/European Economic Area . This adequacy determination was issued after New Zealand amended its law in 2010 to establish a mechanism for controlling the transfer of personal information outside of New Zealand in cases where the information has been routed through New Zealand to circumvent the privacy laws of the country from where the information originated 173 Privacy Law Watch, 9/9/10, 10 WDPR 15, 9/24/10, 9 PVLR 1287, 9/13/10.

In Brief

The New Zealand Law requires the appointment of a DPO but does not restrict cross-border transfers or require registration. There are no mandatory requirements to provide notice in the event of a data security breach; however, such notice is recommended by the DPA.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner (DPA) regulates and administers the New Zealand Law.

Data Protection Officer

A DPO must be appointed regardless of the size of the agency. One DPO per agency is required.

Data Security Breach Notification

There are no mandatory notification obligations; however, the DPA has issued voluntary guidelines that recommend notice be provided to individuals and/or the DPA in the event of a security breach that presents a risk of harm to the individuals whose personal information is involved in the breach. Necessity to provide notice should be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

THE PHILIPPINES

Philippine President Benigno Aquino III signed the Data Privacy Act of 2012 (Philippine Law) into law Aug. 15, 2012 164 International Business & Finance Daily, 8/24/12, 17 ECLR 1568, 8/29/12, 164 Privacy Law Watch, 8/24/12, 11 PVLR 1357, 9/3/12, 12 WDPR 18, 9/21/12. The law entered into force Sept. 8, 2012. Organizations have one year from when the implementing rules and regulations become effective (or another period determined by the DPA) to come into compliance with the law. Implementing regulations have yet to be issued; however, with the President’s appointment of the three members of the National Privacy Commission in March 2016, the expectation is that the implementing rules and regulations will be issued soon.

In Brief

The Philippine Law imposes the same rules for both domestic and international (cross-border) transfers and requires the appointment of a DPO and data security breach notification. It does not require registration. In addition, the Philippine Law contains an exemption for outsourcing providers.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Philippine Law establishes the National Privacy Commission (the Commission) as a DPA located within the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT). The Commission, whose leadership was appointed by the President in March 2016, will be responsible for administering, implementing and monitoring compliance with the Philippine Act, as well as investigating and settling complaints. However, unlike many other data protection authorities, it will not have the power to directly impose penalties; it can only recommend prosecution and penalties to the Department of Justice.

Application of the Law

The Philippine Law applies to the processing of all personal information of individuals by public and private sector organizations with some important exceptions. For example, personal information that is collected from residents of foreign jurisdictions in accordance with the laws (e.g., data privacy laws) of those jurisdictions and that is being processed in the Philippines is excluded. This exception is relevant for companies that outsource their processing activities to the Philippines. As a result, outsourcing providers in the Philippines will not need to comply with the Philippine Law’s requirements for information collected as part of their outsourcing operations relating to personal information received from outside the Philippines.

In addition, the Philippine Law also applies to organizations and service providers that are not established in the Philippines but that use equipment located in the Philippines or maintain an office, branch or agency in the Philippines. It also applies to processing outside the Philippines if the processing relates to personal information about a Philippine citizen or a resident and the entity has links to the Philippines. This last provision seeking to extend the obligations of the law based on the citizenship of the individuals is very unusual in data protection laws.

Cross-Border Transfers/Transfers to Third Parties

Organizations are responsible for personal information under their control or custody, including information that has been transferred to a third party for processing, whether domestically or internationally, subject to cross-border arrangement and cooperation. Organizations are accountable for complying with the requirements of the Philippine Law and must use contractual or other reasonable means to provide a comparable level of protection while the information is being processed by a third party. This approach to domestic and international transfers is similar to the approaches found in Canadian and Japanese laws that are based on the concept of accountability.

Data Protection Officer

While registration is not required for private sector organizations, organizations must designate one or more individuals to be accountable for the organization’s compliance with the Philippine Law.

Data Security Breach Notification

Organizations must promptly notify the Commission and affected individuals when sensitive personal information or other information that might lead to identity fraud has been, or is reasonably believed to have been, acquired by an unauthorized person, and the Commission or the organization believes that such unauthorized acquisition is likely to give rise to a real risk of serious harm to any affected individual. Notification must describe the nature of the breach, the sensitive personal information believed to be involved and measures taken to address the breach. The Commission may exempt an organization from the requirement to provide notice to individuals if he or she decides that notification is not in the interest of the public or the affected individual.

SINGAPORE

Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (Singapore Law) came into force in January 2013 200 Privacy Law Watch, 10/17/12, 11 PVLR 1562, 10/22/12, 12 DDEE 438, 10/25/12, 07 WCRR 11, 11/17/12. The Singapore Law governs the collection, use and disclosure of personal information by private sector organizations. It also prohibits the sending of certain marketing messages to Singapore telephone numbers, including mobile, fixed-line, residential and business numbers registered with the Do Not Call (DNC) Registry. The Singapore Law was implemented in phases, with the DNC Registry provisions coming into force in January 2014 and the data protection rules coming into force in July 2014 2014 TLN 24, 7/1/14, 09 WCRR 20, 6/15/14, 101 Privacy Law Watch, 5/27/14, 13 PVLR 978, 6/2/14.

The following summarizes the special characteristics of data protection provisions only. It does not address the DNC Registry provisions contained in the Singapore Law.

In Brief

The Singapore Law restricts cross-border transfers and requires the appointment of a DPO. Data security breach notification and registration are not required. The Singapore Law provides special exemptions for outsourcing providers and the collection, use and disclosure of business contact information.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Personal Data Protection Commission is responsible for enforcement of the Singapore Law.

Application of the Law

The Singapore Law applies to all private sector organizations incorporated or having a physical presence in Singapore; however, service providers that process on behalf of other organizations are exempted from all but the security and data retention provisions. All personal information of natural persons is protected with some important exceptions. For example, business contact information—defined as an individual’s name, position name or title, business telephone number, address, e-mail or fax number and other similar information—is exempted from the provisions pertaining to the collection, use and disclosure of personal information.

Cross-Border Transfers

Transferring organizations are required to take appropriate steps to determine whether, and ensure that, the recipient outside Singapore is bound by legally enforceable obligations to provide the transferred information with a comparable standard of protection. To satisfy these requirements, consent, a transfer contract, binding corporate rules or another exception under the Singapore Law must apply.

Data Breach Notification

There is no express obligation under the Singapore Law on any entities to give notice in the event of a data security breach. However, in May 2015, the DPA issued a Guide to Managing Data Breaches which recommends that individuals whose personal information has been compromised, be notified immediately if a data breach involves sensitive Personal Data. The DPA should be notified of any data breaches that might cause public concern or where there is a risk of harm to a group of affected individuals.

Data Protection Officer

Organizations must designate one or more data protection officer(s) responsible for ensuring the organization’s compliance with the Singapore Law.

SOUTH KOREA

The Data Protection Act (PIPA or Korean Law), which took effect in September 2011 and was subsequently amended in 2015, regulates public and private sector processing of personal information of natural persons. PIPA serves as the umbrella privacy law in South Korea; however, there are various sector-specific laws, such as the Act on the Promotion of IT Network Use and Information Protection (the Network Act), the Use and Protection of Credit Information Act, the Electronic Financial Transactions Act and the Use and Protection of Location Information Act, that also regulate privacy and cybersecurity. The Network Act, enacted before PIPA, regulates the processing of personal information in the context of services provided by telecommunications service providers and commercial website operators. While the privacy-related provisions are similar to PIPA, the Network Act regulates issues not covered by PIPA, such as spam.

In Brief

The Korean Law restricts cross-border transfers and requires the appointment of a DPO and data security breach notification. It also imposes extensive obligations in such areas as notice, consent and data security. Registration is not required, however.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Ministry of the Interior (MOI), formerly the Ministry of Government Administration and Home Affairs, is the authority responsible for enforcing the Korean Law.

Notice and Consent

Prior notice and express consent are required to collect, use and transfer personal information. The notice must separately detail the collection and use of personal information, third-party disclosures (including any cross-border disclosures), processing for promotional or marketing purposes, processing of sensitive information or particular identification data (such as resident registration number and passport number), disclosures to third-party outsourcing service providers and transfers in connection with a merger or acquisition. The individual must consent separately to each item. The uses that do not require consent must be distinguished from those that do require consent.

Cross-Border Transfers

If an organization intends to provide personal information to a third party across the national border, it must give notice and obtain specific consent to authorize the cross-border transfer.

Data Protection Officer

Organizations must appoint a DPO with specified responsibilities.

Data Security

The Korean Law and subsequent guidance issued by the regulatory authorities also impose significant data security obligations. These data security requirements are some of the most detailed in the world. For example, organizations are required to encrypt particular identification data, passwords and biometric data when such data are in transit or at rest. If personal information is no longer necessary after the retention period has expired or when the purposes of the processing have been accomplished, the organization must, without delay, destroy the personal information unless any other law or regulation requires otherwise. In addition, under the recent amendments, organizations that process “Particular Identification Information” (i.e., resident registration numbers, passport numbers, driver’s license numbers, and alien registration numbers) will be subject to regular inspections by the Minister of the Interior (or a designated specialized agency) to determine whether they have implemented measures necessary to ensure the security of the Particular Identification Information.

Data Security Breach Notification

When becoming aware of a leak of personal information, organizations must, without delay, notify the relevant individuals, prepare measures to minimize possible damages and, when the volume of affected data meets or exceeds a threshold set by executive order (i.e., in the case of a leak involving 10,000 or more individuals), notify the regulatory authorities concerned or certain designated specialist institutions. Individuals who suffer damages resulting from a data breach caused by an organization’s willful misconduct or gross negligence may be entitled to punitive damages of up to three times the actual damages. In addition, individuals whose personal information has been lost, stolen, or leaked due to a data breach caused by negligence or willful misconduct may request statutory damages of up to 3 million won ($2,520).

TAIWAN

Taiwan’s Personal Data Protection Act (Taiwanese Law) entered into effect in October 2012 12 WDPR 25, 9/21/12, 11 PVLR 1322, 9/3/12, 169 Privacy Law Watch, 8/31/12. The Taiwanese Law, which replaces the 1995 Computer Processed Personal Data Protection Act that regulated computerized personal information in specific sectors such as the financial, telecommunications and insurance sectors, now provides protection to personal information of natural persons across all public and private entities and across all sectors. In December 2015, the Taiwanese Law was amended to address concerns about the rules for processing sensitive personal data and the notice requirements for processing personal data collected prior to the entry into force of the PDPA. Those amendments went into effect on March 15, 2016.

In Brief

The Taiwanese Law requires data security breach notification but does not restrict cross-border transfers or require the appointment of a DPO or registration of databases.

Special Characteristics

Data Protection Authority

The Ministry of Justice has overall responsibility for the Taiwanese Law; however, the individual government agencies that regulate specific industry sectors are authorized to regulate compliance by organizations under their regulatory jurisdiction.

Cross-Border Transfers

There are no restrictions imposed on cross-border transfers; however, the central competent authority for a specific industry may restrict cross-border transfers in certain circumstances, such as if the recipient country does not yet have proper laws and regulations to protect personal information so that the rights and interests of the individual may be damaged or personal information is indirectly transferred to a third country to evade the Taiwanese Law.

Data Security Breach Notification

Individuals must be notified when their personal information has been stolen, divulged or altered without authorization or infringed upon in any way.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.