The America Invents Act

The USPTO is the third-busiest forum for determinations of patent validity in the United States. Yet only about 5% of the more than 1,000 AIA petitions to date have involved biotechnology or pharmaceutical patents. Pharmaceutical companies have not generally taken advantage of new litigation strategies available under the AIA. The companies that do so will be better positioned to gain or retain market share.

These new proceedings provide generic drug companies (“generics”) with a second line of attack against brand drug companies. Brand drug companies whose patents survived ANDA district court litigation often times believed that they were “home free” for the remaining term of the patent, even though others could attack the patent in other litigation. Assuming that surviving ANDA litigation provided much comfort to brand drug companies, this is no longer the case. Pharmaceutical patents are now subject to repeated challenges to the same patent by any party willing to pay the relatively low USPTO filing fee for a post-grant procedure. These new proceedings should be considered an integral part of the intellectual property litigation strategy of all pharmaceutical companies. Generics should understand the potential advantages these new proceedings present for entering the market earlier and at lower cost, and brand companies should be prepared to defend their patents when a generic files one of these new USPTO proceedings. Brand companies may also use these new proceedings to their strategic advantage, for example by invalidating a patent held by their competition or as an alternative to obtaining a license to a blocking patent, at much lower cost and more quickly before the USPTO.

Traditional ANDA Litigation

A generic desiring to enter the market before the expiration of the brand drug patent can file a paragraph IV certification asserting that an Orange Book listed patent is invalid or will not be infringed by the generic’s product.

So What’s Changed?

After the passage and implementation of the AIA, Orange Book listed patents are subject to two lines of attack if the paragraph IV certification is based, at least in part, on invalidity. The new post-grant procedures to challenge the validity of patents are much less expensive and easier for the challenger to win as compared with district court ANDA litigation. It gives the generic a second line of attack against the brand name drug company’s patents. By instituting a post-grant procedure, generics can also increase the pressure on the brand drug company to settle the ANDA litigation and post-grant procedure before the claims of the brand patent are potentially invalidated by the district court or the USPTO. One issue, discussed below, is whether the first to file generic will forego the 180-day exclusivity period if the USPTO invalidates the patent before the district court action is complete. This creates some risk for the generic and must be taken into account in developing a litigation strategy.

The New USPTO Proceedings

There are two new proceedings at the USPTO that can be used to invalidate pharmaceutical patents: Inter Partes Review (“IPR”) and Post Grant Review (“PGR”). PGR and IPR proceedings possess tremendous advantages over district court ANDA litigation. Both PGRs and IPRs reduce litigation costs and quickly resolve potential infringement liability. These advantages most obviously benefit generics, but brand companies may utilize post-grant procedures to their advantage in certain situations. If a brand is not concerned about tipping its hand for future plans, it may want to eliminate third party patents that its new product could potentially infringe. A brand drug company may also choose to invalidate a third party patent in a post-grant procedure as an alternative to licensing the patent.

An IPR petition may be filed by anyone other than the patent owner who desires to challenge the patentability of a claim of a patent.

One of the risks that a company must consider before filing an IPR or a PGR is the application of the estoppel provisions. Simply stated, estoppel means that the party that brought the IPR or PGR cannot raise the same issue again regarding the same patent either in court or before the USPTO. The reason for the estoppel provisions is that the patent owner should not be subject to multiple challenges on the same patent from the same party. The petitioner is estopped from bringing again before a district court, the International Trade Commission (ITC) or the USPTO any grounds actually raised or that reasonably could have been raised in the IPR or PGR. §§ 315(e), 325(e). Estoppel applies only to claims and grounds actually instituted by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), provided that they were raised in the petition. See Changes to Implement Inter Partes Review Proceedings, Post-Grant Review Proceedings, and Transitional Program for Covered Business Method Patents, 77 Federal Register 48680, 48703 (“[O]nly those claims upon which review is instituted are subject to estoppel.”). Consequently, a thorough prior art search is a prerequisite to the filing of an IPR or a PGR. In addition, it is not wise to file a PGR only on anticipation or obviousness grounds (§§102, 103) since the estoppel provisions currently are much broader for a PGR because more grounds potentially can be raised.

Relative to district court litigation, it is easier to invalidate a patent in an IPR or PGR because claim terms are given their broadest reasonable interpretation by the PTAB.

Microso

ft Corp. v. i4i Ltd. Partnership,

Challenging a patent before the USPTO may have the additional benefit that the judges have scientific backgrounds and are knowledgeable about patent law concepts. The judges are more likely to understand and appreciate chemical compounds and therapeutic methods over a jury or a district court judge. This is especially true when seeking to invalidate a patent on obviousness using a combination of prior art references, particularly those that are difficult for the trier of fact in a district court to appreciate. Conversely, there may be situations where the scientific sophistication of the USPTO judges benefits the patentee.

Discovery is very limited before the PTAB, making the proceedings much less costly. Automatic or routine discovery is limited to (1) the production of any exhibit cited in a paper or testimony; (2) the cross-examination of the other side’s declarants; and (3) non-privileged relevant information that is inconsistent with a position advanced during the proceeding.

Below is a chart that illustrates the major differences between litigating before the USPTO, district court and the International Trade Commission:

Another unique feature of the USPTO trial proceedings is that the USPTO is not required to resolve every case. A preliminary decision whether to institute a trial is obtained within six months of filing the petition and the proceedings are generally completed within 18 months of filing. Although the law gives the Director of the USPTO an additional six months to enter a final written decision where warranted, this additional six months has not been used to date. §§316(a)(11), 326(a)(11). As a result, these proceedings are resolved quickly.

In the preliminary decision of an IPR, the PTAB institutes the IPR if there is a “reasonable likelihood” that at least one of the claims of the patent is unpatentable. §314(a). The standard is slightly higher for the institution of a PGR; the PTAB must find that it is “more likely than not” that at least one of the claims is unpatentable. This preliminary determination within six months of filing the petition incentivizes the parties to reach an early settlement. For all of these reasons, filing an IPR before the PTAB has become the preferred route to invalidate a patent. This has been borne out in the number of filings, with the PTAB having the third-largest patent docket in the country after the Eastern District of Texas and the District of Delaware. Because PGR applies only to first-to-file patents and must be filed after the grant of the patent, there are no PGR filings that have been instituted (one was filed but not instituted).

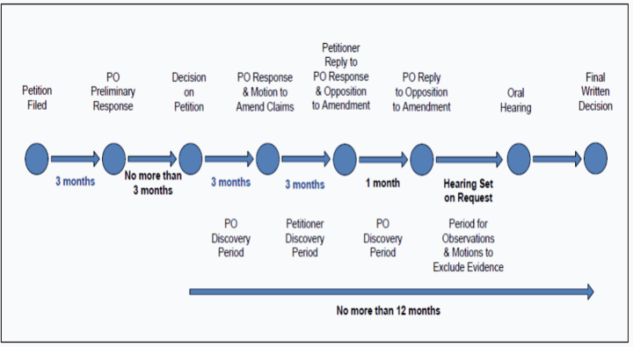

For ease of handling the three types of proceedings, the USPTO issued umbrella procedures that apply to IPRs and PGRs alike. See below for a timeline of the new proceedings (PO refers to patent owner in the image).

The Strategic Implications

The new USPTO post-grant proceedings provide new strategic considerations for both brand companies and generics. Some of those strategic considerations are presented below. Keep in mind that the best strategy will depend upon the particular circumstances. This is not a situation where one size fits all.

- More Pressure to Settle ANDA Litigation

As part of their litigation strategy, generics should now consider filing an IPR before the USPTO to challenge patents on brand drugs. Even if the generic is engaged in ANDA litigation in district court, filing an IPR may put additional pressure on the brand to settle. One significant concern for generics is whether they would forego the 180 days of exclusivity, if the USPTO invalidates the patent before a district court does the same. There is some support that it might. See

A generic may also file the paragraph IV certification based on non-infringement, and then file an IPR based on invalidity as a separate challenge. This may make it attractive in some cases for the brand drug manufacturer to ask the district court to stay the ANDA litigation pending the outcome of the IPR. This is an unusual tactic outside of the ANDA context, where the plaintiff in an infringement action would rarely seek a stay of district court litigation. In an ANDA litigation, it often makes tactical sense for the brand drug manufacturer to seek a stay because the patent may not be invalidated by the USPTO and the brand could continue to market the drug under its patent monopoly until the ANDA litigation is resolved. In addition, this may increase the pressure on the generic to settle due to the threat that it could lose its 180-day exclusivity, especially if there are other generics poised to enter the market. Making this scenario even more complicated is the 30-month stay of ANDA approval by the FDA after the notice of the brand to invoke litigation. The brand manufacturer will surely be incentivized to seek an extension of the 30 month stay should the litigation run long.

If an IPR is filed in parallel with district court ANDA litigation, then there is a race to judgment to determine which action will control the validity of the patent between the two parties. See Fresenius USA, Inc. v. Baxter Int’

l, Inc.,

Filing an IPR may goad a brand company into a settlement because substantially all of IPR decisions to date have invalidated the patents at issue. A brand company may seek a settlement to preserve its patents so that they may be enforced against other adversaries. Brand companies also have an incentive to settle an IPR early in the proceeding because the USPTO has proceeded with IPRs where the settlement occurred in the advanced stages of the IPR. Thus, the brand is at risk of giving up rights in the settlement and having its patent invalidated if it waits too long to settle. There are many strategic considerations to be considered here depending on the particular circumstances involved.

- Brand Manufacturers Should Consider Filing a PGR

Brand companies engaging in research and development should monitor the patent publications of their competitors and consider filing a PGR if they are developing a pharmaceutical that potentially infringes the competitor’s patent. In this way, where the brand company is not concerned with revealing its plans, the brand manufacturer can use the USPTO post-grant proceeding offensively to quickly resolve any potential infringement liability at a much lower cost than waiting for district court litigation to ensue.

Brand companies could also consider encouraging a third party to invalidate a patent that may impede its freedom to operate. This option is particularly attractive where a license with acceptable terms is difficult to obtain. One potential issue with this approach is that the third-party petitioner cannot be controlled by the brand company such that they are in privity or the brand company is the real party in interest.

Further, in recent years, the line between brand companies and generics has blurred, with brand companies becoming involved with marketing generic drugs and generics engaging in innovation. Thus, a brand company whose patents are under attack from a generic may include a post-grant procedure counterattack against the generic’s patents as part of its strategy to force a settlement.

- Second Generics Have Nothing to Lose By Filing an IPR

Second to file (or later) generics should consider filing an IPR because it could potentially allow them to enter the market sooner, taking away the first to file generic’s 180 days of exclusivity. In addition, second generics may have little to lose by filing an IPR. In contrast to the first to file generic, a later filer may try to institute IPRs against all of the Orange Book listed patents. A later filer who invalidates all the patents in an IPR prior to the conclusion of the district court ANDA litigation will deprive the first to file generic from obtaining the market exclusivity period.

- File IPR Before Research and Development

If generics are engaging in research and development to determine bioequivalence, they may have enough lead time to file an IPR first to determine whether the brand patent is valid. This approach could save costs in the long run if the generic can save research and development costs or possibly enter the market sooner. This will jeopardize the exclusivity period, but the generic may be the only company ready to enter the market thereby, in effect, obtaining market exclusivity.

- NCE-1 Cases

If the patent is on a new chemical entity, the generic may not be able to file a Paragraph IV certification because the brand manufacturer has five years of exclusivity from the date of the first NDA approval. In such a case, ANDAs most likely will not receive approval until the end of the exclusivity period. In this situation, it may make tactical sense to file an IPR rather than wait out the five years of exclusivity. Again, the same consideration regarding the loss of the exclusivity period must be considered.

Protecting the Brand

If an IPR or PGR is filed, the patent owner is at a significant disadvantage. This is because the petitioner has had unlimited time to prepare for and draft the petition; whereas, the patent owner has only 90 days to respond. As a result, brand manufacturers must take steps early on to protect their products by developing affirmative evidence of patent validity, such as the existence of any secondary indicia of non-obviousness. Aside from preparing for a potential IPR or PGR, companies also should review their prosecution strategies to make certain that any patents filed contain both broad and narrow claims. They should also consider maintaining pending continuations in order to obtain later filed claims that read directly on the commercial product at issue in any litigation. In the past, it was advantageous for pharmaceutical companies to seek claims that were as broad as possible. This created a greater likelihood of an infringement suit later on. Now, companies must also consider whether their claims are too broad to survive a challenge in a post-grant proceeding before the USPTO.

Budget

The USPTO filing fees for an IPR are $23,000 and for a PGR are $30,000. The budget for an IPR or a PGR can vary greatly depending on the firm, the number of claims to be challenged, whether experts are needed, the scope of discovery, and whether the case settles and when. The total cost of an IPR or PGR may range from $200,000 to $750,000 or possibly more. An IPR should be less costly than a PGR because the number of potential challenges is lower. For the petitioner, the drafting of the petition is a significant front-end cost generally in the $100,000 to $150,000 range, exclusive of experts and search fees. This is because the petition sets the stage for the entire litigation and must be strong enough to warrant the PTAB instituting a trial. In contrast, a single patent litigation in district court averages at least $2 million. See AIPLA Report of Economic Survey (2013), p. 34.

The Time to Strategize Is Now

Pharmaceutical companies have a new weapon in their arsenals when looking at ways to increase or maintain market share in today’s competitive environment. The USPTO post-grant procedures should always be a part of the strategy when a company is considering entering the market with a product that may potentially infringe existing patents, when a company is engaging in costly research and development and there may be time to challenge the validity of an existing problematic patent, or when a generic is considering entering a market and has a strong validity challenge against the brand patent.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.