In pharmaceutical litigation conventional wisdom teaches practitioners to focus on active ingredient patents over other types of patents that cover, for example, formulations and methods of use. A review of Federal Circuit and district court decision success rates

While active ingredient patents are the most likely to survive validity and infringement challenges, relying solely on these patents has significant disadvantages for patent owners. Active ingredient claims cannot always reflect the innovative advantages of a pharmaceutical product, such as a new use for a known substance or a formulation that enables delivery of a known drug into the body at desired rates and amounts.

Also, formulations and methods of use may be developed after the active ingredient and therefore be entitled to patents that expire later than the active ingredient patent. Further improvements to formulations or methods of use may provide additional and extended patent protection for a brand name company.

On the other hand, while a generic company may need to exhaust resources to develop a noninfringing formulation, it may have a better chance of invalidating patents that claim subject matter other than an active ingredient. Generic manufacturers may under certain circumstances also avoid method-of-use patents by limiting the indications for which they seek to market their product.

Brand Name v. Generic Success Rates

Since KSR the Federal Circuit and district courts issued final decisions on the merits

District court decisions were also closely divided, with brand name companies having a marginally better success rate than in the Federal Circuit. Post-KSR, district courts issued final decisions on the merits for 54 pharmaceutical products.

Table 1: Decisions on the merits by drug product

Pharmaceutical patents may be categorized as claiming (1) drug substances or active ingredients; (2) pharmaceutical formulations or compositions; and (3) methods of use;

As expected, active ingredient patents provide the most effective protection for brand name companies, but “other” patents, namely formulation and method-of-use patents, provide significant protection.

Federal Circuit Results

The Federal Circuit issued decisions on the merits for 16 pharmaceutical products that were protected by active ingredient patent claims.

The active ingredient patents can be further divided into sub-groups: claims for new active ingredients or molecules, and claims for specific forms of an active ingredient such as polymorphs, isomers, or salts. New molecules provided the best results for brand name companies while generic manufacturers were more successful designing a noninfringing product or invalidating the narrower active ingredient claims (polymorphs, isomers, salts). In the active ingredient category, four generic successes involved polymorphs, isomers, or salts.

The other 22 products considered by the Federal Circuit after KSR were protected by formulation or method-of-use claims, or both, but were not protected by active ingredient claims. Out of 14 products that were protected by formulation patents, the brand name prevailed on only three— a 21 percent success rate.

Formulation patents can also be divided into sub-categories, including formulations for oral administration, injectable or other liquid formulations, combinations that contain more than one active ingredient, and formulations that allow delivery of an active ingredient at a particular rate or to a certain area of the body. Interestingly, formulation patents relating to liquid pharmaceutical products (e.g., injectables, sprays, drops) were more difficult for generic challengers to overcome.

Finally, when considering only method-of-use claims, the Federal Circuit ruled favorably for the brand name on two out of seven products—a 29 percent success rate. All generic successes on method-of-use claims were based on invalidity/unenforceability.

And, the brand name prevailed on one product that was covered by both formulation and method-of-use claims. Table 2 summarizes the results.

Table 2: Federal Circuit decisions on the merits by type of patent claims asserted

Overall brand name companies had a 75 percent success rate in cases that involved active ingredient claims versus a 29 percent success rate on products that had only formulation and/or method-of-use claims. Although cases involving non-active ingredient claims were more challenging, they accounted for six out of 18 brand name companies’ successes in the Federal Circuit.

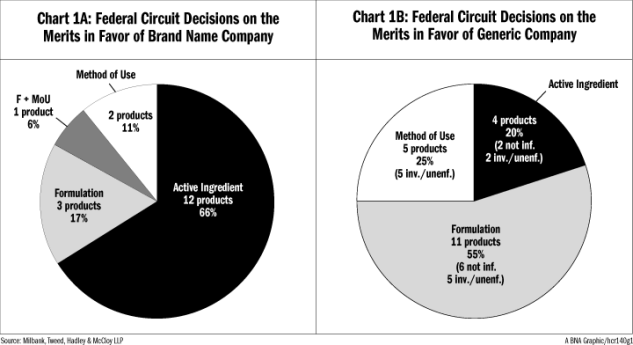

Chart 1A illustrates the 18 products where the Federal Circuit ruled in favor of the brand name company, grouped by the type of patent claims considered by the court. Chart 1B illustrates the 20 generic company wins at the Federal Circuit.

Chart 1A shows that active ingredient patents account for two-thirds of successful patent cases for brand name companies, while the other categories (formulation and method-of-use patents that do not have active ingredient claims) account for one-third of all successful patent cases. Viewing the Federal Circuit decisions in this manner shows that patents other than active ingredient patents have value to brand name companies.

On the other hand, Chart 1B demonstrates that the chances of success for a generic company increase significantly when active ingredient patents are not at issue.

District Court Results

The district courts issued decisions on the merits in favor of the brand name company for 15 out of 20 products that were primarily protected by active ingredient patents

Cases that related to polymorph, isomer, or salt patents accounted for three of the generic companies’ five successes. In the remaining two cases, the Federal Circuit reversed.

Brand name companies achieved higher success rates for formulation patents and method-of-use patents at the district court level than at the Federal Circuit. The brand name prevailed in seven out of 16 formulation patent cases—a 44 percent success rate.

Out of the nine generic successes, five were based on noninfringement and four on invalidity/unenforceability. The district court results, like the Federal Circuit, showed that formulation patents relating to liquid pharmaceuticals fared better than other formulation types.

When only method-of-use claims were asserted, the brand name succeeded in four out of 10 cases—a 40 percent success rate. Again, in all six method-of-use cases where the generic manufacturer prevailed, the patent in suit was invalid or unenforceable.

Finally, the brand name succeeded in three out eight cases where district courts considered both formulation and method-of-use patents—a 38 percent success rate.

Overall, brand name companies had a 75 percent success rate in the district courts when asserting active ingredient patent claims—the same success rate exhibited in the Federal Circuit. Products that fell into the “other” patent categories had a 41 percent district court success rate, which is better than the 29 percent success rate in the Federal Circuit.

Table 3 summarizes the results.

Table 3: District court decisions on the merits by type of patent claims asserted

Table 3 shows that formulation and method-of-use patents provided significant victories for brand name companies at the district court level. Nearly one-half (14 out of 29) of the district court decisions in favor of brand name companies did not involve active ingredient claims.

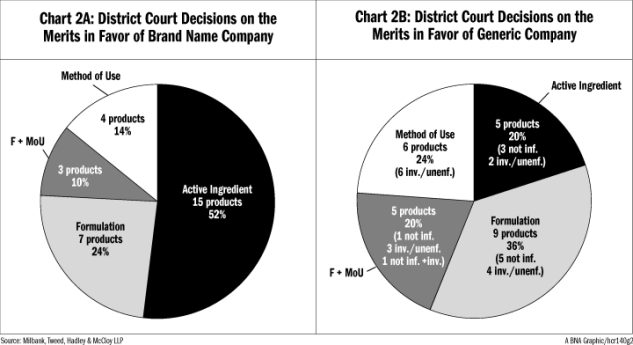

Chart 2A illustrates the 29 products where a district court ruled in favor of the brand name company, grouped by the type of patent claims that were asserted. Chart 2B illustrates the 25 generic company wins in the district courts.

On the district court level, the active ingredient successes account for 52 percent of successful patent cases for brand name companies while the “other” categories account for 48 percent of successful cases, once again highlighting the value of non-active ingredient patents.

District court case results are a good indicator of how a case will be resolved on appeal. The Federal Circuit reviewed appeals relating to 30 post-KSR district court decisions on the merits.

The appeals court reversed on the merits in five cases (17 percent rate of reversal). In three of the reversals a district court ruling in favor of the generic challenger was reversed by the Federal Circuit. In the remaining two reversals the Federal Circuit’s decision favored the generic manufacturer.

Are Some Patents “More Valid” Than Others?

The likelihood of success in patent litigation depends on the strength of the patent in terms of the scope and breadth of the patent claims when compared to the prior art (validity) and to a competitor’s product (infringement). While infringement is a highly product-specific inquiry, previous validity decisions can shed light on trends that litigants can consider when preparing their case and assessing their chances of success for each of the three categories of patent claims.

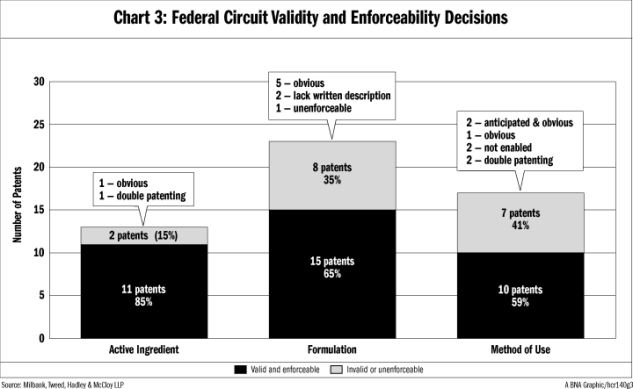

Not surprisingly, at the Federal Circuit level, active ingredient patents are more likely than other pharmaceutical patents to survive an invalidity or unenforceability challenge. As shown in Chart 3, since KSR the Federal Circuit addressed validity of 13 active ingredient patents and decided that two (15 percent) were invalid or unenforceable. For comparison, the Federal Circuit decided that eight out of 23 (35 percent) patents with formulation claims were invalid or unenforceable and seven out of 17 (41 percent) patents with method-of-use claims were invalid or unenforceable.

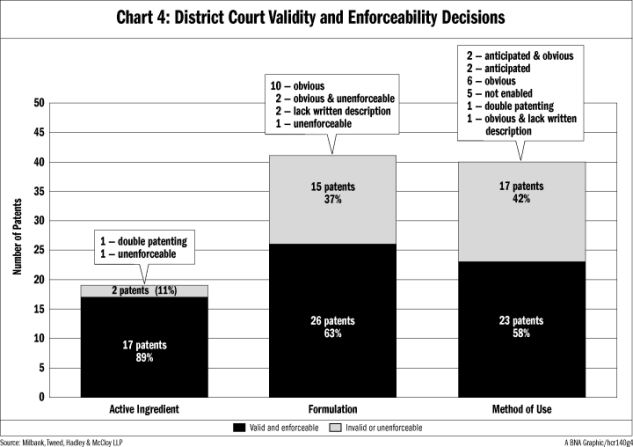

Active ingredient patents also fared better in the district courts. Out of 19 active ingredient patents considered by the district courts after KSR, only two (11 percent) were found invalid or unenforceable. For comparison, 15 out of 41 (37 percent) patents with formulation claims and 17 out of 40 (42 percent) patents with method-of-use claims were held invalid or unenforceable by the district courts.

What Makes a Successful Formulation Patent?

As shown in Chart 3, the Federal Circuit favored validity for 15 of 23 (65 percent) patents that claimed pharmaceutical formulations. Of the eight that were invalid or unenforceable, the Federal Circuit determined that five patents were invalid for obviousness, two patents were invalid for lack of a sufficient written description and one patent was unenforceable.

As shown in Chart 4, the district courts ruled in favor of validity for 26 out of 41 (63 percent ) formulation patents. Out of the remaining 15 that were invalid or unenforceable, 10 were determined to be obvious, two were obvious and unenforceable, two lacked a sufficient written description, and one was unenforceable.

A review of the Federal Circuit’s obviousness inquiries for formulation patents shows that the court appears to focus on proofs regarding whether the prior art guides a skilled person toward a limited number of solutions that can be systematically tried. As addressed in more detail below, the Federal Circuit held that the patents in Bayer v. Barr

On the other hand, in cases like In re Omeprazole Patent Litigation

These cases highlight that a product’s development history and what was available to a person of skill in the art at the time of the invention are critical when developing validity challenges and defenses relating to formulation patents.

In Bayer the Federal Circuit determined that the patent at issue was obvious because a person of ordinary skill in the art had only a narrow list of possibilities to choose from for developing the claimed formulation. Drospirenone, the active ingredient in the oral contraceptive Yasmin, was known in the prior art.

Bayer’s patent related to a formulation containing micronized drospirenone in a “normal” (non-enteric coated) pill. Micronizing drospirenone improved its rate of absorption, but also led to undesired isomerization in the stomach, which Bayer claimed taught away from using a normal pill formulation. Isomerization could be prevented by using an enteric coated formulation, but it would likely reduce bioavailability and increase patient-to-patient variation.

Bayer argued that the prior art taught away from using a normal pill and the successful results obtained with a normal formulation were unexpected. Even so, the Federal Circuit found that the prior art directed a skilled person to two options for formulating the product: an enteric coated pill and a normal pill. In light of the two options, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that using a normal pill was obvious to try and therefore the patent was invalid. In this case, the generic challenger successfully framed the options available to a skilled person as a simple choice between only two possible paths.

In Purdue there were more than two options for making the claimed formulation, but the Federal Circuit still held that patents relating to a controlled-release tramadol formulation (Ultram ER) suitable for once-daily dosing were obvious. The court focused on a prior art patent that listed tramadol as one of 14 compounds that could be used in a once-daily controlled-release formulation.

The district court and Federal Circuit rejected Purdue’s characterization that there were “scores” of possible active ingredients (or combinations thereof) disclosed in this prior art patent. Once again, the generic challenger successfully limited the options to a simple list available in the prior art.

On the other hand, in cases where obviousness challenges were overcome, the court considered the lack of guidance regarding what options to choose in combination with then-available information that taught away from the claimed formulation. For example, in In re Omeprazole the Federal Circuit found that the prior art did not narrow the field of possible options and upheld the validity of two patents directed to formulations that included an enteric coating, a water-soluble/water-disintegrable subcoating, and a “core” containing the active ingredient and an alkaline reacting compound.

The active ingredient in Prilosec (omeprazole) was invented in 1979, but developing an oral dosage form of the drug presented significant challenges. The prior art disclosed that while an enteric coating could protect the omeprazole from degradation in the stomach, it also contained materials that would cause compounds like omeprazole to decompose during storage.

The prior art also showed that while the problem with formulating omeprazole might be solved by adding an inert water-soluble subcoating to protect the active ingredient from degradation caused by the enteric coating, it raised additional problems relating to degradation during manufacture and untimely delivery when ingested. Unlike in Bayer and Purdue, the courts rejected arguments that the claimed formulations were obvious.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that a skilled person working to solve the stability problems had multiple options to pursue regarding each element of the formulation to address the various problems faced by the inventors and would not arrive at the claimed formulation without hindsight and/or undue experimentation.

One reason the court decided In re Omeprazole differently than Bayer and Purdue may be the extensive treatment of the prior art references in In re Omeprazole showing a large number of options that in some cases taught away from using the claimed combination, as well as the existence of alternatives and teaching away in prior art relied on by the generic challengers.

New formulations can be the subject of New Drug Applications under

Fortical was a 505(b)(2) NDA which in turn referenced the more common 505(b)(1) NDA for the product Miacalcin. The active ingredient in all three products (Fortical, Miacalcin, and the ANDA product) is salmon calcitonin, which is easily degraded by body fluids, relatively unstable in pharmaceutical compositions and is poorly absorbed through tissues.

The patent in suit was directed to the Fortical formulation and used a different preservative, absorption enhancer and surfactant than the earlier Miacalcin formulation.

The Federal Circuit treated Miacalcin as a “reference composition”—analogous to a “lead compound”—to determine if the changes made to obtain Fortical were obvious.

The court noted that although prior art references mentioned using citric acid, none of the references focused on it for the same purpose as in the Fortical® formulation, did not suggest the claimed concentration, and did not provide a narrow list of materials that could be systematically tried. As in In re Omeprazole, the Federal Circuit determined that the prior art did not lead a skilled person to use citric acid in the Fortical® formulation in the normal course of research and development and rejected the invalidity challenge.

Comparing Bayer and Purdue with In re Omeprazole and Unigene emphasizes the importance of addressing the state of the art at the time of the invention and the possible avenues of product development available to a person of ordinary skill. A limited number of options to try to solve a particular problem favors the patent challenger.

On the other hand, a patentee can improve their chances of success by developing the facts relating to issues faced by the inventors during development through both internal documents and prior art.

What Makes a Successful Method-Of-Use Patent?

As noted in Chart 3 above, 17 Federal Circuit decisions addressed validity of patents that claim a method of use and seven of those decisions resulted in invalidity or unenforceability. The Federal Circuit’s grounds for striking down these patents were more varied than in its formulation patent decisions: two patents were anticipated and obvious, one patent was obvious, two were not enabled, and two were invalid for obviousness-type double patenting.

The district court decisions were likewise varied. As shown in Chart 4, the district courts issued opinions on 40 patents that claim a method of use and struck down 17: two were anticipated and obvious, two were anticipated, six were obvious, five were not enabled, one was invalid for obviousness-type double patenting, and one was obvious and lacked a sufficient written description.

One area of increased litigation over the past few years are method-of-use patents where the active ingredient was known in the prior art, but was later discovered to be useful for treating a particular condition. In these cases the court reviews whether a person of ordinary skill in the art would expect that the particular active ingredient would be effective for the claimed indication, and whether there were known problems or side effects associated with the drug or class of drugs that taught away from using it for a particular indication or even as a pharmaceutical product.

For example, in Eli Lilly v. Actavis

In Eli Lilly v. Actavis, the Federal Circuit addressed a patent that claims a method for treating attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder by administering an effective amount of atomoxetine to a patient in need of treatment. The patent in suit issued 15 years after a patent claiming atomoxetine itself.

At that time, however, atomoxetine was studied for the treatment of urinary incontinence and depression (without success). The Federal Circuit noted that the initial suggestion that atomoxetine might be effective to treat ADHD “was met with skepticism,” that similar compounds exhibited negative effects, and that “experts for both sides were in agreement that they would not have expected that atomoxetine would be a successful treatment of ADHD.”

Based on this evidence, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision that use of atomoxetine to treat ADHD was not obvious to a person of skill in the art. Here, as in In re Omeprazole and Unigene, the court looked to the expectations of a skilled person at the time of the invention.

In Eli Lilly v. Teva, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision that patents relating to the osteoporosis drug Evista were valid. The patents were directed to a method of inhibiting bone loss in post-menopausal women or treating post-menopausal osteoporosis comprising administering a single daily oral dose of an effective amount of raloxifene hydrochloride.

Raloxifene, the active ingredient in Evista, was previously known and tested for treating breast cancer and autoimmune disorders. The district court and Federal Circuit noted that osteoporosis and autoimmune disorders are very different conditions and a person of skill in the art would not expect that the same compound could be successfully used for both.

In addition, existing information taught away from using raloxifene because it was believed to have significant bioavailability problems. Later studies, however, showed that raloxifene prevented bone loss.

Based on the state of the art at the time of the invention, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that it was not obvious to a skilled person to use raloxifene to treat osteoporosis and that the method-of-use patents were valid.

On the other hand, in King the Federal Circuit addressed two method-of-use patents relating to the muscle relaxant Skelaxin. The patents related to a method of increasing the bioavailability of the active ingredient (metaxalone) by administering an oral dosage form with food, or by informing the patient that taking the drug with food increases its bioavailability.

Like in Eli Lilly v. Actavis and Eli Lilly v. Teva, the active ingredient in the pharmaceutical product was known in the prior art. Unlike in the two Eli Lilly cases, the product at issue was previously sold for the same indication as in the patents in suit. In addition, prior art disclosed that administering metaxalone with food decreases gastric upset.

The district court granted Eon’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity because it determined that increased bioavailability was an inherent result of taking metaxalone with food (as disclosed in the prior art). The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s anticipation analysis, stating that metaxalone was used for decades to treat muscle pain and that it was known to administer the drug with food.

Method-of-use patents have also been invalidated for obviousness-type double patenting. In these cases the courts held that the method-of-use claims were invalid because they were not patentably distinct from the disclosures of earlier active ingredient patents and there was no terminal disclaimer. The court’s analysis highlights that method-of-use patents need to disclose a use for the product that is sufficiently different from previously disclosed uses.

For example, in Sun v. Eli Lilly

That patent’s specification also mentioned that gemcitabine could be used to treat cancer. The court invalidated the patent in suit based on this disclosure and explained that an inventor cannot receive a patent on a composition of matter that discloses its uses in the specification, and later extend the patent term by obtaining patents that claim these same uses.

Similarly, in Pfizer v. Teva

Litigants developing strategies relating to method-of-use patents should also consider possible enablement challenges and whether the patent disclosures will permit use of the claimed methods without undue experimentation. The inquiry generally relates to the indications disclosed in the patent, the amount of testing that is in the specification or was available at the time of the invention, and dosage information provided in the patent.

In Eli Lilly v. Actavis, discussed above, the Federal Circuit determined that a patent specification that contained statements that atomoxetine was useful for treatment of ADHD, and supporting human testing that was completed shortly after the application was filed but not included in the specification met the enablement requirement. The Federal Circuit noted that in cases where the priority date is not in dispute, post-filing evidence can be used to substantiate utility statements that are already in the specification. In contrast, in In re ’318 Patent Infringement Litigation

The district court held that the specification did not demonstrate utility because relevant animal testing was not complete at the time the patent issued and that the patent did not provide sufficient dosage information to teach a skilled person how to use the claimed method.

Affirming the district court’s decision, the Federal Circuit explained that patents cannot claim “a mere research proposal” and that typical patent applications need to be supported by test results, even if they are in vitro or animal tests. The key difference between Eli Lilly v. Actavis and this case appears to be the inventor’s testimony that she was not sure galantamine would work when she submitted the patent.

Given this admission and the lack of testing noted by the district court, the Federal Circuit held that the patent did not satisfy the enablement requirement.

Conclusion.

Although active ingredient patents remain the strongest protection from a brand name company’s perspective, Federal Circuit and district court statistics show that brand name companies have significant success asserting formulation and method-of-use patents, even though validity decisions on these patents are split between brand name companies and generic challengers.

A review of the case law assists in analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of potential invalidity arguments for formulation and method-of-use patents and in assessing the chances of maintaining or invalidating these types of patents.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.