More frequently than ever before company executives, company inhouse counsel, as well as outside counsel are asking: What is a patent or patent portfolio worth? Recent years have seen the development of a patent marketplace with a growing array of monetization options. We addressed a number of these monetization techniques in our earlier article regarding patent monetization from a lawyer’s perspective.

Patent transactions are now widely reported in the press, including transactions with billion dollar price tags. This has caused many companies to focus more on the question of valuation of their patent and other intellectual property assets to make sure they are not missing the opportunity offered by today’s more robust patent marketplace.

This article discusses the basic task of valuation from a lawyer’s perspective. That is, what do lawyers need to know in order to help their clients answer the often challenging question of “what are our patents worth?” For the executive, this article provides a useful overview of patent valuation issues.

What is Valuation?

Valuation of intellectual property is an estimate of how the patent owner benefits or can benefit from the intellectual property. This can include looking at the value generated by blocking others from using the patented technology, the value of licensing patents and/or the value of selling patents.

The complexity and difficulty of patent valuation is widely recognized.

As with the valuation of a business itself, it is not realistic to expect a precise answer that is unvarying and unchallengeable. A reasonable expectation is to obtain an objectively supported valuation range at that particular point in time where decision-making by the patent owner is enhanced.

Valuation depends on the strength of the patent itself, including how broadly the claims are written, whether it is easy to design around those claims, as well as whether the patent is susceptible to invalidity challenges.

The valuation may also depend on how the patents may be used by its owner, and a patent may have different value to different parties. For example, if a patent owner is using its patents in its products, the patents may deter others from copying the patented features. This can give the company value that is hard to quantify since it us unknown how many competitors were deterred. However, a valuation expert can develop a valuation model that assigns value based on projections of the sales of or costs of producing a company’s product with and without the feature (or with our without competitors having the same feature). If the patent owner is willing to allow others to use its patents, and in some fields the patentee may have little choice (i.e., patents related to industry standards), the valuation calculus could also include what others would pay for a license or sale of the patents.

Valuation may be time and circumstance dependent as well. The value of a portfolio in a forced liquidation can be different from the value of developing a thorough monetization program in litigation or licensing. Factors such as the remaining life on the portfolio or whether third parties have a need to license or buy the technology can rapidly change. The question of whether a patented technology is being used in the market, close to market or a long way away from widespread use will impact valuation.

Determining the value of a patent ordinarily differs from determining damages in litigation. While consideration of patent litigation damages may be part of a valuation, a full valuation of a patent usually is a broader exercise.

The tasks may merge if there is only one or a limited set of infringers and the patent owner itself does not use the patent. However, even in that case the valuation would differ from calculating damages in litigation because a good valuation model would have to account for the risk of losing and the expenses of enforcement. One study put patent owner overall success rate in litigation as low as 32 percent.

Why Valuation?

Before considering valuation, one must understand the client’s objective. Is the valuation needed to secure a loan or for some other financial valuation? In such case, the task may not be the question of what is the value of my patents, but the more limited task of determining if the patents are worth more than a threshold amount.

Further, if the company is not using the patents and has a need for fast monetization, the question may be what the patents are worth if they were to be sold in X number of months (6-12 months is a realistic marketing period for selling portfolios in the United States). Valuation of patent rights is often needed in bankruptcy, sales transactions, to develop licensing or litigation programs, for financial reporting, for tax reasons, in divorce proceedings, to obtain venture capital, to securitize loans, to know the exit strategy from investments in nascent companies and in merger, acquisitions and other corporate transactions. The more central the patent rights are to the deal, the issue of valuation becomes more important.

Some may be tempted to skip the step of valuation by putting the patents on the market to test the licensing value or sale value. However, this can yield a result where the patents are sold too cheaply or the expectations are set too high for management of the company.

A valuation that is thorough and understandable is a powerful tool in a negotiation with a third party. If the third party is infringing the patent(s), you are in the difficult position of asking such party to pay something they have already. If no one is using the patents, you need to explain the benefit to the third party of adopting the technology. In either case, a sensible valuation helps reach common ground as to reasonable deals that can be made regarding use (or purchase) of the subject patents.

Valuation is often needed for effective decision making in business transactions, consideration of monetization options, litigation decisions and for tax planning. Valuation may also play a role in evaluating the effectiveness of research and development efforts or patent prosecution strategy. If the company is not developing strong and valuable patents, this may indicate that a change needs to be made to current practices and direction. In some cases, if the valuation of patents shows there is very little value, it may impact decision-making as to whether to continue to pay for the maintenance of such patents in the United States and abroad.

Market Data on Patent Valuation

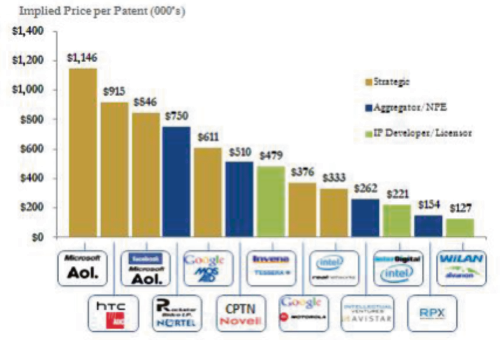

The range of valuations we have seen from public sales transactions as collected by Ocean Tomo is all over the map, which makes the case for individualized valuation:

The above transactions may not be typical since they involve the sales of larger portfolios which may raise questions about whether the price per patent is atypically high or low. Further, many patents will have little or no value if they are not utilized on the market and are unlikely to be adopted.

Further, the royalty rates for licensing patents can vary from small one-time payments to larger running royalties as a significant percentage of net sales. Generally, the more important the patent portfolio is to a product the higher the royalty. In some circumstances, a portfolio is so essential to a field that it can stop accused infringers from selling any commercially viable products without a license. In other fields, for example a smart phone, hundreds of patents may cover various aspects of a product (e.g., semiconductors, audio compression, video compression, GPS features, Internet features, etc.).

The Valuation Process

Valuation experts use three broad categories to describe valuation techniques:

1. Income approach—The present value of future cash flow taking into account the risk in achieving such cash flow. This may also include the more complex question of what is the value of keeping the patents exclusive or semi-exclusive for the patent owner’s products.

How much money can be made with IP? This can include consideration of the licensing or sale potential of a portfolio. It alternatively could assess how much extra income a company can make by using the patented technology by either increasing revenue or lowering costs. The projected income should be discounted by the risk that that income will be achieved.

2. Cost approach—Consideration of how much it costs to develop the patented technology or avoid it.

A legitimate way to think of value, particularly when purchasing or licensing-in patents, is to ask how much it would cost to develop a comparable noninfringing product either from scratch or by designing around the patents. Understandably, if a patent portfolio is easy to design around, the value is low. On the flip side, the value of truly blocking technology is high.

3. Market approach—What have others paid for similar patents in similar circumstances?

This approach relies on pricing based on the sales of comparable patents, much like in the real estate market. There are two challenges to the market approach. First, sale and licensing activity related to intellectual property is rarely public information. On occasion, companies will report significant deals to the marketplace to comply with government regulations, but ordinary deals are usually confidential.

Second, even when public information can be collected, it is hard to prove a deal is comparable. The strength of patent portfolios in the same technology can vary greatly and the business circumstances surrounding a historic transaction can quickly change. For example, consider 1) the effect that the remaining life of the patents (patents generally expire 20 years after filing) can have on value even if all other factors were equal between two portfolios, 2) the circumstance where a first patent portfolio was sold at a premium to a new comer in an established market, or 3) additional information found in a detailed review make transactions that appeared to be “comparable” no longer fit into this category.

The techniques discussed above are not exhaustive of the factors going into valuation. For example, a patent owner may also derive value from a patent portfolio by having a certain amount of patents for reputational enhancement or as a deterrent to others asserting patents against the patent owner based on the existence of the portfolio.

Evaluation of Patent Strength and Risks

Thorough evaluation of the strength of a portfolio will refine a valuation. It can also be used to determine what type of discount rate may be used to account for risk.

An experienced patent practitioner can evaluate likelihood of infringement and validity. As to infringement, there are some patents where infringement can be shown without much investigation. Others will require reverse engineering of competitors’ products. Still others may require documentation that is only in the hands of the accused infringers. As to validity, a patent search may give you some idea of the risk of invalidity.

However, be warned that if a patent is asserted in litigation and the stakes are high, the amount of effort that an accused infringer will put into invalidating the patent often cannot be reproduced on the more limited budget that may be available for a valuation exercise. For example, an accused infringer may search for prior art in all countries of the world, engage experts, look for obscure publications or products and other such scorched earth tactics. The limitations usually put on the diligence can, therefore, hamper the certainty of the resulting valuation, particularly for smaller portfolios.

There are some objective factors that can be considered during valuation. For each of these factors, you need to evaluate how much they tell you about the patents being valued:

- How many patents are needed to make a product in the industry? Are the patents being evaluated blocking technology or optional technology?

- Does the patent owner have any obligation through participation in industry standard setting to license the patents on reasonable terms and conditions?

- How often are the patents being cited by other patents? This may indicate that the patent is very basic. However, it could be that one party just cited the same patent over and over as a matter of routine.

- How much prior art is cited in the patents being valued? This may indicate that a diligent search was made and that most relevant prior art is cited. However, even if hundreds of references are cited, this may not capture the most significant prior art if the search methodology was flawed.

- Are some applications still pending in the portfolio? This is often considered very valuable (especially in the form of continuations and continuations-in-part) because the portfolio can be fixed if the claims are too narrow to cover products on the market or if new prior art is found.

- How large is the portfolio or how many claims in the patents? Generally, the larger the portfolio and the more claims, the less risk that the entire portfolio may be invalidated. However, there are some very large portfolios where only one or two claims are infringed. These issues have to be triaged to understand a large portfolio. Further, the cost of maintaining a large portfolio is high due to patent office maintenance fees. This cost should be taken into account in a valuation.

- How long is left on the patents’ life? If the life of the patents is short and there is no current use of the patents on the market, the value may be low.

Tips on Getting Started

Team: The best team for a valuation project may include employees of the company requesting the valuation, a valuation professional and an attorney who can evaluate the merits of the patents. Employees in the pertinent field may have the best information on the market, competitive analysis of third party products, comparable licenses and other critical information. A valuation expert will be able to consider the best techniques to use and the data to be collected inside and outside the company, and perform the valuation calculations. A lawyer can provide data on patent strength and risks.

Then, the next step, states Roy D’Souza, managing director of Ocean Tomo’s valuation practice, “is to clearly identify (i) the exact IP that is included in the project (as many projects are completed in phases, and care must be taken when including pending applications and numerous international geographies if applicable,); (ii) the parties that will be reviewing the report now and potentially in the future; (iii) confirmation of the timing in which the valuation must be completed; and (iv), most importantly, the exact purpose for which the valuation is going to be used. It is very rare for companies to complete a valuation of their portfolio as a ‘nice to have’. There are always very specific intended uses and based upon who is requesting the analysis (e.g., patent aggregator vs. strategic operating company), the value consideration can vary greatly.”

Information: No matter the approach chosen, the more data that can be obtained the more certain the valuation. If the strength of the patents has been tested in a contested proceeding or litigation, this will be a better data input to a valuation where the patents are merely presumed valid and infringed. If one can find several comparable internal and external licenses, this will also enhance the valuation. If market size and future trend information is available this will enhance the valuation. The collection of a substantial information by a company before engaging patent and valuation professional will reduce the costs of evaluation and will likely improve the accuracy of the results.

While market value information is hard to get, there are some good sources for general royalty rate information such as surveys by Licensing Executive Society and certain treatises, and in third party database sources (e.g., ktMINETM). Further, IP attorneys or valuation experts may have a general sense of what rates might be applied based on the technology area and from basic information about the patent and markets. However, the individual portfolio and market has to be deeply understood to really evaluate how prior comparable deals should be taken into account.

Larger Portfolios: A large portfolio of patents may need to be triaged to find the strongest patents. Further, a valuation case will be most persuasive if there is evidence the patents are in current use or can add value to a business if used. This task can be quite significant if no data on the use or potential use of the patents exist. Tackling this task can be done by reviewing the patents carefully and collecting (or obtaining, e.g., reverse engineering) evidence of use or potential use.

Data driven techniques may also be used instead of or in combination with substantive review. Data can be obtained from public sources such as the websites for United States or other patent offices. Some data that is publicly available that may be useful in valuation is how often a patent is cited by other patents, whether certain competitors patents have recognized the patents that are being evaluated and the number of patents of similar vintage in the primary classifications for the patents. If technical articles cite to the patents being evaluated this may give some data as well. There are software programs and outside services that can collect data that may be useful in considering patent strength as well.

Budget: This will largely depend on the client’s monetization goals and the likely value. Since the amount of effort, in part, depends on the ultimate answer of value, valuation can be taken in stages. A rough valuation may be obtained by looking at the market size and likely use of the patents. This may be refined by consideration of who is infringing the patents and the infringers’ sales. If the circumstances justify a deeper look, more refined information may be sought. Generally, this can be an iterative process when cost and the amount of effort are in question because the value is very uncertain.

Privilege Considerations: One consideration is whether aspects of a valuation prepared by a lawyer will be privileged.

Conclusion

Valuation issues have become increasingly important in the patent world. Today’s patent lawyers must have a good understanding of valuation in order to assist their clients understand what their patent assets are worth. If lawyers understand the basics, they can better interface with their clients and valuation experts to improve the valuation process and marshal the facts that are necessary to make the valuation persuasive.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.