The US Patent and Trademark Office dramatically shifted its administrative tribunal’s mandate in the early months of the Trump Administration, limiting the number of patent challenges judges review and repositioning the board to be less central to intellectual property disputes.

Acting Director Coke Morgan Stewart has reversed Biden-era guidelines to restrict the path for patent validity challenges and created a new policy routing those reviews through leadership before they’re considered on the merits, among myriad other changes to the office’s procedures.

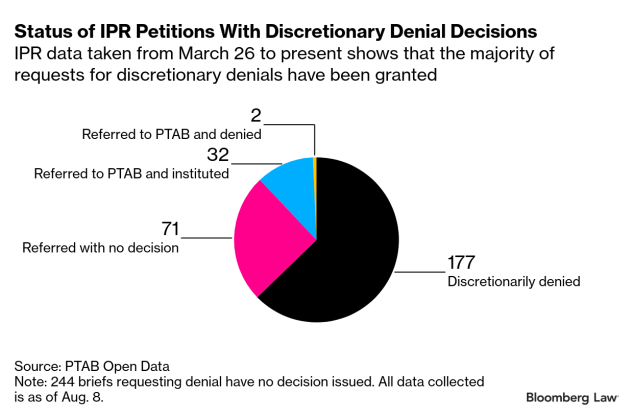

Since those changes, Stewart has thrown out more than 60% of the nearly 300 petitions she’s reviewed, citing discretionary factors, while referring just over one third to Patent Trial and Appeal Board judges for review on the merits.

Patent attorneys say they’ve scrambled to adjust, carefully studying agency decisions to better tailor their petitions and altering strategies on the fly.

“People are rethinking whether to even try the Patent Office right now,” Cyrus Morton, patent attorney at Robins Kaplan LLP, said.

Critics of the shift say it’s weakened the PTAB, cutting off access to an essential cog in patent infrastructure at the expense of infringement-lawsuit defendants, who turn to the tribunal to cut down what they argue are invalid patents asserted against them. Tom Krause, a former PTO solicitor, said the policy shift “completely subverts” the PTAB’s purpose.

But proponents argue the changes are overdue and properly rein in a board that’s been described by patent owners as a “death squad” for their IP. Steve Schreiner, an attorney from Carmichael IP who represents patent owners at the tribunal, said the agency has taken “the thumb off the scale” against them.

“The system’s been kind of out of whack at least since 2019,” Schreiner said. “This starts to make it, just maybe, I won’t say reasonable, but not so onerous and seemingly unfair to patent owners.”

President Donald Trump’s nominee to lead the agency, John Squires, told the US Senate in May the PTAB was in “need of reform” and the patent system writ large was going in the “wrong direction.” But the agency under Stewart—a patent attorney and former PTO chief of staff—hasn’t waited for his confirmation to kick start the transformation.

The PTO declined to comment for this story.

‘Major Rebalancing’

The 2011 America Invents Act established the PTAB to have technical experts adjudicate patentability disputes faster and cheaper than generalist courts.

But the PTO’s changes since Trump took office in January are likely to shift many of those patent fights back to courts, multiple attorneys said.

Stewart’s March memo bifurcated the PTO’s consideration of inter partes review petitions—challenges to patents’ validity—filtering them through the director to consider whether to reject them out of hand based on a range of discretionary factors, some of them new. Any patent owner facing an IPR can now request discretionary denial from the director before it’s considered on the merits.

Since March 26, 526 respondents have sought discretionary denial, and Stewart has issued 282 decisions as of Aug. 8. She granted denial requests for 177 of them, referring 105 to judges. Just 200 IPRs have been instituted this year in that time period compared with 274 during the same time last year.

“Anything that can ratchet down your exposure at the PTAB is generally a good thing,” said Brad Close, a patent owner and executive at Transpacific IP Group Ltd.

Jamie Simpson, chief policy officer and counsel at the inventor-focused Council for Innovation Promotion, said the “major rebalancing” underway at the PTAB is more in line with the law that created it. Patent owners invest significant resources and time securing inventions that are challenged as soon as they become valuable, she said.

“Being subject to multiple challenges in different fora, and seeing inconsistent decisions, is tilting the playing field against innovators to such a degree that the overall system is becoming less effective,” Simpson said.

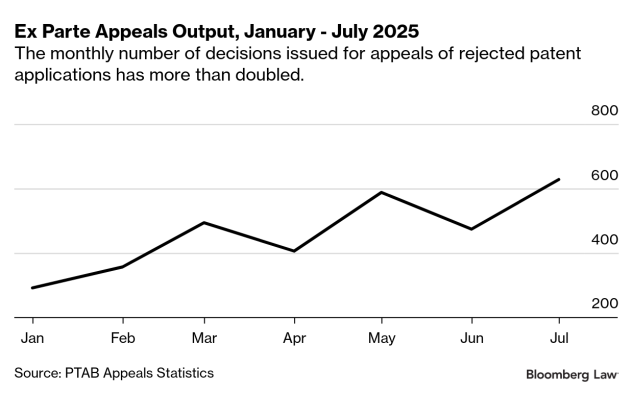

PTO leadership has shifted PTAB judges’ time and resources towards more appeals of rejected patent applications. In April, Chief Judge Scott Boalick told judges to boost their appeals output to roughly 500 decisions a month, from roughly 350, while shrinking timelines to issue decisions in under 12 months.

Judges have exceeded that goal: The PTAB issued 628 appeals decisions in July, more than double the 292 it produced in January, according to PTO statistics.

Two judges granted anonymity said the changes are pushing the PTAB further away from IPRs, demonstrating executives’ intentions to adjust the board’s purpose.

But reducing the number of patent challenges can have long-term consequences, said Joe Matal, a former acting director who helped establish the board. Patents that aren’t innovative are often asserted by people “out there to make a fast buck,” he added.

Alex Moss, executive director of the Public Interest Patent Law Institute, said a “weaker PTAB” leads to lower quality patents and ones that are “demonstrably invalid.”

“That means more monopolies, less competition, higher prices, less economic dynamism,” she said.

Uncertainty

Stewart’s March memo instituting the interim discretionary denial process provided an open-ended slate of factors, including whether other forums have adjudicated the patents’ validity; compelling economic, public health or national security interests; and “any other considerations.”

Attorneys say they’ve looked to Stewart’s decisions to understand how she’s implementing those factors.

Some, such as the patent owner’s “settled expectations” in avoiding challenges to their longstanding intellectual property, have left attorneys facing uncertainty, said Trey Powers, co-chair of Sterne Kessler’s PTAB trials practice.

“There was sort of a settled expectation about how PTAB proceedings work,” Powers said. “That settled expectation has been altered.”

ArentFox Schiff patent attorney Ehsun Forghany said the flurry of changes means litigation strategies are subject to change day to day.

“We may have been planning to file an IPR in one case, and three decisions later it no longer makes any sense to file that IPR,” he said.

To contact the reporter on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.