The federal outer continental shelf (OCS) has generated a large amount of America’s oil and gas production, but each platform eventually reaches the end of its useful life. OCS leases require that the improvements be decommissioned when the term expires. Decommissioning, the return of the leased property to the condition required by law in an environmentally sound manner, is expensive and difficult. A January 2016 Government Accountability Office (GAO) study reported an estimate of $38.2 billion in future decommissioning costs for the Gulf of Mexico region alone.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) within the Department of the Interior, which regulates OCS oil and gas leasing, requires lessees to furnish surety bonds or other security to guarantee these costs. In most cases, decommissioning will not occur until years or decades after the leases originally impose the duty, but the costs to furnish the required security and pledge the accompanying collateral are immediate, substantial and ongoing.

This combination of high exposure, high expense, and long time periods has made for a strong exchange of views among companies, regulators and legislators on financial security. When BOEM sought last summer to step up its scrutiny and security requirements, many industry participants objected strenuously. In the wake of the November 2016 election, several members of Congress urged that the enhancements be rescinded and re-examined in the new administration. On Jan. 6, 2017, the agency suspended application of the new rule as to leases with multiple lessees, but required lessees that are solely liable on their leases to comply on schedule.

The decommissioning task remains a certain future liability, regardless of how much financial assurance is mandated in advance. While the cost and other impacts of increasing the security levels have been much discussed, there have been fewer contributions to a broader public understanding of why the security is being sought in the first place. This article describes the context—in Part One by detailing the security requirements and current controversy, and in Part Two by providing background on what decommissioning is and why the scope, liability and expense are of concern to lessees, government representatives and the public.

Part One: The Controversy Over Security Requirements

On July 14, 2016, BOEM issued a Notice to Lessees, NTL 2016-N01, which became effective on Sept. 12, 2016. The NTL overhauls regulations found at

The significant shift

OCS leases require lessees to provide a base surety bond that affords a first level of credit support for a range of obligations over the life of the operation, including but not limited to decommissioning. Until the NTL, specific security for decommissioning was uncommon, so long as at least one of the lessees on the lease could show the regulators that it was large and financially secure. Passing that test typically required a net worth exceeding $65 million, a total estimated decommissioning liability under 50 percent of that net worth and a satisfactory level of production or debt-to-equity ratio. The agency generally allowed such a large co-lessee to “self-insure” the obligations under the lease, up to 50 percent of its net worth. OCS leases are commonly held by two or more parties who bear joint and several liability for decommissioning costs, so lessees are potentially liable for the entire cost across multiple assets.

BOEM reported that since 2009, at least 15 companies qualified to operate in the Gulf of Mexico have filed for bankruptcy. In at least one of those cases, Energy XXI, taxpayers were at risk of having to cover the company’s significant decommissioning liabilities, which are estimated at $1.2 billion, until the December 2016 approval of a reorganization plan. More than 110 oil and gas producers have filed bankruptcy petitions since January 2015, and some OCS lessees are, and can be expected to remain, in a volatile financial state.

BOEM’s objective under the NTL was to ensure that sufficient resources are available to cover all decommissioning liabilities of a lessee under each of its leases at all times. The new policy represents a significant shift in that it takes a much more detailed look at every lessee’s financial strength. Even where the criteria are met, the NTL allows a lessee to apply only up to 10 percent of its “tangible net worth” across all OCS leases in which it holds a stake, before outside security will be needed for the remaining life of the lease.

Calculating the amount that must be secured

BOEM begins its analysis with an estimate of the costs of decommissioning each asset. The estimates for individual Gulf of Mexico and Pacific Ocean platforms are determined by the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE). Reports commissioned by BSEE to gauge those costs are available on the agency’s website.

BOEM then calculates a total amount for all the decommissioning costs of all the OCS leases on which a given company is a lessee. That figure is the reference for the rest of the analysis. This amount may be covered in whole or in part through an approved portion of the company’s net worth, with the approved quantity confusingly referred to as “self-insurance.”

If a company qualifies for an approved level of self-insurance, it may choose how to allocate it among its various OCS lease holdings. Additionally, co-lessees may enter into arrangements by which a larger company may agree to extend its approved self-insurance for the benefit of other parties. (This suggests that a market of sorts may develop, where arrangements are made for monetary or other consideration that may be less than the bond premiums and collateral costs of outside security that the smaller party would otherwise pay.) If a balance of estimated decommissioning costs remains on any lease after subtracting the allocated approved self-insurance, then the lessees must post supplemental security with BOEM.

Timing of the security reviews

BOEM will start its review with the highest-risk leases. The agency is therefore beginning with leases with only a single leaseholder responsible for decommissioning. If the suspension of the rule is lifted, BOEM would move on to leases with multiple lessees. The agency will conduct periodic reviews to determine whether additional security is necessary as the term of the lease progresses.

The five financial factors

In sizing up whether self-insurance is available, BOEM will consider five principal factors: financial capacity; projected strength; business stability; reliability; and record of compliance. The agency also reserves the right to look at other factors, including what the agency refers to as “off balance sheet” issues.

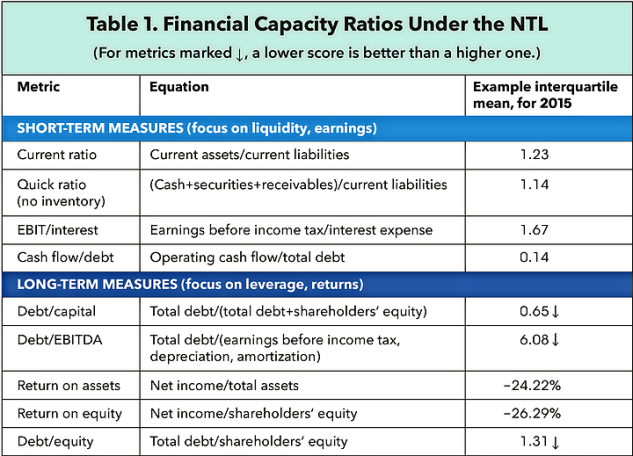

1. Financial capacity: the nine ratios

Lessees must demonstrate that they have a “financial capacity” substantially in excess of existing and anticipated lease and other obligations, as evidenced by the lessee’s most recent audited financial statements. The NTL identifies some 20 financial measures, but places principal weight on nine financial ratios described in Table 1. These ratios compare figures that are available in the lessee’s financial statements. Four of the ratios measure short-term capacity to meet obligations, focusing on liquidity and coverage for current liabilities. The other five ratios are concerned with long-term capacity, focusing on debt-equity leverages and returns on investment.

BOEM will compare the co-lessee on each of these ratios against a standard computed value using an industry sample (currently 153 rated exploration and production companies) provided by Standard & Poors. This standard is the interquartile mean of the ratio for this sample over a rolling five-year period. Thus, for 2016, the agency would look at the 2011-2015 mean after disregarding the top and bottom quartile outliers.

BOEM acknowledges there is some tension between these ratios, as a superior result on one measure may entail fewer resources to support another. To qualify for self-insurance, lessees are expected to meet or exceed the thresholds for five out of the nine ratios.

2. Projected strength: OCS value beyond the balance sheet

BOEM will consider the projected financial strength of the lessee based not only on its financial statements, but also on its rights to current production and to hydrocarbons in the ground. This factor requires a showing that the projected financial strength of the lessee is “significantly in excess of existing and future lease obligations based on the value of [the lessee’s] existing OCS lease production and proven reserves for future production.”

BOEM will allow both existing production and 25 percent of proven reserves to be used to augment a lessee’s net worth. In calculating the proven reserves, the agency will consider either a fair-market value approach or the PV-10 approach used by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

3. Business stability

BOEM evaluates the business stability of a lessee by looking at whether that lessee has had five or more years of continuous operation and production of oil, gas or sulfur in the OCS, or in the onshore oil and gas industry. This criterion is intended to predict a lessee’s stability by measuring its operational experience. However, BOEM itself recognizes that there may be exceptions to the reliability of this predictor, such as when a large and well-capitalized entity has recently entered the oil and gas sector or acquired assets through an acquisition.

4. Reliability

The reliability of a lessee is based on its credit rating from Moody’s, Standard and Poors, Dun & Bradstreet, or trade references. The minimum credit rating that a lessee must have in order to apply for self-insurance on a sole liability property is A3 (Moody’s) or A- (Standard and Poors). BOEM will also use this criterion to adjust the percentage of self-insurance allowed for any lessee. This criterion is somewhat redundant, since the rating agencies look to the same concepts that lie behind the other four factors.

5. Compliance

BOEM will view a lessee’s record of compliance with the leases, BOEM and BSEE regulations, and other applicable laws and permits. The agency recognizes that some infractions are more serious than others. It will therefore review the overall operating history of a lessee and concentrate on larger infractions.

Lessees, and members of Congress, strike back

Industry’s reaction to the new financial assurances policy was swift and largely negative. Furnishing additional security is especially difficult for smaller companies, which often must pay a premium on the bond as well as post collateral equal to 100 percent of the bond amount. Several commenters predicted that many small players will be forced to sell their assets to larger companies better positioned to meet the significant costs of supplemental bonding—assuming capacity for that bonding is even available in the market. Commenters predicted that the expensive requirements would result in reduced competition for leases. Some opined that mandating supplemental bonding could drive some companies into bankruptcy if they are unable to comply or sell their assets—thus accelerating the liabilities that the government is seeking to manage. A group of trade associations representing operations in the Gulf cautioned, “BOEM has now changed the rules in a manner that threatens to trigger the very risk it is trying to protect against.”

Larger companies with higher tangible net worth have more complex responses to the security mandate, which may not require them to post outside security. Those that have long since sold assets but remain in the chain of title are benefited by the security mandate imposed on the current lessees. The security mandate can also shift some of the financial burdens implicit in using one company’s balance sheet to cover all of the lessees’ obligations.

An underlying concern is the extended time period over which the financial security tests must be met. The rules, whether new or old, do not make significant distinctions between the imminent decommissioning of an old field that is almost exhausted, and the far-off decommissioning of a new block that is just entering production with good prospects and access.

In addition to the strong negative reactions by industry, members of Congress have taken note of this major shift in policy. In December 2016, House and Senate members urged Interior Secretary Sally Jewell to instruct BOEM to reverse or suspend the policy in favor of a more measured approach. Lawmakers from both houses called the NTL “unduly burdensome and unnecessarily punitive.”

As noted above, BOEM has now called a temporary halt to implementation of the NTL for leases with multiple lessees. With a new administration, it is possible these appeals by Congress and industry will result in a reversal or change of the policy to avoid some of the potentially harsh consequences. Focus may be concentrated on small lessees, and on lessees who are not the operator of the production unit associated with the lease.

Part Two: Decommissioning 101

Whether the NTL is unfrozen, modified, rescinded or left suspended, the decommissioning job will remain. What are the decommissioning obligations in the first place—what are the tasks and exposures with which the security discussions are concerned?

The following summary focuses on federal law. However, a variety of state and local laws may also be implicated, especially relating to onshore disposal of decommissioned assets and other shore-based activities.

As stressed above, decommissioning can be a very expensive proposition. Platform dismantlement projects can be engineering marvels, because of the depth of the water in which the platforms and wells are constructed and the short seasonal windows when work can safely proceed. For example, in the Gulf of Mexico, hurricane season generally extends from June 1 to November 30, and requires additional precautions in the types and design of mooring equipment. During years in which several hurricanes form in the Gulf, cumulative effects from the hurricanes on oil and gas operations can be significant, including structural damage to fixed production facilities.

Removal is also an environmentally sensitive undertaking. Dismantlement typically requires either explosives or mechanical means using underwater divers or drones. Removal by any method, whether mechanical or explosive, causes turbidity and loss of established hard surfaces and functioning habitat that, at many platforms, has been colonized by large numbers of invertebrates and fish. Explosives have the added risk of shock waves and acoustic energy that can kill or harm marine species and disrupt or damage marine life near the platform structure.

What is decommissioning? Is it the same as “plugging and abandoning,” or “abandonment”?

“Decommissioning” is the ending of oil, gas, or sulfur recovery operations and returning the lease to a condition that meets government requirements (

“Plugging and abandoning” is a subset of decommissioning concerned with the wells themselves. “Well P&A” typically involves filling the well with fluid, removing downhole equipment, cleaning out the wellbore, plugging open-hole and perforated intervals at the bottom of the well, plugging casing stubs, plugging annular space, placing a surface plug and injecting fluid between plugs. “Abandonment” by itself usually refers to one method of decommissioning, namely leaving the asset in place—but only after the necessary engineering and environmental precautions are taken and the necessary regulatory approvals secured.

How do co-lessees allocate responsibility for decommissioning?

The 2015 American Association of Professional Landmen (AAPL) model form Operating Agreement for Offshore Deepwater obligates the operator to perform the decommissioning activities, and allocates costs for decommissioning based on each participating interest. The Association of International Petroleum Negotiators (AIPN) 2012 model Joint Operating Agreement, an agreement commonly used outside of the U.S., similarly provides that decommissioning costs are borne by the parties in accordance with their interests. Purchase and sale agreements often allocate the lease and operating agreement liabilities between the buyer and seller.

Larger operators in the U.S. are supplementing the AAPL model form with more robust decommissioning clauses that impose specific obligations on the parties, such as indemnities, funding escrow accounts, and providing security to guarantee performance. Thus, larger co-lessees have been seeking protections similar in nature to the NTL requirements, if not to their full extent.

How are platforms and pipelines decommissioned?

The conductors between the wells and the topsides are usually dismantled first. To remove the conductor casing, operators can choose to sever it with explosives or mechanical cutting, pull and section it in 40-foot long segments, or use a crane to lay down each casing segment in a staging area and then offload it at a port for onshore disposal.

Once the conductor casing is removed, the platforms, templates and pilings are removed. First, the topsides are dismantled and lifted onto barges using a derrick crane. The next and most expensive demolition step is removing the jacket. Divers use explosives, torches or abrasive technology to make the bottom cuts on the piles 15 feet below the mudline. Then the jacket is removed either in small pieces or in a single massive lift.

Pipelines and utilities (for example, power cables) can often be abandoned in place if they do not interfere with navigation or commercial fishing or pose an environmental hazard. The operator must flush the pipeline with water and disconnect it from the platform and fill it with seawater. The open end is then plugged and buried three feet below the seafloor and covered with concrete.

After all equipment and infrastructure are removed, the operator performs a site clearance, surveying to identify any debris left behind by the removal process and any environmental damage. Remote operated vehicles or divers then remove any additional debris identified, and test trawling verifies that the area is free from potential obstructions.

What planning time and permits are required for decommissioning?

Project management, engineering and planning for the decommissioning usually start three years before the well is finally abandoned. Likewise, permitting related to decommissioning of a platform can take three years to complete. The federal agencies potentially include BOEM, BSEE, National Marine Fisheries Service, Army Corps of Engineers, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Environmental Protection Agency, Coast Guard and the Department of Transportation’s Office of Pipeline Safety.

State and local agency permits may also be necessary. For example, plans for onshore disposal or recycling of equipment may require state approvals, as may decommissioning of any shore-based pipelines, use of ports, and staging, assembly and storage areas.

What are the alternatives to complete and immediate removal?

Platforms may be converted to artificial reefs in lieu of complete removal when a state artificial reef program is in place. Under the federal Rigs-to-Reefs program, BSEE may “grant a departure from the requirement to remove a platform or other facility and allow partial structure removal or toppling in place so that the structure can be converted to an artificial reef.”

To qualify for the program, there must be a state agency that will accept title and liability for the reefed structure under a state program. Presently, all five Gulf states have adopted artificial reef legislation; these programs are in active use, with close to 500 chartered sites offshore Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida. California has enacted legislation establishing such a program (known as AB 2503), but no lessees have relied on its provisions to date.

Proponents of the reef program cite the abundant marine life that grows up and thrives around an offshore platform, and the loss of habitat that occurs when subsea structures are removed. The benefits of partial removal include preservation of existing biodiversity and habitat, and may include recreational opportunities such as diving and fishing. In addition, the state programs generally require the oil companies to remit half the cost savings from foregoing full platform removal to the state. That money can then be used by the state—for example, to fund ocean conservation and management programs.

The other alternative to immediate removal and decommissioning is the renewable energy and alternative use program permitted by the Energy Policy Act of 2005. The Act allows structures to remain in place following the conclusion of oil and gas activities so that they can be used for “energy-related purposes or for other authorized marine-related purposes.” Structures may be used for a variety of purposes, such as research, recreation, education, renewable energy production, telecommunication facilities, and offshore aquaculture, before being removed. However, when the structure ceases to be used for these approved alternative uses, complete removal is still required (unless it is approved for partial removal under the Rigs-to-Reefs program discussed above). Oil and gas lessees would remain responsible for financial security for decommissioning during the extended time periods when the alternative use is being conducted.

Promisingly, scientists, industry and some regulators are exploring evolving techniques to evaluate the ecological costs and benefits associated with complete removal compared with various leave-in-place alternatives. These comparative assessment methodologies seek to better account in decommissioning decision-making for the ecosystem services, particularly habitat value, provided by this subsea infrastructure. More consistent and predictable availability of alternatives to full removal could substantially drive down decommissioning costs, which could, in turn, be factored into the regulators’ calculus as to the magnitude of financial security required.

What is the framework for financial security requirements?

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act provides the Secretary of the Interior with the authority to require bonds or other forms of financial assurance for decommissioning, rents and royalties, and other financial obligations (except oil spill financial responsibility, which is covered by the Oil Pollution Act (OPA)).

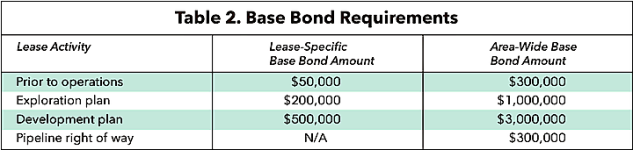

There is a two-stage approach to satisfy BOEM financial assurance requirements. The first stage is the base bond, which covers all types of lease obligations (except OPA liability), extends beyond the end of the lease, is required of all lessees, and can be lease-specific or area-wide. These are set bond amounts depending on the lease activity, as illustrated in Table 2.

The base bonds expire seven years after the termination of the lease, six years after completion of all bonded obligations, or after termination of any litigation related to the bonded obligation, whichever occurs last.

The second stage is the supplemental bond, which provides additional coverage for lease obligations, and is canceled after decommissioning is completed and BSEE certifies clearance of outstanding payments. The only exception to cancellation of the bond once decommissioning and other outstanding lease obligations are fulfilled is if BOEM determines that the future potential liability resulting from any undetected problem is greater than the amount of the base bond. In this case, BOEM may notify the surety that the agency will wait seven years to cancel all or part of the bond. It is the supplemental bond requirement that provides the basis for the financial analysis and security mandate revised in the NTL discussed in Part One.

What types of financial security are accepted?

A lessee can use multiple instruments to satisfy its security requirements, and can arrange for a “tailored plan” through BOEM that may rely on other forms of acceptable security. The security may be phased in over a period of months, but generally needs to be completely in place within one year of the security mandate.

Conclusion

BOEM touched a raw nerve in July 2016 by increasing the scrutiny and the security required of OCS lessees. The January suspension of the rule as to multiple-party leases gives time for a new administration to take a fresh look at the issues. 2017 may see some reduction of the requirements through further executive branch action. But the decommissioning jobs that lie ahead are real and substantial, and industry and government representatives need to address the funding of those tasks. The alternatives to complete removal can often create tangible environmental and economic benefits, and should be explored and pursued in parallel with the evolution of the financial standards.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.