Infrared Cameras in Oil, Gas Operations

• Cameras are used by industry, regulators to detect volatile organic compound and methane emissions.

• Oil, gas industry generally accepts use of cameras as tools for leak detection but raises concerns about frequency of use, data validation.

The infrared cameras that the oil and gas industry use to make invisible hydrocarbon emissions visible are on the brink of becoming more widespread, as regulators promote their use under proposed rules and settlements.

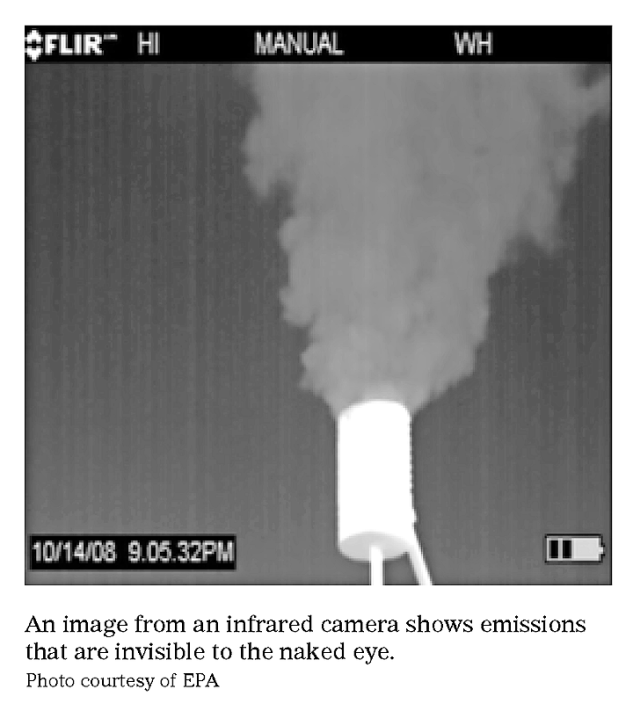

They can’t detect how much or what kind of emissions—such as the potent greenhouse gas methane or ozone-forming volatile organic compounds—are pouring from oil storage tanks, pipelines or industrial facilities, but they can draw attention to potential violations and hazards by making a plume obvious.

Companies say they have been using the cameras as a screening tool for years, which has helped them to detect leaking natural gas that can then be captured and sold.

But the cameras have limitations that would be exacerbated under unforgiving rules or consent decrees, critics say. Not only are the cameras costly at $120,000 a piece, but questions have been raised about data accuracy and frequency of use.

There is wide acceptance that infrared cameras for leak detection are “the wave of the future—it’s the iPhone era for compliance,” said Brooks M. Smith, an environmental and natural resources law partner at Troutman Sanders. But companies’ voluntary use of such technology is “a far cry” from a requirement under a rule or settlement, he told Bloomberg BNA.

The cameras also are a tool for environmental groups to raise public awareness of leaks. EarthWorks used the camera to show images of the massive methane leak at a Southern California Gas Co. storage facility in Aliso Canyon, near Los Angeles, which displaced thousands of people and released an estimated 94,500 tons of methane 47 ER 569, 2/19/16, 33 DEN A-3, 2/19/16, 32 ECR, 2/18/16.

“For us, what we’ve seen is we spend less time fighting about, ‘Is there a problem?’ and now the focus goes to, ‘What can you do about fixing it?’ It’s starting to chip away at these emissions,” Bruce Baizel, the oil and gas accountability project coordinator for Earthworks in Durango, Colo., told Bloomberg BNA.

Cameras Used for Screening.

Oil and gas companies have been using the FLIR—forward-looking infrared—cameras routinely for about five years, said Scott Janoe, a partner with Baker Botts in Houston, who has worked on regulatory compliance issues in oil and gas exploration and production enterprises.

“Like any tool, my clients and others want to make sure it’s used correctly, and by that I mean an infrared camera is best used as a screening tool, in other words, to identify that there may be emissions,” Janoe said. After the initial screening, other tests are needed to determine the contents and size of a leak and whether a facility is in compliance with its permit, he said.

Jonah Energy has been voluntarily using infrared cameras for more than five years in its natural gas field in Wyoming to detect methane emissions, company spokesman Paul Ulrich told Bloomberg BNA.

“We’re quite proud of our program,” he said. “It helps reduce our maintenance costs and helps increase our product volumes by capturing more emissions,” he said.

Oil and gas operators are doing their own surveys with the cameras to make sure equipment is operating properly and training employees in correct work practices, Richard Alonso, a partner at Bracewell LLP who represents oil and gas companies, told Bloomberg BNA.

“This is an area where EPA and the states advertising what they were going to do has really woken people up. The word’s out, and there’s a lot of companies that are being proactive,” Alonso, a former EPA official for Clean Air Act enforcement, said.

Concerns About Rule Requirements.

The cameras themselves aren’t a burden for the industry, Janoe said; the problem could be how frequently and where operators would be required to use them under the regulations.

“When you’re talking about unmanned facilities, oftentimes in very rural areas, very far off the beaten path, it becomes a question of cost-benefit analysis when you’re choosing how frequently a remote place would be subject to such screening,” he said.

In a comment on the EPA’s proposed methane rule for new and modified oil and gas sources, Alvyn A. Schopp, chief administration officer and regional vice president and treasurer at Antero Resources Corp., said his company didn’t oppose the use of infrared cameras as a screening tool to find potential emissions sources, but said other technology still would be needed to quantify emissions to determine whether any violations have occurred.

Brooks said the cameras must be properly used to ensure the data they create are accurate.

“I think what EPA does is use cameras as a first screen to see if they need to look more closely and then gather more compliance data,” Smith said. “That seems like a good idea to me. Working smarter not harder.”

Cameras Cost $120,000 Each.

Infrared cameras, which cost about $120,000 apiece, are prohibitively expensive for small operators, the Independent Petroleum Association of America and the American Exploration and Production Council, both representing independent oil and gas explorers and producers, said in comments on the proposed EPA methane rule.

Companies that don’t buy the cameras can contract with services that use them.

The IPAA is concerned the EPA would require the cameras in regulations that remain in place for years, locking industry into one expensive way to detect emissions that might not prove to be the best approach in the long run.

“Our basic argument to them is, you really need to let the states evolve their programs more and let the industry learn more about the management of these fugitive emissions before you lock in a costly, demanding regulatory system for a long period of time,” Lee Fuller, executive vice president of the IPAA, told Bloomberg BNA.

Use by Regulators in Colorado.

Colorado in 2014 became the first state to require the oil and gas industry to detect and reduce emissions of methane. The state required leak detection monitoring for drilling and production processes and inspections of large emissions sources 37 State Environment Daily, 2/25/14, 45 ER 605, 2/28/14, 37 DEN A-5, 2/25/14, 37 DER A-43, 2/25/14, 36 ECR, 2/24/14.

The state’s Air Quality Control Commission said in the regulation that oil and gas operators already were using many technologies and practices to reduce emissions of hydrocarbons in a cost-effective way, including infrared cameras.

The rule says the cameras are an example of approved instrument monitoring methods that companies can use to detect leaks. But it added in the regulation that it “anticipates that many operators will choose to utilize IR cameras, in light of their relative ease of use and increased reliance by both by industry and regulators within Colorado and across the country.”

The Colorado rule requires operators to make quarterly or more frequent leak inspections at most operations 46 ER 2812, 9/25/15, See previous story, 09/24/15, 185 DEN A-7, 9/24/15, 185 State Environment Daily 185, 9/24/15, 184 ECR, 9/23/15.

Doug Flanders, director of policy and government affairs at the Colorado Oil and Gas Association, told Bloomberg BNA the cameras are a good tool producing useful data. Industry operators and contractors have been using them properly, and there haven’t been objections to their use, he said.

The key issue is that camera operators must be well trained, so they can identify real leaks and distinguish them from steam or other harmless emissions, Flanders said.

Cameras Proposed in EPA Methane Rule.

At the federal level, the EPA is calling for use of the technology in its proposed first-ever methane emissions standards (RIN 2060-AS30) for new oil and natural gas wells 46 ER 2481, 8/21/15, 30 TXLR 813, 8/20/15, 160 DEN A-1, 8/19/15, See previous story, 08/19/15, 159 ECR, 8/18/15, 22 ECB 278, 8/31/15.

The EPA proposed that new and modified well sites and compressor stations conduct fugitive emissions surveys twice a year using optical gas imaging technology, such as infrared cameras, and repair leaks within 15 days of when they are found.

The proposed rule also asks for comment on annual or quarterly monitoring with the equipment. The proposal calls for the frequency of subsequent surveys to decrease or increase, depending on whether fugitive emissions are found.

One advantage of the cameras is that they can survey a big area such as an entire storage tank, instead of just the usual points where leaks may occur, said David McCabe of the Clean Air Task Force.

“We think it’s a really useful technology,” he said. The cameras can point out emissions, he added, but only enforceable national standards such as the EPA’s proposed methane rule can reduce them.

BLM Proposal Calls for Cameras.

In addition to the EPA rule, the federal government has proposed use of the cameras under a Bureau of Land Management rule.

The proposed rule to reduce methane leaks from oil and gas activities on federal and Indian lands (RIN 1004-AE14) would require infrared cameras or other monitoring devices for operators of 500 or more wells within a bureau field office jurisdiction. Operators with fewer wells may use portable analyzers instead 47 ER 326, 1/29/16, See previous story, 01/28/16, 18 DEN A-7, 1/28/16, 17 ECR, 1/27/16, See previous story, 01/25/16, 14 ECR, 1/22/16.

The BLM said in the proposed rule that infrared cameras are the most effective way to detect leaks but are more expensive than portable analyzers, which are instruments that use a variety of methods to detect hydrocarbon leaks from individual pieces of equipment.

EPA Plans for Cameras in Settlements.

The EPA also has said it will require technology such as infrared cameras in settlement agreements when appropriate.

“They really want to push the technology,” Alonso said. The use of the cameras in settlement agreements gets the technology out into the field.

The EPA in September issued a compliance alert to help oil and gas storage vessel operators assess whether their systems are able to prevent emissions. The notice mentioned Noble Energy’s use of infrared cameras to monitor vapor control systems, which was required under the most high-profile case to date involving the cameras.

In the 2015 settlement, Noble agreed to fix its vapor control systems on storage tanks in the Denver-Julesburg Basin and then monitor with the cameras to make sure they are working properly. The EPA estimated the Noble settlement would cost more than $70 million to resolve.

The EPA says it wants to see advanced monitoring with tools such as the cameras included in settlements whenever appropriate under its Next Generation Compliance strategy, which is the agency’s initiative to increase compliance with environmental regulations through the use of pollution monitoring and information technology and improvements in the design of permits and regulations.

“The way that enforcement is tackling the oil and gas industry is definitely by using these advanced technologies—the infrared cameras and other kinds of emission monitoring devices,” Alonso said.

Objections to Enforcement Tool.

Dana Stotsky, a former EPA attorney who was assigned to the Noble Energy case, said the agency used infrared cameras in building its case 30 TXLR 441, 4/30/15, 46 ER 1223, 4/24/15, 78 DER 78, 4/23/15, 78 DEN A-16, 4/23/15, 78 State Environment Daily, 4/23/15, 77 ECR, 4/22/15.

“You can’t see it with the naked eye, and then you see it with the camera, and it’s unmistakable,” Stotsky, who left the agency in 2014 and is now a partner in Jacobs Stotsky PLLC, told Bloomberg BNA.

Colorado’s Department of Public Health and Environment, which worked with the EPA on the case, reported at the time of the settlement that volatile organic compounds were detected during inspections in 2012 when the department had just begun to use infrared cameras for leak detection.

R. Peter Weaver, vice president of government affairs of the International Liquid Terminals Association, which represents companies that operate bulk liquid storage terminals for products including crude oil and refined petroleum products, objected to the use of the cameras for enforcement.

In comments to the EPA about its national enforcement initiatives, which included an attempt to reduce air toxics emitted from liquid storage tanks, Weaver wrote: “While advanced monitoring techniques may prompt an inspector to conduct further review in conjunction with a specific facility, ILTA objects to the agency’s suggestion that current technology for remotely detecting emissions can be correlated directly to a discrete regulatory violation. ILTA cautions the agency against the use of inconclusive observations as a speculative basis for enforcement.”

“It’s an imagery that doesn’t prove anything, doesn’t demonstrate anything, but it looks really scary,” Weaver told Bloomberg BNA. “I guarantee you it’s going to cause them to pull on all kinds of strings they never would have harassed people with in the first place. It’s a tool that has a lot of potential for abuse.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Renee Schoof in Washington at rschoof@bna.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Larry Pearl at lpearl@bna.com

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.