Tens of thousands of chemicals are produced or imported annually into the U.S. and other industrialized countries. Many of these have been detected in the environment and yet have not been well-characterized with respect to environmental fate or potential human health or ecological effects.

Lately, the term “emerging contaminants” (ECs) has been used to describe contaminants with increasing scientific, regulatory or public concern, but either health-based standards are lacking, or existing standards are being reassessed. The presence of a mixture of such chemicals in environmental media, especially in drinking water, often leads to rapid regulatory actions and public outcry, despite the lack of comprehensive understanding of potential risks to humans or the environment.

There often are disparate and conflicting state and federal regulatory agency actions and opinions on these emerging contaminants. This inconsistency is a significant challenge to private industry, especially those with EC uses, products and emissions with an environmental footprint in multiple states.

This challenge is perhaps most acutely present for municipalities that are seeking to regain the public trust regarding chemicals present in drinking water that do not present a risk to human health. It often is challenging to track which emerging contaminants should be included in monitoring programs, difficult to understand why a certain chemical has been included or excluded from the target list and, even more so, perplexing to know what, if anything, is subject to legal action or should be done proactively to best mitigate public, environmental and corporate risks to changing chemical regulations.

This article explores the current status of emerging contaminants regulation in the U.S., with a focus on the approaches and actions implemented across the 50 states and the District of Columbia. We first define emerging contaminants and then discuss federal programs that provide the backdrop against which state programs are developed. State programs are compared and contrasted and a case study of EC regulation is presented.

What Is an Emerging Contaminant?

There is no consistent definition for emerging contaminants across federal or state regulatory or public health agencies. In fact, the term also is referred to as “constituents of emerging concern,” “contaminants of emerging concern,” “emergent contaminants,” or “unregulated contaminants.”

A draft white paper titled Aquatic Life Criteria for Contaminants of Emerging Concern, prepared by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Emerging Contaminants Workgroup in 2008, defines emerging contaminants as “chemicals and other substances that have no regulatory standard, have been recently ‘discovered’ in natural streams … and potentially cause deleterious effects in aquatic life at environmentally relevant concentrations. They are pollutants not currently included in routine monitoring programs and may be candidates for future regulation depending on their (eco)toxicity, potential health effects, public perception, and frequency of occurrence in environmental media.”

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) defines emerging contaminants as “any synthetic or naturally occurring chemical or any microorganism that is not commonly monitored in the environment but has the potential to enter the environment and cause known or suspected adverse ecological and (or) human health effects.”

As we look to state regulatory and public health agencies, the terms used and definitions for unregulated contaminants of emerging concern become even more variable. For example, at the 2015 Arizona Water Association Conference, the chair of the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Advisory Panel on Emerging Contaminants Outreach and Education Committee listed numerous terms and phrases that often are used without a clear understanding of the definition or distinction between terms.

The lack of consensus regarding the universal definition of emerging contaminants underscores one of the basic challenges currently surrounding their regulation in the U.S. As the first step to gaining consensus for their regulation, we propose a definition of emerging contaminants that reflects the evolving science and provides a framework for moving forward. This definition is built off the one developed nearly a decade ago by the joint Environmental Council of States and Department of Defense Sustainability Workgroup, which stated that an emerging contaminant “has a reasonably possible pathway to enter the environment; presents a potential unacceptable human health or environmental risk; and does not have regulatory standards based on peer-reviewed science, or the regulatory standards are evolving due to new science, detection capabilities, or pathways.”

We propose a further clarification of this definition:

- Type 1 ECs are chemicals without federal regulatory standards;

- Type 2 ECs are those with regulatory standards, but for which threshold values are inconsistent and changing based on new science, detection capabilities, pathways or policies.

This distinction between Type 1 and Type 2 emerging contaminants is useful when devising a risk management strategy, because it facilitates a clearer understanding of potential risks and options for truly unregulated chemicals versus those whose regulations are changing.

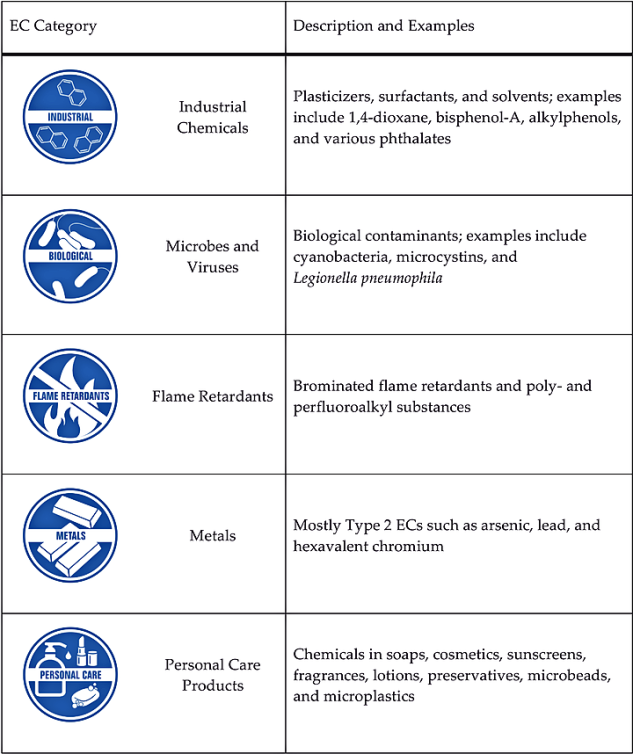

A number of emerging contaminants has been identified under state and federal agency programs. We identified the most consistently discussed emerging contaminants and grouped them into the following eight categories to provide a more holistic picture of trends and foci:

State Programs

State regulatory agencies have the delegated authority to regulate and enforce environmental and public health requirements. The 50 states have different resources and priorities and have taken different approaches to regulating emerging contaminants. Although charged with the authority of protecting public health and the environment within their jurisdictions, states often have limited resources to conduct rigorous research on toxicity and health risks, much less occurrence of ECs in the environment.

Many rely on initiatives at the federal level. Some states, however, have EC-specific programs aimed at identification, prioritization, evaluation or regulation of emerging contaminants within their state in advance of federal requirements. In fact, we are starting to see a shift, with much more state-led regulatory actions regarding emerging contaminants in the absence of federal guidance, which is resulting in a patchwork of inconsistent regulations and public health priorities.

We conducted a state-by-state survey to identify how U.S. states and the District of Columbia are addressing emerging contaminants. State regulatory initiatives for them were identified using standardized research methods and one-on-one interviews with state regulatory representatives. We reviewed state agency websites and relevant open-source documents. States were evaluated based on the level of monitoring of scientific and regulatory developments for emerging contaminants, the development of regulatory guidance or standards for them, and whether or not they had established specific programs to address human or environmental impacts from emerging contaminants in their state. The full compendium of this information is available online at http://www.integral-corp.com/capability/health/emerging-contaminants/.

Federal Guidance as a Starting Point

Federal programs often provide valuable information, guidance and resources for state regulatory and public health agencies. Perhaps the most well-known and identifiable EPA EC program is the Office of Water’s Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Program. In 1996, Safe Drinking Water Act amendments established the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR). Under this rule, EPA issues a list of no more than 30 unregulated contaminants once every five years, to be monitored by public water systems with the goal of understanding national occurrence in public drinking water. The most recently administered UCMR3 program included seven volatile organic compounds, one synthetic organic compound, six metals, one oxyhalide anion and six perfluorinated compounds. Occurrence data can be downloaded from the EPA UCMR Web page (http://www.epa.gov/dwucmr/occurrence-data-unregulated-contaminant-monitoring-rule).

So far, based on UCMR3 data, the EPA has decided that the presence of strontium in U.S. drinking water could present a human health risk and has proposed to develop a federal drinking water maximum contaminant level (MCL) for this contaminant. UCMR4 was proposed Dec. 11, 2015, and monitoring will be conducted on an accelerated schedule between 2018 and 2020. Contaminants on this list include 10 cyanotoxins, two metals, eight pesticides, one pesticide manufacturing byproduct, three brominated haloacetic acid groups, three alcohols and three other semivolatile chemicals.

The UCMR program more recently has been used by states to identify emerging contaminants in their local drinking water systems. This shift from a national program to gather occurrence information for national prioritization and regulation to a federal program that provides local-level information on unregulated contaminants (Type 1 ECs) in public drinking water has raised significant concerns. Not all public water supply systems test for emerging contaminants under UCMR; therefore, there is inconsistent coverage of potential public exposure.

Second, by definition, the underlying health effects information for the emerging contaminants that are tested under UCMR is immature and often debatable. As such, states and local water districts often rely on advisory information that is not meant to be a promulgated standard and threshold requirement, or they adopt their own regulations. This incongruent process bypasses the requirements within the Safe Drinking Water Act to assess socioeconomic impacts of drinking water regulations and also creates a situation wherein standards fluctuate and are inconsistent from one state to the next.

USGS has a prominent program for emerging contaminants that has been operational for more than a decade. The USGS Emerging Contaminant Program develops analytical methods to measure emerging contaminants in environmental media, assesses the environmental occurrence of them at national, regional, state and local scales, aims to characterize the sources and source pathways that contributes to an emerging contaminants detection in the environment, researches their fate and transport in the environment, and looks for ecological effects from emerging contaminants exposures. More information can be found here: http://toxics.usgs.gov/investigations/cec/index.php?src=QSA014.

A number of studies have been completed by USGS, including the landmark 2002 publication by Kolpin et al. published in Environmental Science and Technology that was the first national-scale analysis of emerging contaminants, including pharmaceuticals and other chemicals in U.S. streams. Currently, USGS is conducting a national study of environmental releases of emerging contaminants from landfill leachate. Although USGS has no regulatory authority, this federal agency contributes significantly to the scientific understanding of occurrence, fate and transport and serves as an important source of scientific information for state agencies.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the lead federal agency for public health in the U.S. Although not explicitly a program designed to address emerging contaminants, the CDC’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) program provides valuable information about human exposure to chemicals. Since 1999, the NHANES program has provided a continuous assessment of the exposure of the U.S. population to environmental chemicals (including regulated chemicals and emerging contaminants) and provides prevalence statistics and information on contaminant levels, paired with health information gleaned from interviews and physical examinations. Human biological samples are analyzed for more than 200 chemicals, including volatile organic chemicals, metals, pesticides, endocrinedisrupting chemicals and perfluorinated compounds. This information is useful in numerous ways; however, specifically for emerging contaminants, it helps scientists and regulatory agencies understand demographic factors that could be associated with human exposure, as well as potential links between emerging contaminants exposures and health effects.

To assist state agencies, the CDC has offered two funding opportunities for state-led biomonitoring projects through the agency’s National Biomonitoring Program. In 2009, the CDC launched the first round of funding under the State Biomonitoring Cooperative Agreement. The goal of this initial five-year project was to expand the awarded state’s capability and capacity to conduct biomonitoring of environmental chemicals. California, New York and Washington were awarded five-year grants, each splitting $5 million annually.

In 2014, the CDC announced a second round of biomonitoring grants and awarded funding to five states (California, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey and Virginia) and a consortium of four states, called the Four Corners States Biomonitoring Program (Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico).

Combined, the federal agencies within the U.S. have programs to assess emerging contaminants occurrence and potential risk in drinking water (e.g., EPA UCMR), commerce (e.g., EPA Toxic Substances Control Act), environmental media (e.g., USGS and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and the human population (e.g., CDC). Of these initiatives, only the EPA programs have regulatory authority, and these programs often are criticized for being time-intensive and unhelpful in addressing environmental concerns at the local level. Because states have the authority to implement and customize federal guidance within their jurisdictions, it is imperative to understand how state programs are addressing emerging contaminants. It is likely that state-specific regulations will continue to affect industry and municipalities most directly in the near term.

State-by-State Comparison

The majority of states do not have an explicit program directed at emerging contaminants and do not appear to address them via promulgated regulations in advance of federal programs. A limited number of states, however, have begun to address emerging contaminants by establishing specific programs aimed at identification, screening, or prioritization and evaluation. Additionally, many states now are contributing resources toward limited initiatives such as conducting occurrence studies, or setting guidelines or standards before federal values are established.

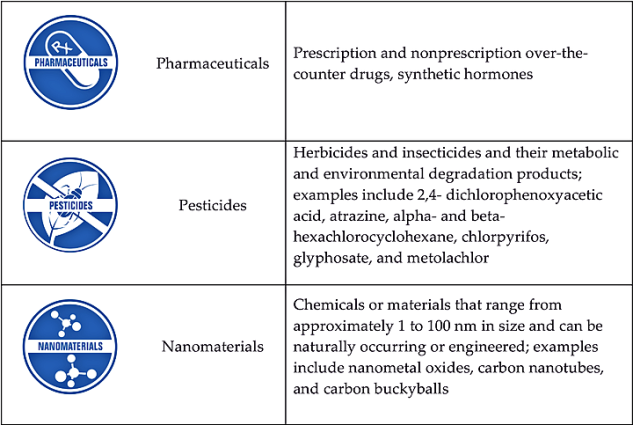

The map below shows the differences in the EC level of activity for each state, based on our survey. Inactive states almost exclusively rely on federal actions, guidance and regulations. Very active states such as California, Minnesota, Massachusetts and Maine have developed specific risk management programs addressing emerging contaminants. States listed as active or limited could have one or two initiatives that begin to gather state-specific information; however, they do not have an explicit program for emerging contaminants and do not tend to devote significant resources to these initiatives.

Arizona, California, Maine, Minnesota, New York, New Jersey and Washington all have state programs explicitly designed to address potential EC impacts to human health and the environment throughout their respective jurisdictions. For the remaining 43 states and the District of Columbia, EC-specific initiatives vary from one or two chemical-specific regulations or occurrence monitoring to only limited response actions following a site-specific driver. Just over a dozen states have no emerging contaminants program or initiatives and rely exclusively on federal actions, guidance and regulations.

State agencies are increasingly taking the initiative to gather data, usually occurrence information, to help prioritize their regulatory actions. The most commonly identified state-led initiative for emerging contaminants was environmental sampling to assess occurrence frequency and levels.

We identified more than 30 states with some kind of environmental occurrence program. We found that the most common emerging contaminants with state guidelines or standards included those that we categorized in the industrial chemical group. Approximately half of Type 1 ECs with state guidance or standards (absent at the federal level) are for industrial chemicals. Interestingly, however, the most commonly detected category of emerging contaminants is pharmaceuticals, logically found in surface waters impacted by various urban water treatment systems.

The decision-making process for prioritization and regulatory actions is often not readily transparent. From a national perspective, it can be difficult to locate and track each state’s pertinent advisories, criteria and the underlying rationale for those values. There did not appear to be a clear geographical distinction or rationale as to why some states addressed certain categories more than others; regional differences do not account for this pattern. Based on our in-depth examination into how state and federal agencies are addressing the task of deciding which emerging contaminants need assessment, how they are assessed and how regulations are promulgated, we concluded that a more consistent and transparent process is needed.

Examples of the Most Active and “Transparent” State EC Programs

Our detailed review of each state’s regulatory framework for environmental contamination and how they address emerging contaminants is best highlighted by some of the more active and transparent state programs, described below.

Minnesota

Minnesota often is identified as one of the states with the most robust and transparent processes for identifying, prioritizing, evaluating and regulating emerging contaminants. The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) has developed a drinking water program that strives to proactively develop human health-based guidance for emerging contaminants that have been found in state groundwater, surface water and soil, as well as those that have not been found or investigated in Minnesota.

The program also seeks to provide the public with information about how people could be exposed to these contaminants. Program staff screen approximately 20 chemicals and provide guidance for up to 10 chemicals every two years; these chemicals are nominated for investigation by risk managers, stakeholders and the public. Following evaluation, information sheets on these selected emerging contaminants are published on MDH’s website.

The Minnesota Department of Health is among the few agencies that have adopted a quantitative scoring system for establishing priorities for emerging contaminants. In the initial toxicity screening, data concerning emerging contaminants is compiled and ranked. The department develops comprehensive information sheets and screening profiles for emerging contaminants reviewed by their program, as well as ECs that were nominated but not selected for further review. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency also provides information on emerging contaminants for the state. For example, the agency conducts occurrence monitoring of ECs throughout the state’s surface waters. Combined, these two agencies supply Minnesota with a robust and active emerging contaminants program.

California

California has several active programs to monitor and regulate ECs throughout the state. California’s numerous agencies and programs have initiatives that either explicitly address emerging contaminants, or implicitly address them by virtue of pioneering chemical-specific regulations in advance of federal and other state actions.

For example, the California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) is tasked with setting statewide policy on the administration of water rights and water quality control. The nine regional water quality control boards are responsible for adopting and implementing water quality control plans (also known as basin plans), issuing water discharge requirements, and performing functions including water quality monitoring and control in their respective regions. These entities work together to address emerging contaminants and have developed monitoring strategies for a number of chemicals that could potentially pose human and ecological health risks.

Under the Recycled Water Policy, the SWRCB established an advisory panel to address issues regarding emerging contaminants in recycled water and maintains a list of those that are to be monitored throughout the state’s recycled water. Monitoring data for emerging contaminants can be found through the GeoTracker information system within the Groundwater Ambient Monitoring and Assessment Program, which provides detailed sample information, including location and resulting values for a variety of chemicals that have been or are being monitored.

A science advisory panel, created by the SWRCB in conjunction with the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, has issued reports with recommendations for monitoring strategies for emerging contaminants in California’s aquatic ecosystems (Anderson et al. 2010 and Anderson et al. 2012). The panel developed a risk-based screening framework to focus on select emerging contaminants based on potential adverse human health effects and their occurrence in waters receiving municipal wastewater treatment plant discharge and stormwater.

After implementing the risk-based screening framework to identify emerging contaminants for initial monitoring, the panel recommended applying an adaptive, phased monitoring approach, with guidelines to update and direct appropriate action corresponding to potential risk. The panel advised the state to promote and support research initiatives in the development of bioanalytical screening tools; identifying data gaps in the source, fate, occurrence and toxicity of emerging contaminants; and relative risk assessment. Follow-on studies based on these initial recommendations have been conducted (e.g., Dodder et al. 2015), including a statewide emerging contaminants monitoring program framework and identification of research needs.

California’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) is the lead agency for implementation of Proposition 65, or the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986. Proposition 65 provides a list of chemicals and labeling requirements to protect the state’s citizens and drinking water sources from chemicals that can lead to reproductive harms, cancer and birth defects. The list is updated at least once a year and includes around 800 chemicals, including Type 1 and Type 2 ECs. The office also develops for both Type 1 and Type 2 ECs, to aid SWRCB in the creation of regulatory standards for the state’s drinking water. Public health goals are not regulatory standards; however, state law requires the SWRCB to set state maximum contaminant levels as close to the public health goal value as possible, considering economic and technical feasibility.

Massachusetts

The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) established an Emerging Contaminant Workgroup to identify and assess public health and environmental problems with emerging contaminants and recommend agency strategies for addressing them. The workgroup composed a preliminary list of 80 emerging contaminants in 2007, of which several were prioritized for further evaluation and possible agency actions. Their initial list was based on information on the presence of emerging contaminants within the state and potential exposure pathways.

An emerging contaminants may be screened out of the Emerging Contaminant Workgroup process if other state or federal regulatory agencies are addressing the contaminant. Additionally, higher priority is given to emerging contaminants that have a more thorough toxicological profile, that occur in several different media and for which the agency can identify tangible outcomes obtainable within their jurisdiction. The MassDEP website maintains the list of priority contaminants and status reports for actions taken for each (http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/massdep/toxics/sources/emerging-contaminant-workgroup.html).

Perfluoroalkyl Substances—Case Study for State-Led Actions

One of the most infamous emerging contaminants, with ever-increasing regulatory and public attention, is perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). One of several perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASes) under EPA review, PFOA has gained recent notoriety stemming from its detection in public drinking water supplies and the lack of federal requirements, ultimately resulting in dynamic and confusing local standards. The EPA first established a provisional health advisory for PFOA in 2009 in response to a site-specific request in Decatur, Alabama. Prior to that federal provisional guidance was a major class action lawsuit against one of the manufacturers. At the time of the trial, the lack of regulatory guidance or standards led the court to require the manufacturer, DuPont, to fund a site-specific epidemiological study of the affected communities. The results of those studies, called the “C8 Health Study,” have set the stage for individual litigation.

PFOA was included in EPA UCMR3 public water supply testing between 2013 and 2015, with relatively negligible national detection frequencies (~1-2%). Media attention surrounding the DuPont trial, plus attention on the Department of Defense investigations of PFOA in drinking water and groundwater near fire-fighting units on their installations, prompted more aggressive actions from the local communities that had UCMR3 detections of PFOA in their drinking water. Some states decided to rely on the provisional guidance from the EPA, while others decided to derive their own standards, either as guidance values or as fully promulgated requirements. The disparate PFOA guidance and standards vary by 100-fold for water and range from 0.02 to 2.0 μg/L (i.e., parts per billion).

The widely variable safety threshold values for PFOA partly reflect the fact that interpretations of the underlying toxicological database for PFOA are still inconsistent and dynamic. The EPA finalized a lifetime health advisory in May 2016, prompting many states to immediately change their screening levels—what was one day deemed “safe,” the next day was considered “at risk” and communities were urged to not drink the water. Yet just a few months prior, in the summer of 2015, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry released a draft toxicological profile for PFASes, in which they concluded that the underlying toxicity database was insufficient to calculate a lifetime protective level for PFOA.

This landscape of inconsistent safety thresholds for PFOA in water has prompted confusion and distrust by the public and other stakeholders. PFOA exemplifies how emergent science could still be used by regulatory agencies as a matter of policy to protect public health and how messages of “safe” versus “at risk” are seen as a solid bright line, despite the ability for those lines to fluctuate as different interpretations are provided and the science matures.

Conclusion—Geography Matters and Act Now

It is evident that there is not a transparent, systematic regulatory process for identifying, assessing, prioritizing and making risk-management decisions related to the protection of human or environmental health from emerging contaminants. It is a challenge to identify and piece together the numerous data streams from different sources. Unless resolved, this problem will continue to manifest itself in disparate and conflicting state and federal regulatory actions and opinions on emerging contaminants and will continue to be a significant challenge to the public and private industry.

Geography matters when trying to understand EC trends and regulations. Many states are leading the charge to address emerging contaminants within their jurisdictions, while most await federal guidance. Scientific information, such as occurrence and human or environmental toxicity data, is increasingly being generated and comprehensively reviewed by state agencies in advance of federal assessments. Many of these state-led evaluations lack the scientific rigor and transparency that are implemented at the federal level. Some states will develop guidelines or standards for emerging contaminants despite significant data gaps in exposure or toxicity.

Conversely, these state programs often conduct their assessments in a much shorter time frame, using local, state-specific information and authority. The result is a patchwork of priorities and regulations based on varying data quality. Additionally, EC data gaps can be much broader than for regulated chemicals, causing agencies to apply additional uncertainty factors in the name of the “precautionary principle”; the resulting science policy decisions implemented in the face of uncertainty further drive significant variations between agencies and stringent screening levels.

Stakeholders can watch the precedents set by the most active states and understand the priorities and processes within an individual state to help navigate the impacts that changing chemical regulations could have on their business. Given recent national public and media attention on unregulated chemicals in drinking water, it is likely that there will be increasing pressure on the states, and consequently, from the states on the federal agencies, to more consistently and transparently address emerging contaminants.

Actions can be taken to ensure that stakeholders are prepared for and engaged in addressing potential risks to emerging contaminants. More and more, public participation and comment is becoming a standard step in the regulatory processes at both state and federal programs. Mapping chemical-specific trends among various states could help stakeholders understand what information is available and being used to inform decisions.

Therefore, understanding what data streams are available or are developing for a chemical of interest, understanding how various state and federal programs could utilize that data, and then engaging with those regulatory agencies to ensure a transparent and fair assessment of the science and potential risks will help stakeholders track and respond to emerging contaminants and their potential impacts.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.