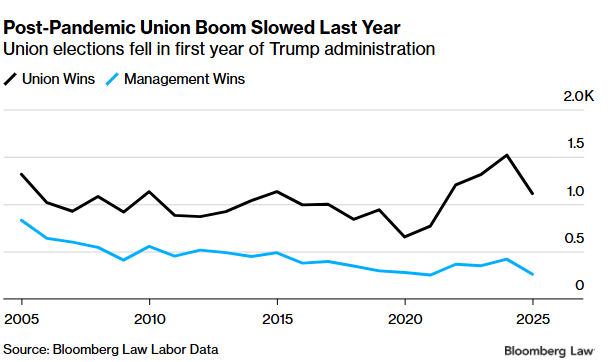

Volatile economic conditions and increasingly hostile federal oversight drove new union membership down in 2025, according to an analysis of Bloomberg Law labor data.

The number of union elections fell to 1,372 last year, down from 1,938 in 2024. That’s the fewest elections since 2021, a review of National Labor Relations Board data found. Union wins also sank by nearly 27% in 2025 compared to 2024, the first downturn since 2020. That drop in election wins led to the number of new workers organized via NLRB elections to fall nearly 40% year-over-over to just 65,542 workers in 2025, according to the data.

Organized labor saw a post-pandemic boom after decades of union membership decline. But new economic and political headwinds, including a more management-friendly NLRB and a cooling jobs market, look likely to reverse that trend. The added uncertainty could make traditional organizing more difficult heading into 2026 as workers seek stability over collective action, attorneys said.

If “your market share is shrinking and has been for decades, you ought to ask yourself whether you’re doing the right thing and if you need to do something fundamentally different,” said Marick Masters, a management professor at Wayne State University. “I think the worst thing you can do for the labor movement is try and deny these realities.”

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ annual union membership report, traditionally released in January, will likely also show a modest decline in union membership from 2024, labor attorneys said. The report has been delayed until mid February due to last year’s record-breaking government shutdown.

The 2024 edition of the Labor Department’s benchmark report found union membership stood at an historic low of 9.9% of the total US workforce, with just 5.9% of private sector workers belonging to labor organizations.

Economic Conditions

Uncertain economic conditions driven by a softening US labor market and falling consumer sentiment played a role in the organizing decline, said Louis Cannon, a partner at Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp. He noted that public approval for unions plummeted during the 2008 financial crisis.

“There was a whole lot of uncertainty this year,” he said. “I think that could make people less likely to want to unionize.”

Polling research from Gallup found in its most recent August survey that 68% of US adults approve of labor unions, down slightly from 70% in 2024. Following the Great Recession, union favorability stood at 48%, according to Gallup.

After the pandemic “there was this wave of employees whose jobs were affected by the economic shutdown in different ways, but who concluded that they needed to take a more concerted role in workplace decisions,” said Robert Combs, a legal analyst at Bloomberg Law. “The decline in union wins at the NLRB in 2025 suggests that this wave may have crested.”

Ideological differences on how to best solve economic issues in the US are also at play. President Donald Trump’s tariffs, levied against goods from dozens of countries, have divided some rank-and-file union members who have historically advocated against free trade agreements

Unions, like the United Auto Workers, with a mix of more left-leaning public sector workers and more culturally conservative private sector workers, have struggled to maintain a consistent message to organize members, Masters said.

“Over the issue of tariffs, they’re divided, but also in terms of overall ideology,” Masters said. These unions “have divisions between those sectors on certain policy issues, whether it’s the Gaza-Israeli war or certain cultural policies pertaining to equality in the workplace.”

Political Climate

The NLRB’s lack of a quorum for much of 2025 and the upheaval of the federal workforce have also dragged down organizing, labor attorneys said.

Since taking office, Trump has sought to end collective bargaining rights for over 1 million federal workers, citing national security concerns. That move, combined with the administration’s mass-firing of federal employees, has taken a toll on the most highly organized sector of the US economy.

“When you don’t have a functioning NLRB, union activity goes down. When immigrant workers are afraid, union activity goes down,” said Kate Bronfenbrenner, director of labor education research at Cornell University. “It’s hard to organize when people are afraid to talk.”

According to the BLS 2024 survey, about 32.2% of public sector workers were union members, five times the rate of the private sector.

Despite a difficult 2025, some stakeholders said the NLRB’s restored quorum could lead to an uptick in organizing activity in 2026. However, with the board’s Republican-majority that is likely to be more business friendly, unions might start to focus on organizing smaller workplaces that are less likely to litigate, said Meredith Kirshenbaum, a principal at Goldberg Kohn.

A $5 million proposed cut to the agency’s budget—coupled with the the NLRB’s case backlog—could also create challenges for unions going forward.

“Not that $5 million is such a big number, but I think any effort that impacts the capacity of the board is going to create potentially more backlog,” Kirshenbaum said. “If it takes a year or two years to get an unfair labor practice charge resolved, then I think unions are going to be less interested in pursuing the administrative process.”

To contact the reporter on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.