Unions have been uncharacteristically slow to stage traditional, wide-ranging workplace strikes amid the snowballing health and economic crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. But that lack of formal action appears about to change.

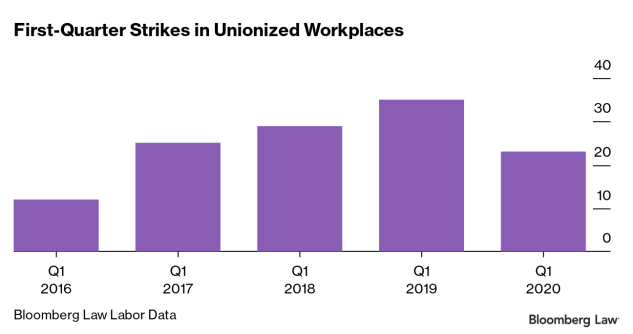

According to Bloomberg Law’s database of work stoppages, unionized U.S. workplaces saw 23 strikes in first quarter 2020, idling just 16,829 workers. These are the lowest first-quarter totals in four years.

Labor leadership was certainly busy in the early weeks of the outbreak, but its role mostly revolved around supporting and promoting workplace protests that have sprung up organically by employees required to remain on ...

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.