Since January 2025, the Trump Administration has raised tariffs on US imports to their highest average levels in recent history, from a universal 10% tariff on virtually all goods imported into the US to a threatened 145% on goods imported from China and varying levels of “reciprocal” tariffs on dozens of additional countries (“Trump Tariffs 2.0"). These tariffs include 25% tariffs on products deemed noncompliant by the administration with the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) update to the North American Free Trade Agreement and 25% tariffs on steel, aluminum, and auto-related products. Other planned tariffs include pharmaceuticals, copper and copper derivatives, semiconductors, and timber and lumber. Further, the US faces retaliatory tariffs from several countries and the European Union.

Aside from the immensity of the Trump Tariffs 2.0, the manner in which they have been threatened, imposed, paused, and increased has paralyzed companies into inaction. The proposed tariffs have been changed over 60 times since January. Companies anticipate that the Trump Tariffs 2.0 will be disruptive to business operations, and they can calculate outcomes based on different scenarios, but few actions can be taken until the tariffs are finalized.

One of the few areas where companies can address the tariffs before they are finalized is transfer pricing. Due to the close-knit interaction between transfer pricing and tariffs, companies can anticipate that tariffs of this magnitude will have a negative impact on transfer pricing compliance and a dysfunctional impact on tariff compliance. Therefore, companies would be well-advised to review their transfer pricing compliance, anticipate the impact of various levels of tariffs, review and potentially revise their intercompany contracts, and consider whether some portion of the impact of the tariff costs should be borne by a related party outside of the US.

The Interaction Between Tariffs and Transfer Pricing

A “tariff” is a tax on imported goods overseen by the US Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”). The tariff rate varies depending on the particular class of goods to which it applies and its “country of origin” (“COO”). The imported goods are classified using the Harmonized Tariff System of the US (“HTS”). The COO to determine the applicable tariff refers not to the country of shipment or sale, but the country where the product was “substantially transformed” under CBP rules. The tariff cost generally becomes part of the inventoriable cost of the imported product; upon sale, the tariff cost will be reflected in the cost of goods sold (“COGS”) for the imported product.

The tariff rate is applied to the import valuation amount. The most common valuation methodology employed by importers is transaction value, “the price actually paid or payable for the merchandise when sold for exportation to the United States…" (19 U.S.C. §1401a(b)). An importer may not use the transaction value if the buyer and seller are related unless the importer demonstrates that the “circumstances of the sale” for the imported merchandise indicate that the relationship did not influence the price paid or payable (19 U.S.C. §1401a(b)(2)(B)). Despite the language of the statute, most imports between related parties use transaction value based upon the representation that the relationship did not influence the terms and conditions of the sale.

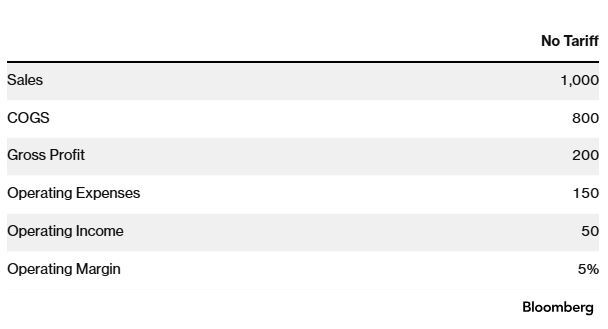

Example 1: Impact of Tariff

Alpert Associates (AA), a Mexican company, is wholly owned by Domer Distributors (DD), a US company. AA produces trumpets that are sold to DD using a transfer price of $800 (transaction value). DD provides evidence that the transaction value is similar to the price charged by a foreign-based company, Tijuana Tunes (TT) for similar goods, so the tariff will most likely be based on the transaction value of $800. After a 25% US tariff, the trumpets will be carried in the DD inventory at a value of $1,000 (125% x $800).

Although the tariff rules impose initial responsibility for payment of the tariff on the “importer of record” (usually a US distributor or manufacturer), the parties to the transaction are allowed to contractually allocate the tariff costs among the parties to the transaction. If the parties to any tariff cost allocation arrangement are related, any allocation arrangement must also satisfy the transfer pricing rules.

The tax rules regarding transfer pricing require taxpayers to achieve results on related party transactions within an arm’s length range of results established through a comparison to the results of similar transactions between similarly situated unrelated entities. A key aspect of any transfer pricing analysis is comparability, which involves an examination of various factors that affect prices or profits in arm’s length dealings. Treas. Reg. §1.482-1(d)(1) addresses comparability under the following broad factors: (a) functions, (b) contractual terms, (c) risks, (d) economic conditions, and (e) property or services.

The comparable profits method (“CPM”) with an operating margin (“OM”) profit level indicator is frequently employed to evaluate whether the transfer price on sales of tangible goods between a related manufacturer and distributor are arm’s length. This approach evaluates the arm’s length nature of the transfer price based upon whether the results of the distributor tested party fall within an arm’s length range of operating margin results of similarly-situated, unrelated distributors.

Example 2: Transfer Price Before Tariffs

DD reviewed the returns of similarly-situated musical instrument distributors (“comparables”) on unrelated purchases and found that the arm’s length range of operating margins of those comparables is between 4% and 6%. Therefore, DD benchmarked its operating margin return at 5%.

Impact of Tariffs on Transfer Pricing

Tariffs represent a significant cost to be included in inventory. Thus, tariffs will complicate two aspects of transfer pricing analysis, the comparables results, and the tested party distributor results. The impact of the tariffs on tested party distributor results may require a post-importation adjustment to the transfer price that could produce customs and tax compliance issues.

Tariffs apply to all importers, whether related to the manufacturer or not. New tariffs can materially alter comparability factors, including:

- The ability to pass the tariff cost on to customers through price increases;

- Changes to production costs at different locations;

- Access to alternative sources of supply; and

- Contractual obligations which may delay alternative arrangements.

The results of unrelated comparable companies form the benchmark for determining whether the related party transactions are arm’s length. The impact of tariffs on the results of comparable companies and the lack of detailed information regarding that impact creates reliability concerns with the application of transfer pricing methods for tangible goods.

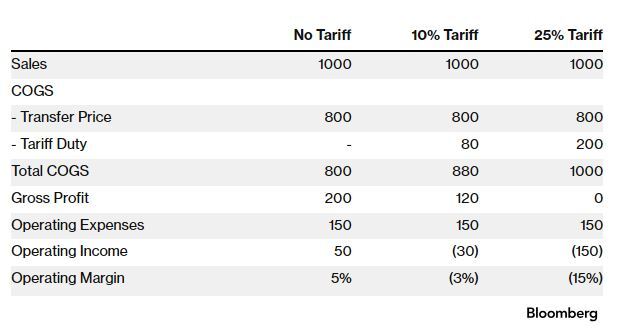

Taxpayers often apply the Comparable Profits Method with an operating margin profit level indicator to evaluate the transfer price. Example 3 demonstrates the impact of a tariff on the operating margin of the distributor if none of the tariff is shifted to the customer or to the manufacturer through a price change.

Example 3: Impact of Tariff on Profitability

Based on Example 2, the impact of the tariff on the results of the comparables might affect the benchmarked return that DD seeks to achieve. The impact of a 10% or 25% tariff on DD’s operating margin is reported in the below analysis.

With either a 10% or 25% tariff, the distributor finds itself incurring an operating loss. If the comparables produce an arm’s length range of 3% to 6% operating margin, an upward income adjustment would be required to bring the distributor’s results within the arm’s length range. This would be accomplished by a reduction to the transfer price.

If the taxpayer sets its customs valuation based upon its transfer pricing, a downward transfer pricing adjustment will trigger a post-importation downward customs valuation adjustment. Importers have at least two procedural options to report transfer pricing adjustments to CBP, the “Reconciliation Program” or a “prior disclosure” letter. Under the Reconciliation Program, the importer flags importation entries and declares an initial temporary value to be subsequently reconciled, no later than 21 months after importation. Importers may also make a voluntary “prior disclosure” to report a previously undeclared value or price adjustment in exchange for significantly mitigated customs penalties.

Under US transfer pricing rules, an upward transfer pricing adjustment to the income of a related party necessarily produces a downward adjustment to the income of the other related party, but the tax authority in the other involved country may not agree to the change. Under the US tax treaty network, a US taxpayer can request the assistance of the IRS to endeavor to achieve a downward adjustment to the income of the related party in a tax treaty country. This treaty mechanism, the “mutual agreement procedure” (“MAP”), allows treaty partners to eliminate double taxation arising from transfer pricing disputes. CBP requires satisfaction of certain tests under HQ W548314 to approve post-importation adjustments.

Other tax authorities could object to the reduced tax revenues caused by the self-enriching tariffs imposed by the US government. Shifting the cost of tariffs to related parties in other tax jurisdictions through transfer pricing mechanisms is likely to lead to some difficult discussions between tax authorities in bilateral negotiations between treaty partners in the MAP. Moreover, the US might raise similar objections with respect to any reciprocal tariff levied by the other country.

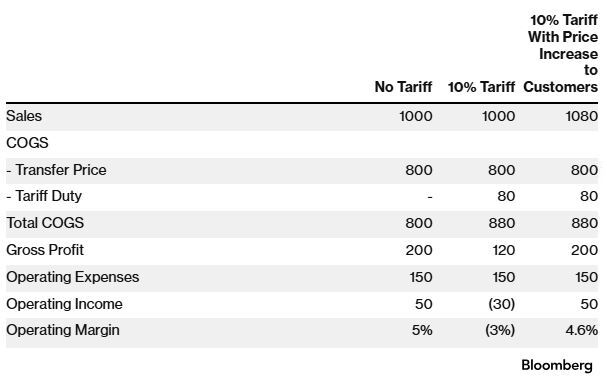

Some or all of the tariff costs can be passed through to customers in the form of a price increase. The ability to increase the price to customers is generally dependent on customer price sensitivity and the availability of substitute goods. It is important to note that even with the full passing of the tariff cost to customer, the net operating margin is lower than the pre-tariff scenario (5/100=5% vs. 5/108=4.6%), as illustrated in Example 4.

Example 4: Passing Tariff to Customers

If DD’s customers are very loyal to TT trumpets and will accept no substitute, DD might be able to pass some or all of the tariff costs to those customers in the form of a price increase.

Impact of Transfer Pricing on Tariffs Continued

As demonstrated above, Trump Tariffs 2.0 have the ability to undermine transfer pricing and customs compliance efforts. However, in some circumstances, the proactive application of transfer pricing policies can bolster transfer pricing and customs compliance and also reduce the actual amount of tariffs paid.

The payment of tariffs is initially the responsibility of the importer of record, but the impact of that tariff cost can be shared between parties. For example, if a US distributor pays the tariff on goods imported from a foreign manufacturer that is responsible for the tariff cost, the parties could affirmatively lower the import price to reflect that the goods are burdened with a tariff.

The regulations under §482 recognize that risk affects transfer prices, and those rules generally respect the ability of taxpayers to determine which party bears a particular risk, as long as the allocation is consistent with the economic substance of the transaction. An allocation of risk after the outcome of that risk is known or reasonably known lacks economic substance. In considering the economic substance, the following factors are relevant—

1. Whether the pattern of the controlled taxpayer‘s conduct over time is consistent with the purported allocation of risk between the controlled taxpayers; or where the pattern is changed, whether the relevant contractual arrangements have been modified accordingly;

2. Whether a controlled taxpayer has the financial capacity to fund losses that might be expected to occur as the result of the assumption of a risk, or whether, at arm’s length, another party to the controlled transaction would ultimately suffer the consequences of such losses; and

3. The extent to which each controlled taxpayer exercises managerial or operational control over the business activities that directly influence the amount of income or loss realized. In arm’s length dealings, parties ordinarily bear a greater share of those risks over which they have relatively more control.

Although the buyer and seller of imported goods may not have a contract in place that specifically allocates tariff costs between them, the actions of the parties and previous transfer pricing documentation may indicate the proper allocation of risks. Transfer pricing documentation may allocate most risks to one party, creating the expectation that party should also bear the risk of tariff costs. Further, the characterizations of the parties in transfer pricing documentation and benchmarked levels of income may indicate the appropriate allocation. For example, a benchmarked distributor’s profit between 2% and 5% would appear to be inconsistent with an expectation that the distributor would bear a 25% tariff.

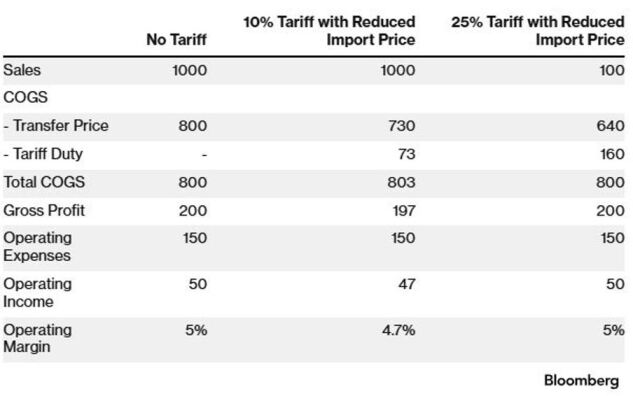

Assuming that DD, per Examples 2, 3, and 4, can support an allocation of the tariff costs to the non-US related party (AA), DD will need to compute the tariff impact and reduce the import price by an amount to achieve the transfer of tariff costs.

Although allocation of the tariff costs to the non-US entity does not avoid the tariff, it does reduce the import value, thus reducing the total amount of tariff cost. For example, if the import value without tariff is $800 and the tariff percentage is 25%, the import price should be reduced to a price at which the tariff cost plus the import price would generally leave the distributor with the same profit percentage as if there were no tariff. This is illustrated in Example 5.

Example 5: Reduce Transfer Price for Tariff

If DD can demonstrate that it is a low-risk distributor and cannot bear the tariff costs and earn an appropriate return if it bears the tariff, DD might be in a position to reduce the import price to maintain an appropriate operating margin for a distributor.

As shown in Example 5, the allocation of the tariffs costs to the manufacturer prevents the need for post-importation adjustments, thus eliminating the need for MAP and customs prior disclosure letter. Further, the reduction of the transfer price reduces the import value, thus reducing the amount of tariffs payable.

Takeaways

The Trump Tariffs 2.0 promise to be a disruptive force in global commerce. In addition to the immense impact on profitability and supply chain operations, these tariffs can be expected to undermine transfer pricing and tariff compliance efforts. However, a proactive application of transfer pricing policies and close monitoring of import transactions should contribute to effective transfer pricing and tariff compliance. In some circumstances, the proactive application of transfer pricing policies may reduce the amount of tariffs payable.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law, Bloomberg Tax, and Bloomberg Government, or its owners.

Author Information

Ken Milani is Professor of Accountancy Emeritus at the University of Notre Dame, Mendoza College of Business. Steven C. Wrappe is the National Transfer Pricing Technical Leader at Grant Thornton LLP and an adjunct professor at New York University School of Law and University of California-Irvine School of Law. Justin Grocock is a Transfer Pricing Manager at Grant Thornton Advisors LLC in Chicago, IL.

Grant Thornton LLP and GT Advisors (and their respective subsidiary entities) practice as an alternative practice structure in accordance with the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Code of Professional Conduct and applicable law, regulations, and professional standards. Grant Thornton LLP is a licensed independent CPA firm that provides attest services to its clients, and GT Advisors and its subsidiary entities provide tax and business consulting services to their clients. GT Advisors and its subsidiary entities are not licensed CPA firms.

Write for Us: Author Guidelines

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Soni Manickam at smanickam@bloombergindustry.com

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.