- Decision is the latest attack on the administrative state

- Judicial review will be the most affected by the ruling

- In Focus: Chevron, Loper & Agency Deference (Bloomberg Law subscription)

The US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn a decades-old judicial test on the scope of agency authority gives opponents a clearer legal path to challenge rules—and a fresh headache to regulators trying to defend them.

In a 6-3 decision handed down Friday, the justices eliminated a long-standing doctrine on regulators’ ability to interpret ambiguous laws.

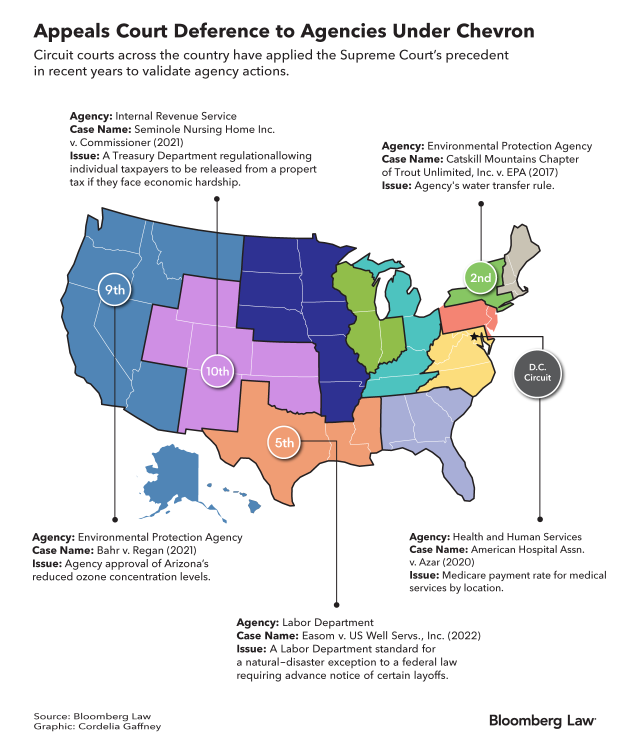

Under the doctrine—minted in the 1984 case Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council—courts deferred to an agency’s interpretation of ambiguous statutory authority if the agency’s definition was judged reasonable.

With that two-part test gone, the focus now shifts to lower courts, which will have to vet regulations without the precedent.

“Today’s decision will define how we think about challenges to government regulation for the next generation,” Alston & Bird partner Kevin Minoli said in a statement. “Today’s decision unquestionably means that more government regulations will be overturned by the courts.”

The opinion is the latest in a series of high court moves to curb government agencies, dealing another blow to the power and sweep of the administrative state.

The high court’s 2021 decision ending the Covid-era eviction moratorium is one such ruling that chips away at the power of the federal government, said Renée Landers, an administrative law professor at Suffolk University.

In that case, the justices said the executive branch ran afoul of the major questions doctrine, which it established in recent years to rein in significant agency actions.

Since 2021, the court has also applied that doctrine to doom the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s Covid vaccination rule, and the Education Department’s bid to forgive thousands of student loans.

The court is poised to issue a decision July 1, in Corner Post, Inc. v. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, on the length of time agency actions can be challenged under the Administrative Procedure Act.

“Ultimately, the court is making it virtually impossible for Congress or the agencies to address big problems,” Landers said. “I think we’re back in the New Deal era.”

REGISTER NOW: Webinar on what’s next for the future of the administrative state on July 8 at 1 p.m. Eastern.

‘Sea Change’

The decision is likely to spur a fresh wave of litigation in lower courts against agency rulemaking, brought by challengers who now have an added advantage.

Lawsuits challenging agency actions climbed last year, in the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent major questions rulings, Bloomberg Law data show.

Some industry and state challengers have long been critical of the Chevron doctrine’s use in the courtroom, particularly when fighting against rules for which they believe regulators took too much liberty in interpreting congressional intent.

The impact of eliminating Chevron for challenges to new regulations is lessened after years of Supreme Court skepticism making the precedent less significant, and also because judicial review of agency action has already grown more searching following the recent advancement of the major questions doctrine, said Christopher Walker, an administrative law professor at the University of Michigan.

Still, rolling Chevron deference back altogether “takes an argument out of the quiver of agency lawyers and puts new arguments in the quiver” for industry challengers, said Nathan Richardson, a professor at Jacksonville University College of Law.

The decision “takes the gloves off” by eliminating judicial deference of ambiguous laws, which may reduce the amount of consistency in rulings across courts, make a difference in close cases, and lead to the government losing some cases they previously wouldn’t have, said Jeffrey Lubbers, an administrative law scholar at American University.

While eliminating Chevron will make a meaningful difference in some cases, that change on its own won’t trigger a major upheaval in court review of agency actions, Lubbers said. The major questions doctrine “already relegated Chevron to minor questions,” he said.

“But when you add this to all the other cases, it’s been a sea change in administrative law, putting a dampener on government’s ability to protect citizens from health, safety, environmental, and consumer threats,” Lubbers said. “This decision is a capstone to that whole series of rulings.”

Even with the upheaval of agency deference moving forward, the Supreme Court said the ruling does “not call into question prior cases that relied on the Chevron framework.” This means that, though agencies will face a wave of tougher litigation, it won’t swell with cases looking to retroactively challenge standing rules.

Slower Change?

The decision may force agencies to be more cautious in writing regulations, especially when they’re acting under ambiguous laws.

Agencies such as the EPA and the Department of Health and Human Services are regulated under decades-old statutes that are rarely amended or are loosely worded regarding technical and scientific issues.

Regulators may spend less time explaining why they think they have the authority to issue a particular regulation, said William Buzbee, an administrative law professor at Georgetown University.

“Chevron gave agencies an incentive to explain themselves,” Buzbee said. “One thing we might see is less agency explanation of why they read a statute to say they can regulate, and a lot more quoting of the statute.”

Agencies are likely to move more slowly to try to better insulate rules from court challenges, according to James Goodwin, a senior policy analyst at the Center for Progressive Reform.

“They’re going to spend a lot more time writing the rules with one audience in mind: and that’s a judiciary that feels empowered to second guess policy decisions,” Goodwin said.

This could mean weaker rules and longer timelines, he noted, on top of the regulatory hurdle the high court has erected with its major questions doctrine.

The US Labor Department preemptively moved away from relying on the doctrine while defending legal challenges to regulations.

The ruling may make agencies more cautious, but it won’t completely change how they do business, according to Jonathan Siegel, administrative law professor at George Washington University.

The high court said that lower courts can’t make agency interpretation “binding,” but does signal support for courts to “respect” executive views when sussing out an informed decision.

“I don’t anticipate some cataclysmic night-and-day change in what agencies do,” Siegel said. “What I would anticipate is that agencies will more frequently get overturned.”

The case is Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, U.S., No. 22-451, Decision 6/28/24.

To contact the reporters on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.